Video & Transcript of biologist Jeremy Griffith

talking with primatologist David Chivers

via Skype on 10 October 2014

Jeremy Griffith: My name is Jeremy Griffith. I’m an Australian biologist and the author of IS IT TO BE Terminal Alienation or Transformation For The Human Race? (IS IT TO BE was a special edition of FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition, that was released especially for scientists.) I’m talking to Dr David Chivers, a primatologist at Cambridge University and a former president of the Primate Society of Great Britain.

David, you study gibbons and other forest primates, so do you describe yourself as a primatologist or a physical anthropologist, I’m not quite sure?

David Chivers: No, it’s difficult isn’t it. Physical anthropology has changed to biological anthropology and I focus mainly on primates but I’m almost a wildlife biologist involved in ecology, behaviour and conservation, focusing on the Asian apes.

Jeremy Griffith: You spent many years in South East Asia, India, Bangladesh, Brazil. That must have been an amazing time.

David Chivers: Oh, it’s been wonderful. My first two years in the Malay Peninsula were the most intensive as I was doing my doctoral field work. From 1970 to 1985 I organised students in Malaysia and I’d go and visit them for a few weeks each year. We shifted to Indonesia in 1985, working in the centre of Borneo to try and understand the role of fruit-eating animals in seed dispersal and the natural regeneration of forests and there was a unique population of hybrid Gibbons that were the main focus of our study. I then had students in India and Bangladesh that I went to visit and then in South America. Now we’re essentially based in Cambridge but go into the field to advise these doctoral students.

Jeremy Griffith: I’ve seen some very funny footage on YouTube of you imitating the gibbons in the forest where they make their territorial cry that’s so typical of that region and I know you’re famous for it. I won’t ask you to do it now David but it’s amazing to hear you do it! (People can go to www.youtube.com/watch?v=o8nxf-0n9Z4 to watch it.)

Okay, so David’s familiar with my work and he said about this book IS IT TO BE, as he’s said previously about my work, that ‘the sequence of discussion is so logical and sensible, providing the necessary breakthrough in this critical issue of needing to understand ourselves.’ So that’s a wonderful endorsement. David is both familiar with and empathetic with my work but he has expressed concern about the extremely confronting nature of some of the concepts, so that’s what I thought would be particularly helpful to discuss with him today.

Just to identify what those concepts are, David emailed me the other day saying, ‘When I mentioned your explanation for autism to my wife, she said, as do many authorities, that it is a genetic defect, that everyone is desperate to be a good mother.’ So yes, we’ve attributed problems like autism and even Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), those sort of mental illnesses which are in epidemic proportion in our society at the moment, to damaged genes and so forth, and even chemicals. My book says that there’s a deeper psychological reason for these afflictions, which is that they are due to humans’ inability, these days, to adequately nurture their offspring, and that’s a very confronting truth for parents. It’s just one of the examples of the many ideas in my book that people find difficult to tolerate. Alvin Toffler, in his 1970 book Future Shock, spoke of the ‘the shattering stress and disorientation that we induce in individuals by subjecting them to too much change in too short a time’ (p.4 of 505) and I suggest that when he was writing this concept of ‘future shock’ he was anticipating a time in the future when there would be such a paradigm shift, such a massive breakthrough in understanding of ourselves that it would bring about a complete change in our understanding. The old understandings would be made transparent and the new understandings would be a shock, even though they’re transformative, and that’s exactly what happens when understanding of the human condition, which is the deepest underlying issue in all human affairs, is finally explained—it brings a massive change.

When the blinds are drawn, as it were, and the true explanation of ourselves is finally revealed, while that truth is dignifying and redeeming and healing, or ameliorating and reconciling, it can’t help but also be revealing of all the dishonest denials we’ve had to use while we lacked that explanation.

Plato is considered one of the greatest philosophers in history and his most famous work is called The Republic and at the centre of The Republic is this allegory of a cave where he describes humans as living deep underground. They’re in fear of the sun outside and its representation, namely the truth. They can only see the world in shadows, aberrations of the real world. When you bore down into that, the truth is that we haven’t been able to face this issue of the human condition. We’re unable to understand why we humans have been so competitive, aggressive and selfish when clearly the ideals of life are to be the opposite, to be cooperative, loving and selfless. We had no choice but to hide from that truth.

Plato described what a shock it would be for the human race one day when we found sufficient knowledge to finally explain that great riddle of why we are the way we are, why we’re less than ideally behaved, explain the human condition, enabling us to leave the cave. He said that we’re all going to be in such shock we’ll hardly be able to face the sun for a long time because the brightness of it will be so overwhelming.

That’s the situation that’s finally emerged—through the advances made in science we can now finally explain, in first-principal biological terms this issue of the human condition, which is the core concept presented in chapter 2 of my book. But again, it brings about ‘future shock’, too much to try and adjust to. When the blinds are drawn and the truth revealed as it were, unavoidably, all the lies, all our dishonesty, all our denials, all the excuses that we’ve been using are suddenly rendered transparent and no longer effective. So, this is exposure day, or truth day, or transparency day, or what’s historically been referred to as ‘judgment day’, which is not actually a time when we’ll be condemned, but a time of understanding. Nevertheless, it is also a time of immense transparency and revelation of who we really are. While the human condition is defended, it’s also exposed. So, that’s unavoidable. But it’s essentially this incredibly serious problem that has emerged that I want to talk to David about.

So, David, if you’ll bear with me for a second I’ll just try to context this book a little bit.

To try and explain the title of my book IS IT TO BE Terminal Alienation or Transformation For The Human Race?, on the back cover is a quote from Professor Harry Prosen, the former president of the Canadian Psychiatric Association who has written the Introduction to the book. He says:

‘Is it to be, or not to be? [which plays on probably the most famous phrase in English literature from Shakespeare’s Hamlet] That is the question: are we going to make it—is the human race going to find the redeeming and transforming understanding of our ‘good and evil’-afflicted human condition—or is our species headed for terminal psychosis and alienation? Humankind is in the balance: will it be self-destruction or self-discovery?’

