Freedom Expanded: Book 1—The Human Condition Explained

Part 3:2 The accountable, true biological explanation of the human condition

Before presenting the fully accountable and thus true biological explanation of the human condition it should again be mentioned that in 2012 the American biologist Edward (E.) O. Wilson published a book titled The Social Conquest of Earth in which he claimed to have explained the human condition. As is fully described later in Part 4:12I, this ‘Theory of Eusociality’ (as E.O. Wilson has termed this so-called explanation of the human condition) doesn’t truthfully explain the human condition at all, rather it attempts to nullify and dismiss it as nothing more than a conflict between supposed selfish and selfless instincts within humans. Unlike the explanation of the human condition that is about to be given, it is not a profound, fully accountable, truthful, real explanation of the psychological dilemma involved in the human condition but a completely false—indeed fake—superficial trivialisation of the subject. As will be documented, all our mythologies, religious teachings, influential thinkers and great writers have recognised, our human condition arises from a consciousness-derived-and-induced psychological insecurity about our fundamental worth and goodness—something this new theory of Eusociality doesn’t even acknowledge, which is, of course, its great appeal; it says, in effect, ‘There is no great underlying insecurity and resulting psychosis and neurosis involved in our so-called human condition, we simply have selfish and selfless instincts that are sometimes at odds.’ With this interpretation, the human condition is rendered benign, virtually inconsequential, which is, of course, immensely relieving, but, nevertheless, an escapist lie. As will be described in Part 4:12, in devising such theories as Social Darwinism, Sociobiology, Evolutionary Psychology, Multilevel Selection and now Eusociality, mechanistic/reductionist science has become masterful at finding new ways to avoid the true, deeply troubled, insecure, fearful, real psychological issue of our human condition. But the reality is the human condition is far from a benign, inconsequential subject for us humans—it has been a profoundly deep, extremely dark and fearful, indeed terrifying, psychological issue, and it is this truthful deep, dark, historically terrifying real human condition that is now going to be properly confronted, explained, reconciled and permanently healed. Real understanding, and, with it, real love, is going to be brought to our human situation. Dishonest, dismissive, escapist denials of the true nature of our species’ unique condition have got the human race nowhere; what we needed was the truth about ourselves—but it had to be the full, compassionate truth, and that is what is about to be presented. The underlying psychosis in human life is finally going to be compassionately fully explained and, by so doing, ameliorated—with the result that human life will be wonderfully TRANSFORMED, as was always the expectation of what would happen when our human condition was finally truthfully and thus properly understood.

I am going to start this fully accountable, truthful, penetrating explanation of our real, psychologically upset human condition with a very simple idea and then keep fleshing it out. What I suggest will happen is that it will gradually become more and more apparent that this explanation really is the unlocking insight into our human behaviour—the key to making sense of this deepest and darkest issue within ourselves of our less-than-ideally-behaved, good-and-evil-afflicted, seemingly highly imperfect, supposedly ‘evil’ human condition; and, following that, that it is the key to understanding all of our human world; and, beyond that, the insight needed to ameliorate or heal our psychologically troubled lives.

Before doing so, however, I should reiterate that the great mystery of our species’ destructive behaviour has seemed to some to be a mystery that could never be explained. For instance, the entry for ‘sin’ in The Bible Reader’s Encyclopedia and Concordance maintains that ‘The problem of the origin and universality of sin…is probably one of those problems which the human mind can never satisfactorily answer.’ But while the real, psychological issue of the human condition has seemed inexplicable and thus unapproachable to many people, it should be remembered that although the question of the origin of the variety of life on Earth was a far less confronting subject to have to look into than the issue of the human condition, it too seemed inexplicable before Charles Darwin explained it; even he described it as having been ‘that mystery of mysteries’ (The Origin of Species, 1859, p.65 of 476). Indeed, prior to finding their explanation, many mysteries can seem overwhelmingly difficult to explain, but certainly none have been as difficult to unlock as the psychological dilemma of our human condition.

