5. THE GREAT SCIENTIFIC QUESTIONS

WTM FAQ 5.2 How did we humans acquire our all-loving, unconditionally selfless moral conscience?/ What do the nurtured and cooperative bonobos tell us about our own evolutionary heritage? / How do you account for reports that bonobos hunt and kill, and even that male bonobos are more aggressive than chimpanzee males?

How did we humans acquire our all-loving, unconditionally selfless moral conscience?

When Charles Darwin wrote that ‘The moral sense perhaps affords the best and highest distinction between man and the lower animals’ (The Descent of Man, 1871, ch.4) he was recognising that humans have cooperative and loving moral instincts, the ‘voice’ or expression of which is our conscience. And in order to have an instinctive altruistic moral nature, it follows that our distant ape ancestors must have been cooperative and loving, not competitive and aggressive like other animals. But, since altruistic, unconditionally selfless genetic traits are self-eliminating, and therefore seemingly cannot develop in animals, that leaves the question of how could we humans have developed them?

The answer was through nurturing.

While a mother’s maternal instinct to care for her offspring is selfish (which, as mentioned, genetic traits have to be for them to reproduce and carry on into the next generation), from the infant’s perspective the maternalism has the appearance of being selfless. From the infant’s perspective, it is being treated unconditionally selflessly—the mother is giving her offspring food, warmth, shelter, support and protection for apparently nothing in return. So it follows that if the infant can remain in infancy for an extended period and be treated with a lot of seemingly altruistic love, it will be indoctrinated with that selfless love and grow up to behave accordingly—and over many generations that behaviour will become instinctive because genetic selection will inevitably follow and reinforce any development process occurring in a species; the difficulty was in getting the development of unconditional selflessness to occur in the first place, for once it was regularly occurring it would naturally become instinctive over time. And being semi-upright from living in trees, and thus having their arms free to hold a dependent infant, it was the primates who have been especially facilitated to support a prolonged and deeply connected mother infant relationship and so develop this nurtured, loving, cooperative nature. So it was through this ‘love-indoctrination’ process that our primate ancestors developed our moral conscience.

While this nurturing explanation for our species’ moral nature is reasonably straight forward, and even obvious, there has been a huge problem admitting it. While our distant ape ancestors did live a nurtured, cooperative and loving life (which there’s ample evidence for), when our ancestors became conscious some 2 million years ago this situation completely changed. As explained in THE Interview, and fully in chapter 3 of biologist Jeremy Griffith’s definitive book on the explanation of the human condition, FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition, the emergence of consciousness led to a psychologically upsetting battle with our already established cooperative and loving instincts, a battle that unavoidably made us angry, egocentric and alienated. And once we became victims of that upsetting angry, egocentric and alienating battle, obviously no child was able to be given the amount of nurturing all infants were able to receive prior to the emergence of that distressing battle. But until we could explain this reason for our so-called ‘corrupted’ or ‘fallen’ human condition, and thus understand why we unavoidably lost the ability to adequately nurture our infants, the whole idea of a cooperative and loving past that was developed through nurturing was an unbearable truth that we had no option but to deny. It is only now that that we can explain the human condition that it becomes safe to finally admit that nurturing is what made us human—that it was nurturing that gave us our moral soul and created humanity.

The nurturing explanation of humans’ moral instincts is presented in Freedom Essay 21, and in full in chapter 5 of FREEDOM.

What do the nurtured and cooperative bonobos tell us about our own evolutionary heritage?

(This part of the FAQ is an adapted excerpt from Jeremy Griffith’s Freedom Essay 21.)

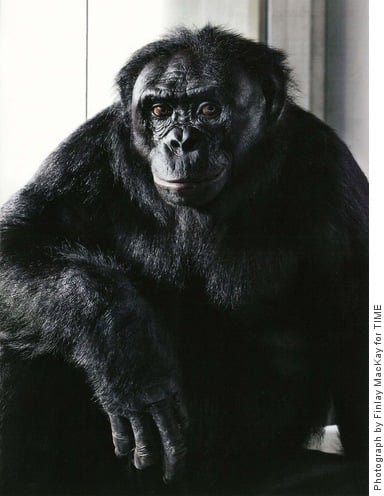

Bonobos, the ape species who live south of the Congo River in Africa, are the most cooperative, selfless and loving of all non-human primates; they are also extraordinarily matriarchal, or female role focused, and extraordinarily focused on nurturing their infants, as this quote evidences: ‘Bonobo life is centered around the offspring. Unlike what happens among chimpanzees, all members of the bonobo social group help with infant care and share food with infants. If you are a bonobo infant, you can do no wrong…Bonobo females and their infants form the core of the group’ (Sue Savage-Rumbaugh & Roger Lewin, Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind, 1994, p.108 of 299).