That’s the crisis point we’ve arrived at, and then Professor Prosen goes on to say:

‘Well, astonishing as it is, this book presents the 11th hour breakthrough biological explanation of the human condition needed for the psychological rehabilitation and maturation of the human race! It takes humanity from a state of bewilderment about the nature of human behavior and existence to a state of profound understanding of our lives. It is a case of having got all the truth up in one go—understanding has finally emerged to drain away all the pain, suffering, confusion and conflict from the world. This is it—THE BOOK THAT SAVES THE WORLD!’

That’s a very bold statement about the importance he sees in this book but what I’m wanting to talk with David about for the benefit of all readers of my book is how to cope with that enormous change. David has focused on one of the key concepts that people will find difficult to accept, which is that lack of love is what causes autism. The traditional excuse is that it’s due to genetic defects and we can obviously see that such an excuse would be very relieving for parents. As a quote I mention in my book says, ‘The biggest crime you can commit in our society is to be a failure as a parent and people would rather admit to being an axe murderer than being a bad father or mother’ (‘A Single Mum’s Guide to Raising Boys’, Sunday Life, The Sun-Herald, 7 Jul. 2002). That pretty well captures the problem. Parents would rather admit to being an axe murderer than being a bad parent. We’ve been very insecure about this idea that lack of nurturing or love is the reason for the epidemics we’ve got in the world at the moment of ADHD and, in the extreme, autism, extreme dissociative behaviour.

That’s the context of what I wanted to talk about. Does that all tally with you, David?

David Chivers: Yes, I guess so. It’s just that the problem of wanting to be good parents, and many of them try, they think they are being good parents but they can’t because of some genetic disorder in their offspring. I agree with so much of what you have said and presented but this does sort of stick out.

Jeremy Griffith: If it’s alright David, I think the best way to answer this is to introduce the explanation of the human condition that I give in this book. So if you can just bear with me I’ll explain that.

I should begin by saying that historically we’ve used the excuse that humans are competitive, aggressive and selfish because of our animal heritage, that we are ‘red in tooth and claw’, as Lord Alfred Tennyson put it (In Memoriam, 1850)—that we have savage animal instincts that make us fight and compete for food, shelter, territory and a mate. But this can’t be the real cause of our divisive behaviour because descriptions of our human behaviour such as egocentric, arrogant, deluded, optimistic, pessimistic, artificial, hateful, mean, immoral, guilty, evil, depressed, inspired, psychotic, alienated, all recognise the involvement of our species’ unique fully conscious thinking mind. There is a psychological dimension to our behaviour. We have suffered not from the genetic-opportunism-based, non-psychological animal condition, but from the conscious-mind-based, psychologically distressed human condition. To argue that we are competitive because of a territorial imperative overlooks the fact that we are conscious, that we suffer from a psychological condition. Such excuses sustained us, got us ‘off the hook’, as it were, but one day we had to find the deeper psychological reason for our particular human condition.

That is the key presentation explained in this book and it’s been the holy grail of the whole of biology to one day finally be able to explain ‘us’—human behaviour—where is the divisiveness in us, our capacity for atrocities and inhumanity, coming from? Chapter 2 answers that key question and to quote Professor Prosen, ‘reading Chapter 2 is a transformative experience’. (Note, chapter 2 is now chapter 3 of FREEDOM.)

I’m going to now explain as simply and quickly as I can the biological explanation presented in my book for the psychologically distressed, upset state of the human condition.

Humans have an original instinctive self. In the story of the Garden of Eden in Genesis in the Bible, it says that Adam and Eve took the fruit from the tree of knowledge, presumably meaning they became conscious. Then it says that they became sufferers of ‘evil’, which is the old term for competitiveness, egocentricity, anger, alienation and so forth, and as a result of that were banished, thrown out of the Garden of Eden.

Now, what my book says is that yes, we did become conscious, and as a result of that, inevitably, a clash emerged with our already established instinctive self. That clash was unavoidable and so this is a dignifying explanation of why we became upset. Finding that explanation allows the upset to subside.

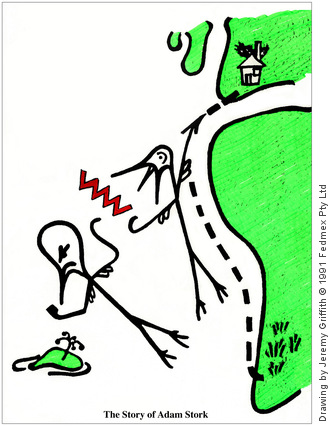

To use a simple analogy, we all know that birds are instinctively orientated to a flight path. For example, storks migrate around Africa up to their summer breeding grounds on the rooftops of Europe and then back again. Obviously, they have acquired that perfect orientation through natural selection—the storks that were genetically inclined to fly across the Sahara might have all frizzled and so they’ve acquired the perfect path to follow so that they can survive; it’s an instinctive orientation. But let’s imagine we were to put a fully conscious mind on the head of one of these storks. We’ll call him Adam Stork because this story parallels with the story of Adam and Eve, although it has a different ending. So now we jump in an ultralight plane and we follow this stork on his annual migration north and we watch what happens, how the equivalent of the human condition emerges.

So, we’re watching old Adam Stork, he’s flying along and he now has a fully conscious thinking mind that can understand cause and effect, make sense of experience. But he’s also got an instinctive self which tells him where to fly and where not to fly. He’s flapping along and he starts thinking for himself, ‘Look, there’s an apple tree down there. I’ll think I’ll go down and have a feed of apples, why not?’ At this point he has no explanation of why he shouldn’t carry out experiments in understanding cause and effect. So he duly carries out this experiment and flies off towards the island. Obviously, his instinctive flight path doesn’t go down to the island so his instincts will try and pull him back on course.