Ironically, however, another common trait of mysteries is that often their answer, when finally found, is amazingly simple—despite the difficulties encountered in actually reaching it. In the case of the concept of natural selection it was, in hindsight, such a simple explanation that when the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley first heard it he was prompted to exclaim, ‘How extremely stupid of me not to have thought of that!’ (The Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley, Leonard Huxley, Vol.1, 1900, p.170). Throughout history simplicity has been a hallmark of insightful thought. As the pioneering biologist Allan Savory once observed, ‘whenever there has been a major insoluble problem for mankind, the answer, when finally found, has always been very simple’ (Holistic Resource Management, 1988). The biographer George Seaver also made this point in his biography of the theologian, missionary and physician Albert Schweitzer: ‘Naturalness. That is the keynote of Schweitzer’s thought, life, and personality. The ultimate thought, the thought which holds the clue to the riddle of life’s meaning and mystery, must be the simplest thought conceivable, the most natural, the most elemental, and therefore also the most profound’ (Albert Schweitzer The Man and His Mind, 1947, p.311). So while the crux question facing the human race of the nature of ‘good and evil’ has always seemed inexplicable, it too has an amazingly simple answer. The implications, however, of this explanation could not be more significant, far-reaching or exciting.

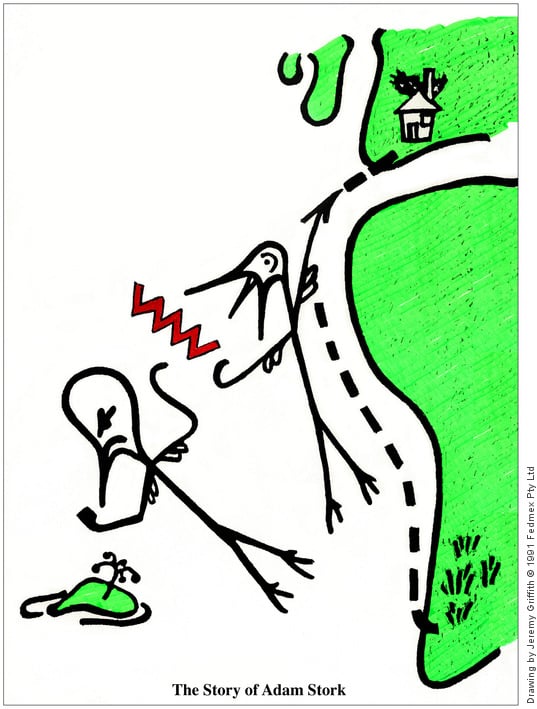

In presenting the explanation, an analogy involving migrating storks is helpful. (The following picture of The Story of Adam Stork depicts this analogy.)

Many bird species are perfectly orientated to instinctive migratory flight paths. Each winter, without ever ‘learning’ where to go and without knowing why, they quit their established breeding grounds and migrate to warmer feeding grounds. They then return each summer and so the cycle continues. Over the course of thousands of generations and migratory movements, only those birds that happened to have a genetic make-up that inclined them to follow the right route survived. Thus, through natural selection, they acquired their instinctive orientation.

Consider a flock of migrating storks returning to their summer breeding roosts on the rooftops of Europe from their winter feeding grounds in southern Africa. Suppose in the instinct-controlled brain of one of them we place a fully conscious mind (I call this stork Adam, because we will soon see that this story parallels the Biblical account in Genesis of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden). So, as Adam Stork flies north he spots an island off to the left with a tree laden with apples. Using his newly acquired conscious mind, Adam thinks, ‘I should fly down and eat some apples.’ It seems a reasonable thought but he can’t know if it is a good decision or not until he acts on it. For Adam’s new thinking mind to make sense of the world he has to learn by trial and error and so he decides to carry out his first grand experiment in self-management by flying down to the island and sampling the apples.

But it’s not that simple. As soon as Adam deviates from his established migratory path, his instinctive self tries to pull him back on course. In effect, it criticises him for veering off course; it condemns his search for understanding. All of a sudden Adam is in a dilemma. If he obeys his instinctive self and flies back on course, he will remain perfectly orientated but he’ll never learn if his deviation was the right decision or not. All the messages he’s receiving from within inform him that obeying his instincts is good, is right, but there’s also a new inclination to disobey, a defiance of instinct. Diverting from his course will result in apples and understanding, yet he already sees that doing so will also make him feel bad.