As to how cooperative, selfless and loving bonobos are, the following quotes (which are all referred to in chapter 5 of FREEDOM, and partly referred to in Part 3 of THE Interview) provide powerful evidence. Firstly, from filmmakers who were producing a documentary about them: ‘they’re surely the most fascinating animals on the planet. They’re the closest animals to man [in that they share 99 percent of our genetic make-up]. They’re the only animals capable of creating the same “gaze” as a human. When you look at a bonobo you’re taken aback because you can see behind the eyes it’s not just curiosity, it’s understanding. We see human beings in the eyes of the bonobo…Once I got hit on the head with a branch that had a bonobo on it. I sat down and the bonobo noticed I was in a difficult situation and came and took me by the hand and moved my hair back, like they do. So they live on compassion, and that’s really interesting to experience’ (accompanying film discussing the production of the French documentary Bonobos, 2011).

Yes, as bonobo zoo keeper Barbara Bell said, ‘Adult bonobos demonstrate tremendous compassion for each other…For example, Kitty, the eldest female, is completely blind and hard of hearing. Sometimes she gets lost and confused. They’ll just pick her up and take her to where she needs to go’ (Chicago Tribune, 11 Jun. 1998). Bonobos’ unlimited capacity for love is also apparent in this wonderful first-hand account from bonobo researcher Vanessa Woods: ‘Bonobo love is like a laser beam. They stop. They stare at you as though they have been waiting their whole lives for you to walk into their jungle. And then they love you with such helpless abandon that you love them back. You have to love them back’ (The Guardian, 1 Oct. 2015).

The consequences of this nurturing of unconditional love in bonobos is apparent in this report from researchers: ‘bonobos historically have existed in a stable environment rich in sources of food…and unlike chimpanzees have developed a more cohesive social structure’ (Takayoshi Kano & Mbangi Mulavwa, ‘Feeding ecology of the pygmy chimpanzees (Pan paniscus)’; The Pygmy Chimpanzee, ed. Randall Susman, 1984, p.271 of 435). For example: ‘up to 100 bonobos at a time from several groups spend their night together. That would not be possible with chimpanzees because there would be brutal fighting between rival groups’ (Paul Raffaele, ‘Bonobos: The apes who make love, not war’, Last Tribes on Earth.com, 2003; see www.wtmsources.com/143). (Chapter 5 of FREEDOM includes many images of bonobos that evidence just how nurturing, gentle and cooperative they are.)

It might be mentioned that another consequence of our ape ancestors having been nurtured with unconditional selflessness or love is that that orientation to love liberated the development of a fully conscious mind, which this further quote from Barbara Bell evidences is emerging in bonobos: ‘They’re extremely intelligent…They understand a couple of hundred words…It’s like being with 9 two and a half year olds all day’ and ‘They also love to tease me a lot…Like during training, if I were to ask for their left foot, they’ll give me their right, and laugh and laugh and laugh.’ (See some extraordinary footage of the bonobo ‘Kanzi’, revealing just how conscious bonobos are, in Freedom Essay 21; and read about the emergence of consciousness in F. Essay 24 and chapter 7 of FREEDOM.)