At that point he’s in a dilemma. Does he persevere with his search for knowledge or just obey his instincts? We can see him veer off to the left, hesitate and then fly back on course. He’s encountered this criticism, in effect, from his instincts that don’t want him to fly to the island and he thinks, ‘Oh no, I’ll obey them and fly back.’

He continues flying along on course until he sees another island, and this time he thinks, ‘Why not fly down to that island and have a rest?’ There’s no reason why he should or shouldn’t at this stage, he hasn’t acquired any knowledge and the only way he’s going to learn what are good ideas and bad ideas is to carry out experiments in self management.

So, again he flies off course—we see him deviate, then we see him hesitate because his instinctive self starts to, in effect, pull him back on course again. Now, this time he realises he can’t deny his intellect. Sooner or later he must find the courage to master his conscious mind by carrying out experiments in understanding. He decides, ‘This time I’m going to defy my instincts and persevere with my search for knowledge and head down towards the island.’ He doesn’t acquiesce to his instincts and they are, therefore, going to, in effect, criticise him more and more.

Our instincts tell us when we need food or a drink of water and we can consciously override that need if we choose—our conscious mind has the power to either defy our instincts or go along with them. In this case, Adam Stork has decided that he must defy his instincts in order to keep searching for knowledge and is going to have to live with the criticism emanating from his instinctive self. Ideally, at that moment he would sit down on a limb and have a little talk, as it were, with his instinctive self and say, ‘Listen, you might be perfectly instinctively orientated to where we should and shouldn’t fly but you don’t understand why we should or shouldn’t fly in such and such a direction. I’m now using my conscious mind which is an understanding system so I need knowledge about why we should fly this way and not that way. By all means, tell me when I’m off course but don’t criticise me. You’re a gene-based learning system, you acquired your orientations through natural selection. I’m a conscious nerve-based learning system and I can understand cause and effect, so we’re two different learning systems.’

Now, that little explanation depended on Adam having knowledge about nerves and genes and the different ways they process information—one being an insightful learning system and the other being an instinctual system. But he had no knowledge or ability to explain anything. It was a catch-22 situation for the fledgling thinker, because to explain and defend himself he needed the very understanding he was setting out to find—specifically, explanation of the way genes and nerves process information. So what can old Adam Stork do? In paragraph 140 of IS IT TO BE (now paragraph 251 of FREEDOM) there is a cartoon illustrating the dilemma Adam Stork is in and the implications of having to live with such criticism. In this cartoon you can see him flying off course and you can see his instinctive self with a small brain on the right.

You can see that Adam, unavoidably, can only do three things because he can’t live all day, everyday with this unfair criticism which he can’t refute, because he can’t explain why he needs to search for knowledge.

Firstly, he becomes angry towards the criticism because he needs to express some resentment if he’s going to cope, we can’t expect him not to.

Secondly, he becomes egocentric. The Concise Oxford Dictionary defines ‘ego’ as ‘the conscious thinking self’ (5th edn, 1964), so Adam’s conscious thinking self is going to become centred or focussed on trying to validate himself, searching for a win in any situation, some form of relief from the unfair criticism he’s having to live with.

And thirdly, he blocks out the criticism. He says, ‘I don’t deserve it, I can’t explain why I don’t deserve it so I’m just going to block it out and live in denial.’ So he blocks out the criticism, becoming alienated from his instinctive self.

So, old Adam Stork has become angry, egocentric and alienated as the only responses available to this unfair criticism—in a word, he became ‘upset’, which replaces the condemning words ‘bad’ or ‘evil’ which are not deserved. The only way that he can end this unavoidable blocking out, retaliation and incessant search for reinforcement is to finally be able to explain himself. As I said, if he’d been able to explain himself on Day One of this search for knowledge he would never have become upset! And clearly, when he can explain the situation, all his upsets can subside.

Now, if we sit back and think about that—remember in the story of Genesis in the Bible, Adam and Eve took the fruit from the tree of knowledge, they became upset humans and they were ‘banished…from the Garden of Eden’ (Bible, Gen. 3:23). The Adam Stork story explains that they couldn’t avoid becoming upset, they had to have some way of relieving themselves of the unfair criticism. Adam Stork is, in fact, a hero because at any time he could acquiesce and give in to his instincts and fly back on course, but then he would never find knowledge. He has to have the courage to search for knowledge and suffer becoming angry, egocentric and alienated. As the marvellous musical The Man of Le Mancha says, we had to be prepared ‘to march into hell for a heavenly cause’ (Joe Darion, The Impossible Dream, 1965). Imbued in that description is the whole dilemma and paradox of the human situation; we had ‘to march into hell’—suffer becoming upset—‘for a heavenly cause’—which is to find knowledge.

My book presents the dignifying, redeeming, ameliorating, healing and transforming understanding of why we became upset. Overall, it was a terrible predicament in which we became psychologically upset sufferers of psychosis and neurosis. The Penguin Dictionary of Psychology’s entry for ‘psyche’ reads: ‘The oldest and most general use of this term is by the early Greeks, who envisioned the psyche as the soul or the very essence of life’ (1985 edn). We developed a ‘psychosis’ or ‘soul-illness’, and a ‘neurosis’ or neuron or nerve or ‘intellect-illness’. Our gene-based instinctive self or soul or psyche became repressed by our intellect for its unjust condemnation, and, for its part, our nerve or neuron-based intellect, our conscious mind became insecure, preoccupied with denying any implication that it was bad. We became psychotic and neurotic.

This is an explanation of our corrupted human condition, in biblical terms, our ‘fall from grace’. It explains that Adam Stork is actually a hero, not a villain and that he had to have the courage to defy his instincts and persevere with the search for knowledge. We are all sufferers of this human condition and since our fully conscious mind emerged some two million years ago, our upset has been increasing. We began by challenging our instincts which led to this clash between our instincts and our intellect and we went on this horrendous journey away from ourselves—we had to lose ourselves to find ourselves. Now that we can finally source and understand where all this began, all our upset can subside.

