How to really save the Rhinos

‘We’re not going to win this battle for creation unless we win the battle for greater awareness’

(South African author and eminent conservationist, Sir Laurens van der Post, 1989)

High profile Australian rugby player, David Pocock, recently took time off to join a group of Zimbabwean scouts who protect endangered rhinoceroses from poachers. Posting pictures of himself online with the shirtless group, he wrote: ‘Loved spending some time with the men at the forefront of the effort to protect rhino…Committed, passionate…inspiring to see their commitment in the face of real danger and the challenges of conservation’.

Indeed the plight of the rhinos is one of the major ‘challenges of conservation’, highlighted by the announcement a fortnight ago by the San Diego Zoo of ‘the death of Nola, a critically endangered northern white rhino…[leaving] just 3 northern white rhinos on the planet’, and in November 2011, the declaration by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), that the western black rhinoceros is officially extinct (cnn.com).

Such news is a stark and devastating reminder of the plight of the natural world struggling under the weight of indifference of seven billion humans. In unscrambling this mess of how we have driven these magnificent creatures to extinction, we can clearly see several key factors leading to this dire situation. The spread of industrial agriculture throughout Africa in the 20th century resulted from the ‘scramble for Africa’ by established imperial empires and called for the removal of wild game, which inherently led to an increase in game hunting for sport. Journal entries of this period from white hunters such as the famous J.A. Hunter, document how extensive the killing was. Hunter records having dispatched ‘996 Rhinos’ from ‘August 29th 1944 to October 31st 1946’. This depletion has been back-ended by a demand for bushmeat from a burgeoning population and the black market trade in rhino horns for ornamentation and traditional Chinese medicinal purposes, which saw, ‘in East Africa…in the 1970s, the numbers [of rhinos poached for their horns] skyrocket…to 3,400 kilograms (7,480 pounds), and every year in that decade, 1,180 rhinos died.’ (Tiger Bone & Rhino Horn: The Destruction of Wildlife for Traditional Chinese Medicine, Richard Ellis, 2013, p.132 of 312).

The shocking fact is that the rhino is but one of many species of animal on the brink of extinction. According to the IUCN, as of 2014, there were 2464 critically endangered animals in the world (animals categorized as facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild) (wikipedia.org).

And whilst we flippantly ‘like’ pictures of Pocock lifting weights with the Malilangwe Scouts in a show of support as we scroll through our social media accounts, or as Scientific American journalist John Platt noted (following the announcement of the extinction of the western black rhino), ‘unleash a veritable tsunami of sadness…on social media’ (blogs.scientificamerican.com), surely at some point we must stop and ask the hard questions. If we are to genuinely turn the tide on species depletion and environmental destruction, we have to look within and address our species collective psychosis—the human condition—to understand why such destruction of our natural world occurs and why indifference and apathy prevail (despite the backslapping of Pocock and the ‘tsunami of sadness’ on social media).

Back in 1989 during a filmed interview, the prophetic South African author, explorer and eminent conservationist, Sir Laurens van der Post, reflected on man’s relationship and impact on the natural world. He began by reflecting on the plight of the Rhinos, recalling how when he was six, he was ‘horrified to hear that there were only nine white rhinos alive in the world…What I felt then…has grown into a certainty that unless we succeed in arresting the assault and violation of the natural world, we ourselves will not survive’ (Quadrant: The Journal of Contemporary Jungian Thought. Vol 23, No. 2, viewed 07/12/15 at https://msuweb.montclair.edu/~sotillos/ourmotherlvdp.html). He went on to recognise that ‘[the] battle started, or the threat started, long, long, before the rhino was threatened, perhaps long before the rhino existed, long before I was born...’. And significantly, ‘It seems to me that the most important thing we have to grasp is how old this battle is…[the] devastation, this spoliation of nature has gone on for centuries, and unless we realize how old, how stubborn, how devastating is this thing in us that exploits nature this way, we will not tackle the problem properly…where does this strange urge to destroy come from?’.

Van der Post points to the emergence of consciousness as the most significant aspect in our species, citing ‘the greatest of all classical myths’, the ancient Greek myth of Prometheus. He states the myth ‘…says to us very clearly where it began. It began with the Promethean gift of fire. When Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to human beings, the trouble began…this fire, of course, was consciousness…The gods suddenly allowed a particular animal species on earth to become conscious. And in the history of life on earth...consciousness is a young phenomenon. It’s young, it’s new, and it’s vulnerable...’, with the result being ‘…this great power of consciousness has gradually corrupted us…we’re not going to win this battle for creation unless we win the battle for greater awareness…time is going to come when the earth itself will turn bitter, when nature will turn bitter…when everything on earth will turn against us and we’ll vanish.’

