1. ABOUT THE HUMAN CONDITION

AND ITS RESOLUTION

WTM FAQ 1.47 How does Jeremy Griffith’s explanation of the human condition differ from the theories of Freud or Jung? / What was Sir Laurens van der Post’s contribution to Jeremy Griffith’s explanation of the human condition?

Jeremy Griffith’s response (from his book The Therapy for the Human Condition):

The Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud is regarded as the father of modern psychoanalysis. He began this terrifying journey into the issue of our seemingly indefensible, angry, egocentric and alienated, soul-corrupted, we-must-be-‘evil’-‘worthless’-monsters human condition, when, after great personal difficulty, he was sufficiently able to penetrate the terrifying depths where the issue of the human condition resides to discover the truth that everyone has a ‘personal unconscious’, a personal repressed psychologically distressed condition or psychosis. As the British psychiatrist D.W. Winnicott wrote, ‘The word “unconscious”…has been used for a very long time to describe unawareness…there are depths to our natures which we cannot easily plumb…a special variety of unconscious, which he [Freud] named the repressed unconscious…what is unconscious cannot be remembered because of its being associated with painful feeling or some other intolerable emotion’ (Thinking About Children, 1996 posthumous publication of his writings, p.9 of 343). The Scottish psychiatrist R.D. Laing described how difficult the journey into this ‘repressed unconscious’ world was for Freud when he wrote that: ‘The greatest psychopathologist has been Freud. Freud was a hero. He descended to the “Underworld” and met there stark terrors…We who follow Freud have the benefit of the knowledge he brought back with him’ (The Divided Self, 1960, p.25 of 218).

Having heroically dug up the truth of a personal repressed unconscious, Freud then however veered off that path of truthful thinking and reverted to the escape-from-the-human-condition ‘savage instincts’ excuse. Freud believed that the ‘ID’, our unconscious, instinctive mind, contained primitive selfish ‘savage’ urges that the conscious mind or ‘ego’ has to control, writing, for example, that ‘men are not gentle, friendly creatures wishing for love, who simply defend themselves if they are attacked, but that a powerful measure of desire for aggression has to be reckoned as part of their instinctual endowment (Civilization and its Discontents, 1930, tr. Joan Riviere, ch. V, p.85 of 144), and ‘Culture has to call up every possible reinforcement in order to erect barriers against the aggressive instincts of men’ (ibid. p.86). The truth is that our instinctive self is completely cooperative, selfless and loving and comes from a time when our ape ancestors lived in that state; and further, our aggressive and selfish behaviour is psychological in origin, the result of a clash between our instincts and intellect. Freud also falsely maintained that our morals are learnt and held by the ‘superego’ as a way of restraining our ‘instinctual’ ‘aggression’, when the truth is our morals are the expression of our loving, cooperative instincts or soul. Freud even directly denied that our species once lived in a ‘golden age’ of cooperative and loving innocence by claiming that this idea of a ‘golden age’ in our species’ past was nothing more than nostalgia for the protected bliss of infancy. As the author Richard Heinberg noted, this ‘Paradise myth as an unconscious projection of memories of infancy…is what Freud proposed in his theory of the development of the personality—that infancy is a Paradise lost’ (Memories & Visions of Paradise, 1990, pp.193-194).

Freud’s protégé, the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung, was an honest, actually partially honest, thinker who took the next step towards achieving real therapy for humans by trying to recognise and bring understanding to our psychotic and neurotic human condition. Jung added to Freud’s acknowledgement that we have a personal unconscious the recognition that we also have a ‘collective unconscious’, a collective, shared-by-all part of ourselves that we have also repressed. In his 2000 book, Life of Jung, Ronald Hayman gave this summary of Jung’s ‘heroic’ journey into the ‘unconscious counterposition’ in us humans, and how the confronting truths that exist there nearly destroyed Jung, but also how facing those truths allowed him to think truthfully and thus effectively enough to come up with the important insights about human existence he found. Hayman wrote: ‘He [Jung] claimed to have acquired the knack of catching unconscious material “in flagrante”, and his [1962] book Memories, Dreams, Reflections suggests his behaviour was heroic—that he was making a dangerous expedition into the unconscious for the sake of scientific discovery…In December 1913, he says, he decided to drop downwards. “I let myself fall, it was as if the floor literally gave way underneath me and I plummeted into dark depths”…It took about three years to recover from the [resulting psychological] breakdown…It was during Jung’s breakdown that he arrived at some of his most important concepts’ (‘An edited extract from Life of Jung’, Good Weekend mag. Sydney Morning Herald, 5 Feb. 2000; see www.wtmsources.com/265).