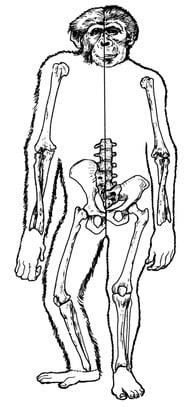

Unlike our primate ancestors, it is clear that bonobos haven’t completed the nurturing based love-indoctrination process, because there are remnants of sexual opportunism and aggression in their behaviour, however, all the descriptions just included (and you can read many more in chapter 5 of FREEDOM) provide powerful insights into how extraordinarily cooperative, selfless and loving they, our closest living relative, are. In fact, the following picture shows just how similar our species are, comparing as it does the skeleton of our early australopithecine ancestor (who lived between 3.9 and 3 million years ago) with the skeleton of a bonobo. The truth is that our ancestors are far more similar to bonobos with regard to their size, their bipedality, environment, lack of large canines, and lack of size differentiation between males and females, than any other existing primate—which indicates that our ancestors followed a similar path of development to the bonobos. So the evidence is that it was through the nurturing, love-indoctrination process that we acquired our altruistic moral nature.

Left side: Bonobo skeleton. Right side: Early australopithecine.

(Drawing by Adrienne L. Zihlman from New Scientist, 1984)

Indeed, the recent astonishing fossil discoveries, particularly those of the 4.5 million year old Ardipithecus that revealed these similarities between our ancestors and bonobos, have led the leading anthropologist C. Owen Lovejoy to acknowledge that ‘our species-defining cooperative mutualism can now be seen to extend well beyond the deepest Pliocene [well beyond 5.3 million years ago]’ (‘Reexamining Human Origins in Light of Ardipithecus ramidus’, Science, 2009, Vol.326, No.5949). (Much more can be read in Freedom Essay 22 about the insights being gleaned from the fossil record.)

What about reports that bonobos hunt and kill, and even that male bonobos are more violent than chimpanzee males?

As explained in the first part of this FAQ, until we could explain the reason for our so-called ‘corrupted’ or ‘fallen’ human condition, and thus understand why we humans unavoidably lost the ability to adequately nurture our infants, the whole idea of a cooperative and loving heritage that was developed through nurturing was an unbearable truth that we had no option but to deny (read more about this denial in chapter 5:7 of FREEDOM).

It follows that the nurturing-focused, peaceful and gentle bonobos have been extremely confronting of our present non-peaceful and non-gentle condition; and so ever since bonobos were recognised as a species in 1929, people have been looking for ways to negate the condemning evidence they provide of humans having a nurtured, cooperative, loving past. The primatologist Frans de Waal explained the main ways that human-condition-avoiding mechanistic science has attempted to do this: ‘Two strategies have emerged to keep bonobos at a distance so as to preserve chimpanzee-based scenarios of human evolution, which traditionally emphasize warfare, hunting, tool use, and male dominance. The first strategy is to describe the bonobo as an interesting but specialized anomaly that can be safely ignored as a possible model of the last common ancestor…The second strategy, adopted by [Craig] Stanford, is to minimize the differences between the two Pan species: if bonobos behave, by and large, like chimpanzees, there is no reason to question the latter species’ prominence as a model’ (‘The Social Behavior of Chimpanzees and Bonobos: Empirical Evidence and Shifting Assumptions’, Current Anthropology, 1998, Vol.39, No.4). (Chapter 6:6 of FREEDOM provides a full exposé of mechanistic science’s attempts to negate the nurtured, loving example provided by bonobos; we also recommend chapter 8:12, which explains how mechanistic science similarly tried to negate the confronting evidence of our species’ cooperative and loving past provided by the gentle and cooperative San Bushmen of southern Africa.)

The first strategy of simply ignoring the anomaly that bonobos represented was so successful that the first in-depth study of bonobos, which only occurred in 1954, was ‘ignored and forgotten by the scientific community’ (Frans de Waal & Frans Lanting, Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape, 1997, p.11 of 210) because it dared to describe them as ‘an extraordinarily sensitive, gentle creature, far removed from the demoniacal primitive force of the adult chimpanzee’ (E. Tratz & H. Heck, ‘Der africkanische Anthropoide “Bonobo”: Eine neue Menschenaffengattung’, Säugetierkundliche Mitteilungen, Vol.2, 1954).