So that’s the macro presentation in chapter 2 of my book (now chapter 3 of FREEDOM), the dignifying explanation of our upset state. And there’s a lot more subtlety to it, for example, what were humans instinctively orientated towards? Obviously we’re not storks, we’re not orientated to a flight path. In chapter 3 (now chapter 5) I look at the anthropological evidence that shows what our ape ancestors were like some five million years ago, similar to what the bonobos (Pan paniscus), our closest living relatives, are like now. In chapters 4 and 5 (now chapter 5 and chapter 6) I reveal that nurturing is what made us human, that we acquired an orientation to being cooperative, loving and selfless through the development of nurturing. I explain that bonobos are nurturing of their infants, they’re a matriarchal, female-role-led society and they’re bringing their competitive animal condition under control through selecting for more cooperative males to mate with. So they are a living example of how we acquired our moral instincts, which has been one of the great mysteries.

The greatest mystery in biology and in science as a whole has been the issue of the human condition. One of the other huge mysteries has been how humans acquired their altruistic, selfless, loving, moral nature, the voice of which is our conscience. Nearly every science journal you pick up will have another theory about how we acquired our moral nature but in chapters 4 and 5 of my book (now chapters 5 and 6) you will see that it was through nurturing, through the loving of our infants. In fact, that idea was first put forward by a fellow called John Fiske, who you can read about it in chapter 5 of IS IT TO BE (now chapter 6), in 1874, only four years after Darwin put forward his idea of natural selection and it was described at the time as a theory far more important. Now, you have to ask, if John Fiske’s nurturing explanation for our moral nature was described as far more important than Darwin’s idea of natural selection and was presented four years after Darwin presented his book The Origin of Species, why haven’t we been taught that at school? And why have there been so many theories since which attempt to explain our altruistic moral nature without attributing it to nurturing?

So now we’re getting close to talking about David’s issue regarding autism, blaming it on a genetic defect rather than on bad parenting, or inadequate parenting I should say, because it isn’t actually ‘bad’, as I’ll now go onto explain.

We originally described that the centrepiece of all Plato’s writing was his allegory of humans having to live hiding underground because they can’t face the truth of the human condition. And because we have had to live in denial of the human condition, we’ve needed all these false excuses to get us by until we found the real defence for our upset state. For example, we used the excuse that we have animal instincts that need to compete for food, shelter, territory and a mate. Clearly, we suffer from a psychological human condition, not a genetic opportunistic animal condition but underlying all human behaviour is a huge insecurity about the key issue or question of why we haven’t been ideal. If we once lived in the proverbial Garden of Eden and our instinctive orientation is to be loving and cooperative, and that was acquired through nurturing, as evidenced by the bonobos, why did we ‘fall from grace’? Why did we fall out of that idyllic, cooperative, gentle, loving place? Humans now live deep underground in Plato’s cave of denial, a hideout where we can only see distorted images created on the wall of the cave by the flickering flames of the fire. We’ve had a distorted view of the world and one of those key distortions is to blame our divisiveness on our genes, on having aggressive, territorial animal instincts when again, we suffer from a psychological human condition.

Living in denial has been incredibly important to our survival. If what I’m suggesting is true, that our psychologically upset state emerged from a clash between our original instinctive self and our emerging consciousness some two million years ago, we’ve accumulated a lot of anger, egocentricity and alienation in those two million years! We are deeply, deeply, psychotic and neurotic, deeply repressing our instinctive ‘child within’ or ‘collective unconscious’, however we’d like to refer to it.

It’s been a diabolically awful situation—to be living in this magic, cooperative, loving, instinctive state and suddenly having to become angry, egocentric and alienated. We set out in search of knowledge, we unavoidably tried to block out the criticism from our instincts—became alienated; we unavoidably retaliated—became angry; and we unavoidably focused on trying to validate ourselves—became egocentric, and these are all divisive traits. Adam Stork was only criticised for deviating from a flight path. In our case, it was a terrible situation because our retaliation, defensiveness and desperation for reinforcement were at odds with our instinctive orientation to live cooperatively which produced even more criticism from our moral instincts. So that really upset us. After only a few hours of this criticism we are going to become very, very frustrated and deeply upset. Imagine living with it for just one day let alone two million years!

Imagine if you lived in a village and everyone agreed that no one was to plant weeds. You go ahead and plant weeds despite this but you can’t explain why you’ve planted them. This is in violation of the whole village’s agreed strategy and you can’t explain why you’re doing it. So, as far as the whole village is concerned, you’re one bad dude. You’re actually not, but you can’t explain why you’re not, so you’re going to have to live with an immense sense of criticism and condemnation. I mean, the villagers are going to be putting dead cats in your letter box after the first week, they’re going to turn their backs to you when you walk down the street, it’s going to be awful!

Humans have got a double whammy where our instinctive orientation was to an idyllic, integrative state acquired through a long nurturing period, similar to what the bonobos are in the midst of developing. Our instincts are to be loving and cooperative and we come into the world expecting it to be like that because our ancestors lived like that for ten million years prior to the human condition emerging. We’ve only been living in this psychologically upset state since the conscious mind fully developed some two million years ago, and only really intensely in the last 10,000 years with the advent of agriculture and the domestication of animals with humans living largely on top of each other which greatly magnifies the frustrations arising from this upset state of the human condition.

We come into the world still expecting it to be loving, cooperative and gentle and it’s nothing like that. Humans come into the world in an innocent state and adults can’t explain to them why the world isn’t perfect. We couldn’t even afford to admit we were upset while we were unable to defend that upset state. So we live in deep denial, deep in Plato’s cave under the ground, unable to face any truth about ourselves—deeply psychotic, soul-repressed and deeply neurotic, committed to living in denial. We’re alienated and we can’t see our alienation—you can’t be blocking something out and be aware that you’re blocking it out, otherwise you haven’t blocked it out! So we come into the world expecting it to be ideal and it isn’t and no-one will even admit that it isn’t, or talk about it. Instead there is this huge denial, this world of falseness.