For a description of the most important of the ‘important concepts’ Jung found on his heroic journey into the unconscious, Jung’s friend, Sir Laurens van der Post, reported that firstly, Jung was heroically motivated by concern that ‘Man everywhere is dangerously unaware of himself. We really know nothing about the nature of man, and unless we hurry to get to know ourselves we are in dangerous trouble’ (Jung and the Story of Our Time, 1976, p.239 of 275)—in fact, Jung is renowned for emphasising the truth that ‘wholeness for humans depends on the ability to own our own shadow’. Van der Post then went on to describe how Jung achieved a ‘breakthrough into this great new world within. It was as momentous as the breakthrough into the nature of the atom’ (Jung and the Story of Our Time, p.61), ‘he was the very first great explorer in the twentieth-century’ (p.63), the result of which was that ‘Jung went deeper [than Freud’s ‘personal unconscious’], to uncover below what one might call a racial or historical unconscious, leading finally to the greatest area of all which he called the “collective unconscious”’ (p.145).

However, while Jung managed to recognise that we have a ‘collective unconscious’, he was not able to go beyond that with his courageous-but-ultimately-afraid thinking and admit that our instinctive, shared-by-all, ‘collective unconscious’ is our species’ instinctive memory of once living in a cooperative and loving state. In fact, like Freud, Jung veered off from his brave truthful thinking and reverted to the escape-from-the-human-condition, hide-in-Plato’s-dark-cave, ‘savage instincts’ excuse for our divisive behaviour. For example, Jung wrote that ‘The shadow is that hidden, repressed, for the most part inferior and guilt-laden personality whose ultimate ramifications reach back into the realm of our animal ancestors’ (Aion, p.266), and that ‘Man has developed consciousness slowly and laboriously, in a process that took untold ages to reach the civilized state. And this evolution is far from complete, for large areas of the human mind are still shrouded in darkness’ (Man and His Symbols, 1964, Part 1, p.6 of 415). Indeed, like Freud, Jung directly denied the truth of our species’ cooperative and loving instinctive past by dismissing the idea of a ‘golden age’ in our species’ collective memory as nothing more than, as Richard Heinberg noted, ‘an analogy for the mother-infant relationship…Carl Jung went on to incorporate the Paradise-as-infancy concept into his theory of the archetypes. For Jung, Paradise is the positive aspect of the archetypal mother, the infant’s source of security and nourishment…[subscribing to the view] that the Garden of Eden was not a geographical place, but a metaphor for the womb’ (Memories & Visions of Paradise, pp.193-194).

So, while Freud and Jung bravely revealed that we humans are living in denial of a great deal of truth—that, as they described it, we suffer from a ‘personal’ and ‘collective’ psychosis—neither attempted to confront what it was that we were particularly repressing or living in unconscious denial of, which is our species’ cooperative and loving past. They talked a lot about our psychosis and how it wrecks our lives and how we need to do something about that if we are to become ‘whole’ or sane, but they weren’t able to confront what our psychosis actually is, which is denial or repression of our cooperative and loving instinctive self or soul. Freud had people lying on his iconic couch opening up about their insecurities and psychological pain, which was a big step in honesty from the resigned strategy of every moment determinedly denying that there was anything particularly wrong in our lives and that everything was basically fine; and Jung spoke of archetypes and encouraged people to analyse the expressions of their subconscious in their dreams, and emphasised the need to ‘individuate’ or unify our split selves. But the ‘elephant in the living room’ of human life of how we had almost completely corrupted our species’ original instinctive self or soul was being avoided. Basically, Freud and Jung didn’t take people outside of Plato’s metaphorical dark cave where they were living in fearful denial of the issue of the human condition. And what is significant about them not taking people outside Plato’s cave of denial where they would have to actually confront the human condition, the truth of our species’ 2-million-years corrupted state, is that everyone could relatively easily relate to Freud and Jung, which is why they became such famous therapists. As the human race has become increasingly upset, people have found the superficial honesty of talking about psychosis and neurosis, of discussing how much they are suffering psychologically, of admitting to being ‘damaged’, and of referring to the ‘hurt child within’, to be quite cathartic. Indeed, such superficial honesty where you pretend to be talking about the human condition when you actually aren’t could be very relieving—which is why dishonest, non-human-condition-confronting, superficial ‘pop psychology’ and pseudo therapy is now immensely popular; however, because it is only superficial it is ultimately ineffective, and as a result the human race has continued to plunge to terminal levels of psychosis!