The second strategy took various forms. One was to ‘accuse’ bonobos of systematically hunting and killing other animals like chimpanzees do. However, as is explained in chapter 2:11 of FREEDOM, while bonobos have been known to opportunistically capture and eat small game, including small monkeys, and even larger colobus monkeys (see, for example, National Geographic’s Bonobos Hunt Down Colobus Monkeys extract; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FiHrUpnkfZk&list=WL&index=40), to supplement their diet with protein, they are not known to routinely hunt down and eat large animals like chimpanzees do, with ‘hunting behavior [by bonobos] very rare’ (Tetsuya Sakamaki quoted by David Quammen, ‘The Left Bank Ape’, National Geographic, Mar. 2013). It is even recorded that ‘at the Lilungu site, bonobos catch guenons [monkeys] and colobus monkeys but do not eat them [unlike what occurred in the video above of bonobos hunting and actually eating colobus monkeys], and at Wamba, bonobos and red colobus monkeys have been seen to engage in mutual grooming’ (M. Surbeck & G. Hohmann, Current Biology, 2008, Vol.18, No.19) which is behaviour that would be unthinkable in a chimpanzee.

Similarly, mechanistic science has tried to portray bonobos, particularly male bonobos, as being as aggressive as chimpanzees. A 2024 study, led by Boston University’s Dr Maud Mouginot, purported to count instances of ‘aggression’ between bonobo males, and found that male bonobos apparently engage in aggressive acts three times as often as chimpanzees, and that ‘more aggressive [bonobo] males obtained higher mating success [than less aggressive males]’ (Mouginot et al, ‘Differences in expression of male aggression between wild bonobos and chimpanzees’, Current Biology, 2024, Vol.34, No.8). However, the types of aggression counted were often mild, including instances of ‘pulling and kicking’, and the report also noted the following very significant difference between bonobos and chimpanzees: ‘male chimpanzees sexually coerce females and sometimes kill conspecifics [other chimpanzees], whereas male bonobos exhibit less sexual coercion and no reported killing [of other bonobos]’ (ibid). Clearly there is a world of difference between bonobo and chimpanzee ‘aggression’: male chimpanzees use violence to coerce females into sex, regularly kill competing males, practice infanticide and form troops that raid and kill members of neighbouring chimpanzee groups; whereas in bonobo society, females rule and choose their mates, males bicker but have never killed another bonobo, and whole groups mingle peacefully with neighbouring groups. This important clarification about the Mouginot report was made in a published letter in New Scientist magazine by the Director of The Bonobo Conservation Initiative Australia, Angus Gemmell (‘Bonobo aggression minor compared with chimps’, 24 Apr. 2024), and also by Gisela Kaplan, Emeritus Professor in Animal Behaviour at the University of New England in Australia, when she said that ‘she found the paper extremely frustrating and that the word “aggression” is being misused. Chimpanzee groups are ruled by one dominant male, whereas bonobos are ruled by females. Competitions for dominance and mating rights in bonobos shouldn’t be confused with aggression’ (James Woodford, ‘“Peaceful” male bonobos may actually be more aggressive than chimps’, New Scientist, 12 Apr. 2024).

Despite this important clarification, consider the headlines that publicised the 2024 report: ‘No “Hippie Ape”: Bonobos Are Often Aggressive, Study Finds’ and ‘Male Bonobos, Close Human Relatives Long Thought to Be Peaceful, Are Actually Quite Aggressive’ and ‘“Peaceful” male bonobos may actually be more aggressive than chimps’. This shameless misrepresentation evidences how confronting bonobos are, and how desperate for relief from their condemning example we humans have been. Yes, the need for relief in these headlines is palpable!

Again, unlike our ancestors, the bonobos haven’t completed the nurturing based love-indoctrination process, and so there are remnants of sexual opportunism and aggression in their behaviour, however, the inescapable, glaring, overall truth, as evidenced in the second part of this FAQ—and in fact by any honest and sensitive observation of bonobo behaviour—is that bonobos are extraordinarily nurturing, loving, cooperative and gentle.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Again, the nurturing explanation of humans’ moral instincts, including extraordinary evidence from bonobos and the fossil record, is presented in Freedom Essay 21, Freedom Essay 22, and in full in chapter 5 of FREEDOM.

Jeremy Griffith’s biological explanation of why we became competitive and aggressive sufferers of the human condition when our conscious mind developed is, as mentioned, the subject of THE Interview, and fully explained in chapter 3 of FREEDOM.