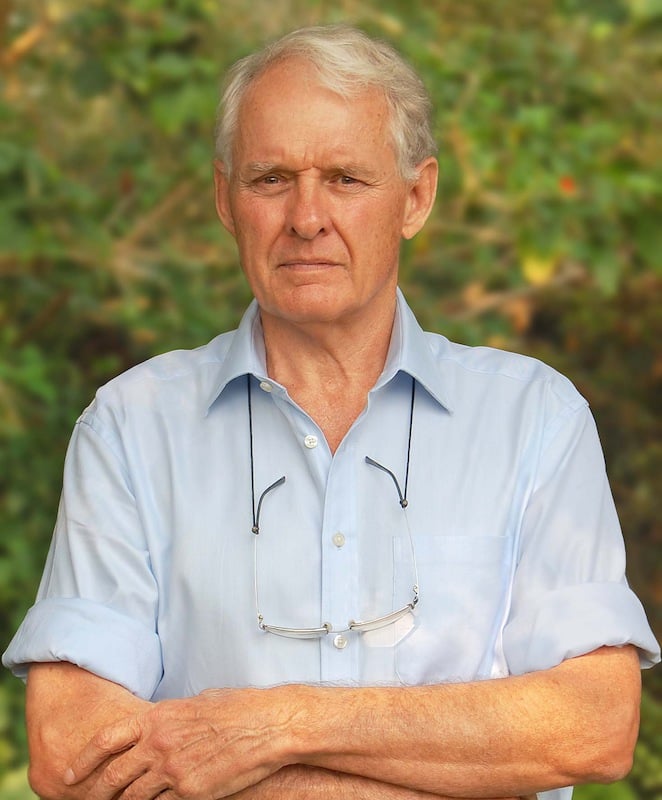

This ‘battle for greater awareness’ to prevent ‘the assault and violation of the natural world, [where] we ourselves will not survive’ has been the undertaking of one of the most remarkable thinkers of all time, Australian biologist Jeremy Griffith.

(In fact, Griffith turned his attention to the urgent plight of the human race following his extensive six year campaign to save the Thylacine (Tasmanian Tiger) from extinction in the late 1960’s, during which, sadly, despite his extraordinary efforts, he came to the conclusion that the tiger was indeed extinct. He has been thinking and writing about the human condition ever since).

Griffith has plumbed the depths of humanity to find the redeeming understanding of our troubled selves, winning this ‘battle for greater awareness’ no less. And, as van der Post also identified, the key to winning this battle, and the path towards ending the destruction of the planet and our species, is in understanding our unique, fully conscious mind.

In his upcoming book ‘FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition’, Griffith explains that we were once a species governed by our instincts, as all other animals are, but with the emergence of consciousness in our species development some two million years ago, a battle effectively broke out between our already established gene-based operating system and our newly acquired nerve-based system with its incredible capacity to understand the world. Basically, when our conscious mind emerged it was not enough for it to be orientated by instincts, it had to diverge from them and find understanding if it was to fulfill its potential to manage life from a conscious basis.

The problem was that when the conscious mind began to try to manage things, an unavoidable conflict emerged between it and our pre-established instinctive orientations.

The instincts in effect ‘criticised’ and ‘tried to stop’ our search for knowledge. And we weren’t in a position to explain why we were deviating from our instincts, so we couldn’t refute this criticism. But we had to defend ourselves in some way, which we did in three ways: we attacked the instincts’ unjust criticism; we tried to block-out the instincts’ unjust criticism from our mind; and we tried to prove the instincts’ unjust criticism wrong. Humans’ upset, angry, alienated and egocentric state appeared.

It is important to note that the significance of the explanation put forward by Griffith lies in the fact that not only is the source of our psychologically upset state addressed (in outlining the battle between our instincts and the newly emerged intellect), but the ‘burden of guilt’ is lifted from our species—which has not been possible until we have had the complete and dignifying explanation of what occurred when our species developed consciousness—outlined in Chapter 1:3 of FREEDOM: ‘we can see how absolutely wonderfully exonerating and psychologically transforming this psychosis-addressing-and-solving explanation of the human condition is, because after 2 million years of uncertainty it allows all humans to finally understand that there has been a very good reason for our angry, alienated and egocentric lives. Indeed, this fact of the utter magnificence of the human race—that we are, in truth, the heroes of the story of life on Earth—brings such intense relief to our angst-ridden cells, limbs and torsos that it will seem as though we have thrown off a shroud of heavy weights. The great, heavy burden of guilt has finally been lifted from the shoulders of humans…

Importantly, it is this “ability now to explain and understand that we are actually all good and not bad [that] enables all the upset that resulted from being unable to explain the source of our divisive condition to subside and disappear. Finding understanding of the human condition is what rehabilitates and transforms the human race from its psychologically upset angry, egocentric and alienated condition.’

The importance of Griffith’s explanation of the human condition and it’s implications cannot be overstated. Van der Post could clearly see the dire situation facing humanity: ‘we’re not going to win this battle for creation unless we win the battle for greater awareness’; what Griffith presents allows this victory to be achieved. It is THE most significant contribution to understanding ourselves to have ever been articulated.

The efforts of the Malilangwe Scouts and fly-in crusader David Pocock are admirable, but for all of us backslapping him and contributing to the ‘tsunami of sadness’ on social media, the time has come for a profound approach. The real fight is bringing about the ‘greater awareness’ so desperately needed for our species, to end all the ‘devastation [and] spoliation of nature [that] has gone on for centuries’. This book achieves the unimaginable and it couldn’t come at a more critical time. </p >

Above: Jeremy Griffith (left) and fellow patron of the World Transformation Movement, Tim Macartney-Snape, with the late Sir Laurens van der Post, London 1993.

Please wait while the comments load...

Comments