Sir Laurens van der Post’s contribution to my explanation of the human condition

The next step in the all-important, if the human race is to be saved from extinction, journey of honest thinking about our species’ psychologically upset condition was by someone who was not psychologically insecure like Freud and Jung were, and virtually every human is. Rather, the next step was taken by someone who must have largely escaped encountering the horrors of the human condition during his upbringing and as a result was exceptionally uncorrupted in soul and thus exceptionally sound and secure in himself, because he was able to think sufficiently truthfully about the human condition to admit that our much denied and repressed shared-by-all ‘collective unconscious’ is our species’ instinctive memory of having once lived cooperatively, selflessly and lovingly. That person was the just mentioned friend of Jung, the very great South African philosopher Sir Laurens van der Post, because it was he, in his many books, especially in his books about the relatively innocent Bushman or San people of southern Africa, who acknowledged the truth of our species’ original state of innocence. For instance, Sir Laurens wrote about the Bushman that ‘mere contact with twentieth-century life seemed lethal to the Bushman. He was essentially so innocent and natural a person that he had only to come near us for a sort of radioactive fall-out from our unnatural world to produce a fatal leukaemia in his spirit’ (The Heart of the Hunter, 1961, p.111 of 233). Even more explicitly, he wrote that ‘This shrill, brittle, self-important life of today is by comparison a graveyard where the living are dead and the dead are alive and talking [through our soul] in the still, small, clear voice of a love and trust in life that we have for the moment lost…[There was a time when] All on earth and in the universe were still members and family of the early race seeking comfort and warmth through the long, cold night before the dawning of individual consciousness in a togetherness which still gnaws like an unappeasable homesickness at the base of the human heart’ (Testament to the Bushmen, 1984, pp.127-128 of 176).

However, while Sir Laurens was able to resurrect the truth of our species’ original state of innocence, there still remained the task of finding the testable, verifiable, understandable, science-based, reconciling explanation for why we corrupted such a wonderful, cooperative and loving existence. As Sir Laurens wrote: ‘I had a private hope of the utmost importance to me. The Bushman’s physical shape combined those of a child and a man: I surmised that examination of his inner life might reveal a pattern which reconciled the spiritual opposites in the human being and made him whole…it might start the first movement towards a reconciliation’ (The Heart of the Hunter, p.135).

It was this final step in the honest journey of addressing-not-avoiding the human condition that I was able to contribute, presenting the fully accountable, instinct vs intellect biology ‘which reconciled the spiritual opposites’ of our lost state of innocence with our present corrupted, seemingly evil human condition and makes us ‘whole’. Greatly assisted by the honesty of Sir Laurens’s writings about the relatively innocent Bushman, I was able to hold onto all the truthful thoughts I had as a young man, especially about the original innocence of the human race, and from there go on to find the biological defence for our corrupted condition that makes the effective therapy of our corrupted condition possible. As Professor Harry Prosen, a former President of the Canadian Psychiatric Association, said, ‘I have no doubt this biological explanation of the human condition is the holy grail of insight we have sought for the psychological rehabilitation of the human race.’

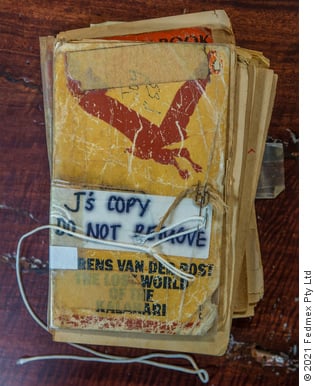

Showing how precious Sir Laurens’s writings have been to me, this is my present set

—my original set being so tattered I could no longer use them—of Sir Laurens’s two main

books about the Bushman, The Lost World of the Kalahari and The Heart of the Hunter.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

For the actual explanation of the human condition see THE Interview or read chapter 1:3 of FREEDOM. See FAQ 5.2 for the explanation of how we humans acquired our all-loving, unconditionally selfless moral conscience.