So, of course children die a million deaths. Samuel Beckett described how brief our soul’s life is when he wrote, ‘They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more’ (Waiting for Godot, 1955). So, we are born astride a grave, and the baby drops down this hole in the ground and just for an instant, before it disappears into the hole, just a little bit of light comes in and that’s all we experience of happiness and an ideal state. We are born ‘astride a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more’. It’s that brief and that’s understandable after living for two million years unjustly condemned and never able to redeem ourselves, explain why it was unjust. There is a horrific amount of upset in us. Sure, we’ve learnt to civilise it (when we say ‘civilise’, we mean we’re restraining it, we’ve learnt to bottle it up or contain it, it doesn’t mean we’ve eliminated it) but underneath there is this volcanic anger and distress inside humans, and it comes out in wars and sex and other situations.

Devices, such as religion, where we tried to manage our upset by transcending it and deferring to some form of idealism, only served to hide our psychosis. There was no possibility of fixing all the trauma in the world until such time as this deeper understanding was found. Patching it up, putting band aids on the problem with better forms of restraint or better laws or better forms of self-discipline or going to gurus that teach us to transcend and love ourselves are all artificial solutions. Ultimately, we needed the understanding of our psychosis, the source of all our pain to finally start unpacking it and dismantling it and loving ourselves. We needed brain food, not brain anaesthetic. We needed to dignify ourselves. We needed to be able to understand the pain in the brain, we needed relief from the criticism and frustration. We needed the great burden of guilt to be lifted from the shoulders of the human race and this explanation does it. That is why Professor Prosen has said ‘this is the book that saves the world’, because it brings love to the core issue of ourselves. As Sir Laurens van der Post, the most quoted author in my books once said, ‘True love is love of the difficult and unlovable’ (Journey Into Russia, 1964, p.145 of 319). We needed, as the Rolling Stones’ song says, to have ‘sympathy for the devil’ and as William Blake titled his book, ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’. That was the great destiny of the human race, to one day find the redeeming, reconciling explanation of these two parts of ourselves, as Carl Jung the psychoanalyst was forever saying, ‘wholeness for humans depends on the ability to own their own shadow’, to love the dark side of ourselves, to make sense of it.

A May 2013 TIME magazine article titled ‘The Me Me Me Generation’, reported that ‘the incidence of narcissistic personality disorder is nearly three times as high for people in their twenties as for the generation that’s now 65 or older’. It refers to the current generation as ‘millennials’, saying they are ‘80 million strong…[the] biggest age group in American history’. It goes on to explain that the problem is that this narcissism is due to lack of self-esteem, that this ‘me me me generation’ is extremely insecure. They lack the ability to love themselves. They are entering this end play state where they just can’t bear anymore criticism and they desperately, desperately want to be reinforced so they’re narcissistic, self-worth-obsessed.

If we just think again about Adam Stork flying off course and being criticised unfairly for it, and then we extrapolate that for some two million years to get to where we are today, then by Jingo, we are going to be incredibly insecure by now. The more Adam Stork searched for knowledge, the more angry, egocentric and alienated he became, the more the next generation had to grow up with parents that were angry, egocentric and alienated—nothing like their original instinctive state where they were cooperatively and lovingly behaved. So, they die a million deaths as children, they grow up and then the next generation suffers even more. They adopt more denial, more need for reinforcement, more anger and so on and so on, it continues to escalate.

The human race is entering end play where the human body can’t endure anymore psychosis and neurosis and our Earth can’t cope with any more of the effects of our anger, egocentricity and alienation. Everyone is ripping off the environment for as much wealth as they can accumulate, we build bigger houses and have bigger cars, we go from one sporting competition to the next. It’s down to a situation where humans just live for the next win and in between there is really nothing of meaning in our lives.

Just to give you an illustration of this end play state and how desperately we need understanding of our condition to bring love to the dark side of ourselves and make us whole. I’ve just returned from a trip to America and the UK and I visited someone in London who told me that at sports events in the UK now people are so angry and virulent that they boo and clap and shout out during traditional moments of silence when honouring the death of a club champion or the loss of a serviceman defending the country, or when the national anthem is played.

Another example is a documentary I watched on the plane coming home about modelling agencies that specialise in supplying men and women who are particularly ugly because advertisers know that the public now finds beauty too confronting and too condemning, which is just astonishing!

A May 2014 article in The Atlantic reported that even political correctness is not evasive enough of reality for people. There’s a new trend called ‘empathetic correctness’, where students at universities are ‘refusing to read texts that challenge their own personal comfort’. Some campuses are even ‘proposing that so called “trigger warnings” be placed on…material that might “trigger” discomfort for students’ so that students can read only portions of the book with which they are fully comfortable. The article goes on to quote George Orwell’s dire prediction of the society which bans books. People can’t cope with any truth now, any self-confrontation, we’re incredibly insecure. This ‘me, me, me generation’, this ‘80 million strong…biggest age group in American history’ are now all narcissistic, now desperate for reinforcement.

Professor Prosen received an initial response to my book from an American psychotherapist who wrote about ‘the growing number of clients he receives that report a sense of despair and apprehension, not just about their own lives, but about the future of our species’. Harry responded saying, ‘I absolutely agree with your comments about anxiety over the state of the world now vibrating through everyone including myself…the world is craving some real bravery and honesty and thank goodness IS IT TO BE delivers that.’ There is so much anger and social disintegration in the Muslim world now and the rest of the world isn’t far behind. It’s just disintegrating everywhere as Adam Stork becomes more and more embittered and generation after generation unavoidably suffer even more distress in their upbringing. The world is in a terminal state. So, my book is titled IS IT TO BE Terminal Alienation or Transformation for the Human Race? because that’s the balance, that’s the equation we’re in. We either find the transformative understanding of the human condition which finally dignifies humans and brings relief at the fundamental psychological level, or we face terminal alienation. It’s a psychotic, disintegrating state we are in when students don’t want to read anything that’s at all critical of them and people are so angry that they boo in the silences at sporting events.