Uncomfortable with the criticism his newly conscious mind or intellect is receiving from his instinctive self, Adam’s first response is to ignore the temptation the apples present and fly back on course. This makes his instinctive self happy and wins back the approval of his fellow storks, for not having conscious minds they are innocent, unaware or ignorant of the conscious mind’s need to search for knowledge. In the drawing above, we see Adam’s wide-eyed innocent instinctive self (and the other storks), represented by the stork on the right, demanding Adam’s conscious thinking self, depicted on the left, fly back on course. The instinct-obedient stork is following the flight path past the island. Further, since Adam’s instinctive self developed alongside the natural world, it too reminded him of his instinctive orientation, in effect, contributing to the criticism of Adam for his rebellious decision.

Flying on, however, Adam realises he can’t deny his intellect. Sooner or later he must find the courage to master his conscious mind by carrying out experiments in understanding. This time he thinks, ‘Why not fly down to an island and rest?’ Again, not knowing any reason why he shouldn’t, he proceeds with his experiment. And again, his decision is met with the same chorus of criticism—from his instinctive self, the other storks that were ignorant of the need to search for knowledge, and the natural world. But this time Adam defies the criticism and perseveres with his experimentation in self-management. His decision, however, means he must now live with the criticism and immediately he is condemned to a state of upset. A battle has broken out between his instinctive self, which is perfectly orientated to the flight path, and his emerging conscious mind, which needs to understand why that flight path is the correct course to follow. His instinctive self is perfectly orientated, but Adam doesn’t understand that orientation.

In short, when the fully conscious mind emerged it wasn’t enough for it to be orientated by instincts. It had to find understanding to operate effectively and fulfil its great potential to manage life. Tragically, the instinctive self didn’t ‘appreciate’ that need and ‘tried to stop’ the mind’s necessary search for knowledge, as represented by the latter’s experiments in self-management. Hence the ensuing battle between instinct and intellect. To refute the criticism from his instinctive self, Adam needed to understand the difference in the way genes and nerves process information; he needed to be able to explain that the gene-based learning system can, through natural selection, give species orientations to their environment, but that those orientations are not understandings. This means that when the nerve-based learning system gave rise to consciousness and the ability to understand the world, it wasn’t sufficient to be orientated to the world—understanding of the world had to be found. The problem, however, was that Adam had only just taken the first, tentative steps in the search for knowledge, and thus had no ability to explain anything. It was a catch-22 situation for the fledgling thinker, for in order to explain himself he needed the very understanding he was setting out to find. He had to search for understanding, ultimately self-understanding, understanding of why he had to ‘fly off course’, without the ability to first explain why he needed to ‘fly off course’. He couldn’t defend his actions. He had to live with the criticism from his instinctive self and, without that defence, was insecure in its presence.

To resist the tirade of unjust criticism that he was having to endure and mitigate that insecurity, Adam had to do something. But what could he do? If he abandoned the search and flew back on course, sure, he’d gain some momentary relief, but the search would, nevertheless, remain to be undertaken. So all Adam could do was retaliate against the criticism, try to prove it wrong, or simply ignore it—and he did all those things. He became angry towards the criticism. In every way he could he tried to demonstrate his self worth, to prove that he was good and not bad. And he tried to block out the criticism. He became angry, egocentric and alienated or, in a word, upset.

As mentioned, the Concise Oxford Dictionary defines ‘ego’ as ‘the conscious thinking self’ (5th edn, 1964), so ego is another word for the intellect. Thus the word ‘egocentric’ means the intellect became centred or focused on trying to refute the instincts’ criticism; it became focused on trying to prove its worth, prove that it was good and not bad. Adam Stork became preoccupied trying to validate himself, looking for a win, any positive reinforcement that would bring him some sense of worth.

In summary, Adam Stork had no choice other than to resign himself to living a life of anger, egocentricity and alienation as the only three responses available to him to cope with the horror of his situation, his condition. It was an extremely unfair and difficult, and indeed tragic, position for Adam to find himself in, for we can see that while he was good he appeared to be bad and had to endure the horror of his associated psychologically distressed, upset state or condition until he found the defence or reason for his ‘mistakes’. But suffering upset was the price of his heroic search for understanding—it was the tragic yet inevitable outcome in the transition from an instinct-controlled state to an intellect-controlled state. His uncooperative, divisive aggression and his selfish, egocentric efforts to prove his worth and his need to deny and evade criticism became an unavoidable part of his personality. Such was his predicament, and such has been the human condition, for it was within our species that the fully conscious mind emerged.