David Chivers: I’ve been very impressed in recent months, years with sport occasions at how dignified people have been during the one or two minute silence. I have been pleasantly surprised at the behaviour.

Jeremy Griffith: Well, I don’t know what that person was referring to but that’s what I was told. I don’t know David, what your experience is?

David Chivers: I watch a lot of sport and I have been pleasantly surprised at the behaviour, I’m familiar with the frustration and the selfishness of people but they have rallied to behave sensibly on those occasions.

Jeremy Griffith: Well, that’s good news. I don’t know what experiences have occurred in England that prompted that comment, but it was made to me. I imagine, were we to Google it, we would find where it’s been described. [A quick internet search lists the following entry on Wikipedia that discusses this growing trend: ‘In recent years a trend has developed (particularly with Association football fans) to fill the traditional minute of silence with a minute’s applause. Psychologically this is seen by some to convey a fond celebration of the deceased rather than the traditional solemnity…It is frequently alleged that the predominant reason for the minute’s applause tending to replace the minute’s silence is out of fear that opposition fans will not respect the silence, and spend their time booing, jeering, or otherwise attempting to disrupt it; many silences have been cut short from the usual minute to thirty seconds or less for this reason’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moment_of_silence). The following is a news account of the ‘shameful’ practice: ‘At my football club (Cardiff City) the other day, the pre-match minute’s silence for Remembrance was ruined by a small minority of Leeds United fans who chanted. They were roundly booed by Cardiff fans afterwards for their shameful behaviour.’ (‘Why rugby has never been the self-proclaimed civilised sport it believes itself to be’, 13 Nov. 2014; see <www.wtmsources.com/211>) I haven’t read it in the literature, I was just told about it. What you’re saying doesn’t surprise me. You would think that people would be very reverent and respectful in those situations. But I do think the overall fragility of the world at the moment is pretty well apparent to everybody.

David Chivers: We’ve also discussed the use of the term ‘race’ and I’ve realised now you have it on the front page of IS IT TO BE where you’re really talking about the human species.

Jeremy Griffith: Yes, but that is just a colloquialism. It’s just the phrase that everyone uses, ‘the human race’. David is pointing out that where I’ve used the term ‘race’ in IS IT TO BE I should have put inverted commas around it. I have made that change since David pointed it out to me and clarified that by ‘race’ I mean a group of people who have spent a long time together and are genetically closely related.

David Chivers: As a biologist I’ve been trained to recognise a ‘race’ as a very distinctive division of a species. And there are five races within the human species that we recognise and so to relate it to, and use the term ‘race’ for cultures and bigger groups is false.

Jeremy Griffith: Yes, but if a group of people do spend a long time together and go through a similar experience together, those experiences will be reflected in general in them as a group.

David Chivers: Yes, for sure, I agree totally, and there are ethnic groups, there are religious group, whatever, but they’re not a ‘race’.

Jeremy Griffith: Yes, I accept that. This is only an advanced copy and I’ve made that clarification in there now David, how I use the term ‘race’ is now qualified in there and wherever it’s mentioned it’s got inverted commas around it.

David Chivers: But we’ve still got the front page I suddenly realised.

Jeremy Griffith: Yes, I suppose it should be ‘human species’, but I think people would accept ‘human race’ as just a colloquial term that everyone uses.

David Chivers: But that’s dangerous, as you say, it’s colloquial and it’s dangerous. You do want to be really clear and concise in your presentation.

Jeremy Griffith: We should replace it with ‘species’ in that sense but I think you could argue David, that human race is a ‘race’ in the true sense that the whole of the human species at the moment is a ‘race’. In your definition of what a ‘race’ is, you said there were five specific races but as a collective whole they are a distinct entity so I think you can talk about the human race as a whole being a ‘race’, I think that’s not incorrect.

David Chivers: I can’t because you have the terms of hierarchy of the difference, you have species, you have sub species and so on. So, to call a species a ‘race’ to me is wrong!

Jeremy Griffith: Well okay, I think technically you’re right, it is wrong, but as a description, as a way of referring to the human race as a group, as a collective group, an identifiable, separable group of organisms, then I think the word ‘race’ in that sense is legitimate. But I understand what you’re saying and I’ve made those corrections.

David Chivers: You’re trying to use it at a different level, the same term but, you know, a group of bushman or a society of a particular national country and so you build it up in different religious groups and to use ‘race’ in such a variable way loses the rigour that I thought you were aspiring to.

Jeremy Griffith: Yes, I put that change in throughout the book. I put in ethnic group, I put quotes around it and I’ve clarified what is meant by it. I did all those things you asked.

David Chivers: I appreciate that but then I suddenly noticed it on the front cover, I didn’t realise that before. I mean it undermines and weakens your argument to use a term in such a variable way.

Jeremy Griffith: Yes, it wants to be rigorous. When I’m going out into this whole forbidden realm of the human condition, it’s so upsetting for people to have all this dug up and revealed, pulled up out of the cave as Plato said [see Video/Freedom Essay 11 on Plato’s cave allegory]. When they’re dragged out of the cave they are going to resist so we want to be as rigorous and as free of flaws as we can possibly be and I’ve tried to do that with the book. It’s very comprehensive, it does present all the different biological arguments for everything and gives them air time and describes them and tries to deal with them all. I try to be as fair and as comprehensive as I can be. And I have gone back and made that clarification in there.

David Chivers: Yes.

Jeremy Griffith: Okay just to bring this around. There are lots of heresies in IS IT TO BE because again, we’ve had to live in this cave of denial with all these contrived excuses which we’ve needed in order to cope. We blamed our human condition on being aggressive and competitive because of needing to compete for territory and so forth, when we actually have a cooperative, loving history and so on. We’ve got all these different false or contrived excuses that we’ve had to employ because we had to have some way of defending ourselves. Old Adam Stork has to block out that criticism somehow, he can’t live in that state undefended.

We needed all these devices and now they’re suddenly exposed as being false, superficial and artificial. And that exposure brings about a ‘future shock’, metaphorically referred to as ‘judgment day’, when suddenly all our dishonesties, artificialities, superficialities and, above all, our alienation is exposed.

The Scottish physiatrist R.D. Laing was so honest and he spoke of how ‘our alienation goes to the roots’. After two million years of living in denial, this is how deeply psychotic and neurotic we are—how alienated from our true self or soul: ‘Our alienation goes to the roots. The realization of this is the essential springboard for any serious reflection on any aspect of present inter-human life…’[p.12 of 156]. Laing is saying that we need to acknowledge that we’re psychotic in order to make any real progress and that’s why I’m criticising these biological excuses that have been used. They are not admitting this alienated state, they are living in denial of that. Laing goes on: ‘…the ordinary person is a shrivelled, desiccated fragment of what a person can be [p.22] …The condition of alienation, of being asleep, of being unconscious, of being out of one’s mind, is the condition of the normal man [p.24] …between us and It [our true selves or soul] there is a veil which is more like fifty feet of solid concrete…The outer divorced from any illumination from the inner is in a state of darkness’ [p.116]. So, we are living in a state of darkness which equates perfectly with Plato’s allegory of people living in a blocked-out, hidden, cave-like state. ‘We are in an age of darkness. The state of outer darkness is a state of sin–i.e. alienation or estrangement from the inner light’ [p.116]. We block out the inner light, the soulful, truthful condemning part of ourselves. ‘We are bemused and crazed creatures, strangers to our true selves, to one another’ [pp.11-12] (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, 1967). ‘We are dead, but think we are alive. We are asleep, but think we are awake…we are doubly unconscious. We are so ill that we no longer feel ill, as in many terminal illnesses. We are mad, but have no insight [into the fact of our madness]’ (Self and Others, 1961, p.38 of 192). ‘We are so out of touch with this realm [where the issue of the human condition lies] that many people can now argue seriously that it does not exist’ (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, p.105).

My book begins very unusually, which people find distressing, by talking about the process of Resignation. At around 12 to 14 years old adolescents start to think about the human condition, they try to face it down. Let’s imagine we’re looking at Adam Stork 20 generations down the track. By this stage his progeny are now very upset, very angry, egocentric and alienated and they can’t explain why, so they can’t afford to admit it. They have their own children and those children encounter adults that are not admitting that they’re living in a weird, alienated state as R.D. Laing so honestly described it. From the child’s point of view, they’re looking around at the world and it’s crazy! It’s absolutely crazy. As R.D. Laing said ‘Insanity is a perfectly rational adjustment to an insane world’ (Larry Chang, Wisdom for the Soul: Five Millennia of Prescriptions for Spiritual Healing, 2006, p.412), and that’s true, our world is insane—‘there is a veil which is more like fifty feet of solid concrete’ between us and our soul, our true self.

So, the child starts looking around and starts to think, ‘this is really crazy, everyone’s mad, everyone’s insane and no-one’s admitting it’. Everyone is smiling and laughing, buying new pairs of shoes, putting on a brave face but the child can see through that and can see that adult behaviour is false, artificial, escapist, defensive and dishonest. By about 14 years old adolescents start encountering the human condition within themselves—the imperfections, the angers, the insensitivities and lack of concern for others—and it’s when they encounter the human condition within themselves that it all becomes unbearable, so they reach a point where they go into a state of deep, dark depression. What they discover is that they cannot afford to keep looking at the human condition, they have got to block it out, so they resign themselves to blocking out the issue of the human condition from that moment onwards. [See F. Essay 30 on Resignation.]

David Chivers: Can we go back to something you raised at the beginning that just jarred a bit and this might be a good place to finish, because I haven’t felt that you’ve clarified or justified the fact that autism has not got a genetic basis. I think all parents genuinely want to be good parents and make a good effort and there are some who are particularly good, and yet with an autistic child they can make no progress.

Jeremy Griffith: I think that’s a very good question and I will deal now directly with that question.

There is no index at the end of this book because any word or phrase can be easily searched electronically using the ‘Search IS IT TO BE’ facility in the top right-hand corner of the online edition of the book (now the ‘Search FREEDOM’ function available from the ‘Search this site’ button). So if you search ‘Winnicott’ using that facility, you will find that in paragraph 773 (now paragraph 969 of FREEDOM) I quote from the former president of the British Psychological Society, psychiatrist and paediatrician D.W. Winnicott who wrote in his 1996 posthumously published book Thinking About Children that in ‘a proportion of cases where autism is eventually diagnosed, there has been injury or some degenerative process affecting the child’s brain…[however,] in the majority of cases… the illness is a disturbance of emotional development… autism is not a disease. It might be asked, what did I call these cases before the word autism turned up. The answer is…“infant or childhood schizophrenia” [p.200 of 343] [note, ‘schizophrenia’ literally means ‘broken soul’, derived as it is from schiz meaning ‘split’ or ‘broken’, and phrenos meaning ‘soul or heart’]… There are certain difficulties that arise when primitive things are being experienced by the baby that depend not only on inherited personal tendencies but also on what happens to be provided by the mother. Here failure spells disaster of a particular kind for the baby. At the beginning the baby needs the mother’s full attention, and usually gets precisely this; and in this period the basis for mental health is laid down [p.212] …the essential feature [in a baby’s development] is the mother’s capacity to adapt to the infant’s needs through her healthy ability to identify with the baby. With such a capacity she can, for instance, hold her baby, and without it she cannot hold her baby except in a way that disturbs the baby’s personal living process…It seems necessary to add to this the concept of the mother’s unconscious (repressed) hate of the child [p.222] …it is the quality of early care that counts. It is this aspect of the environmental provision that rates highest in a general review of the disorders of the development of the child, of which autism is one [p.212] …Autism is a highly sophisticated defence organization. What we see is invulnerability [p.220] … The child carries round the (lost) memory of unthinkable anxiety, and the illness is a complex mental structure insuring against recurrence of the conditions of the unthinkable anxiety [that results from the mother’s failure to provide her full attention] [p.221]’.

What I’m trying to do is explain that in this story of Adam Stork, after thousands of generations, of course babies are going to come into the world and it’s going to be hugely imperfect. That doesn’t mean at all that mothers aren’t going to try their absolute heart out to be good mothers and as I said, ‘people would rather admit to being an axe murderer than a bad father or mother’. Paragraph 367 of IS IT TO BE (now paragraph 420 of FREEDOM) quotes an article about the failure many mothers feel if they can’t adequately nurture their offspring : ‘For a lot of women the only really important anchor in their lives is motherhood. If they fail in a primary role they feel should come naturally it is devastating for them’ (‘The Deserted Mothers’ Club’, The Weekend Australian Magazine, 30 Nov. 2013).

David Chivers: Yes, totally.

Jeremy Griffith: It’s been an unbearable truth. But now, you see, this is the whole point: we can explain this immensely psychologically upsetting but immensely heroic journey that the human race has been on to find knowledge in the face of unfair criticism, finally we can learn to love ourselves. We can understand that all parents are going to be massively angry, egocentric and alienated sufferers of the human condition and all children coming into the world are going to have to dissociate to some degree to cope and the more extreme the upset they encounter, the more they are going to have to completely dissociate. That is what Winnicott is saying is occurring in autism. But again, that was an unbearable truth. Winnicott and others like him, who dared to say that autism is a result of lack of love, were persecuted and hounded. As Winnicott cautioned, ‘expect resistance to the idea of an aetiology [cause] that points to the innate processes of the emotional development of the individual in the given environment. In other words, there will be those who prefer to find a physical, genetic, biochemical, or endocrine cause, both for autism and for schizophrenia’ (ibid. p.219).

Winnicott warns that people will blame autism and schizophrenia on genes and so forth because it’s an unbearable truth, but now it isn’t an unbearable truth. This is an example of one of the many ‘future shocks’ in this book. And there are so many, it’s just full of heresies. In chapter 1 (now chapter 2 of FREEDOM) the extremely superficial ‘non-answers’ about human behaviour that mechanistic science has been giving us are exposed. In chapter 2 (now chapter 3) the explanation of the human condition exposes the dishonesty of the pseudo-idealistic left-wing and politics is basically brought to an end. In chapter 3 (now chapter 4) God is demystified as Integrative Meaning which makes religion, in a sense, redundant. Chapter 4 (now chapter 5) confronts humans with the historically unbearable truth that nurturing was the prime or main influence in the emergence of our species. We couldn’t admit that nurturing was the prime mover in human development, let alone in our own lives. Chapter 7 (now chapter 8) confronts men and women with the real basis of their relationships—that women aren’t ‘mainframed’ to the battle of the human condition. Chapter 7 also confronts us with the truth of the difference of alienation between races.

Overall, the extreme state of alienation of the whole human race is exposed! Yes, this is truth day, honesty day, exposure day, transparency day, the long-feared, so-called ‘judgment day’! People are going to find it unbearable to face. But I’m trying to say that if we were to sit down with all the parents and all the children on Earth and tell them this wonderful, heroic story about the journey of the human race from ignorance to enlightenment, they will see it’s just the most heroic, wonderful fabulous story and they can all jump around and rejoice and hug each other even though they are all variously upset. We can now understand ourselves! Parents can know that, of course, we are not going to be able to nurture our children adequately under the burden of the human condition. All parents do try their absolute heart out to love their children. It’s not their fault, it’s the history of the human race’s fault! They are part of this heroic journey and inevitably, at the end of a huge, heroic battle all humans are butchered. We are all, as R.D. Laing talked about, massively psychotic and neurotic: ‘We are bemused and crazed creatures, strangers to our true selves, to one another…We are dead, but think we are alive. We are asleep, but think we are awake.’

I agree, David, that parents try their heart out to be loving of their offspring. It’s just that now we can see that we haven’t been able to admit how shocking our upset state is to new generations. That’s why I begin the book by explaining the process of Resignation because that reconnects adults with the truth of just how horrific and afraid we’ve been of the issue of the human condition. With that understanding in tow, we can now go and unpack everything because when you bore down into it, everything is based on these denials, these false accounts of ourselves.

Of course new generations can’t be expected to adequately nurture their children. Children come into the world and they’re not alienated yet, they can see through our disguise—our artificial smiles and all these bright lights. The world is saturated with dishonesty. As Beckett said, ‘we are born astride a grave, the light gleams an instant then it’s night once more’, that’s how brief our soul’s life is before it disintegrates. As Laing says, there’s ‘fifty foot of solid concrete between us and our soul’.

David: Maybe I need to go and reflect on this, it’s been fascinating…

Jeremy: No worries David, thank you very, very much for helping and participating in this discussion. I think it will help a lot of people because a lot of people, well everyone without exception really, will have the same sort of reaction as you’re having and will need the same reassurance and explanation. And they’ll have the same end result where they need to reflect on it, need to think about this. So that will help a lot of people David and I’m very, very grateful and appreciative of your time and your participation.

David: Well, it’s been fascinating, thank you very much.

Jeremy: Thanks, David and I look forward to catching up with you in England very shortly.

David: Yes, goodbye.