Reproduced from Entrepreneur

(To read the article on the Entrepreneur website, either click on the above image or go to www.entrepreneur.com/en-au/news-and-trends/the-outsider-entrepreneur-of-ideas/498087.)

Entrepreneur’s 8 October 2025 article ‘Jeremy Griffith: The Outsider Entrepreneur of Ideas’:

The journey of Australian biologist Jeremy Griffith epitomises that entrepreneurial spirit. For fifty years, working independently of the scientific establishment, Griffith has pursued an audacious mission: to explain the human condition—why our species is capable of both profound love and devastating destruction.

______________________

Entrepreneurs live by forging new paths, but it takes boldness and persistence to turn a radical left field idea into something that truly changes the world.

The journey of Australian biologist Jeremy Griffith epitomises that entrepreneurial spirit. For fifty years, working independently of the scientific establishment, Griffith has pursued an audacious mission: to explain the human condition—why our species is capable of both profound love and devastating destruction.

Now, after decades of independence, his ideas are attracting recognition and support from leaders across the scientific community. One of the most prominent is Professor Harry Prosen, a former president of the Canadian Psychiatric Association, who described Griffith’s explanation as ‘the holy grail of insight we have sought for the psychological rehabilitation of the human race.’

Early Independence

Born in rural New South Wales, Griffith grew up immersed in the Australian countryside, nurtured, he says, by the unconditional love of his parents. According to Griffith, this early grounding gave him the emotional security and mental clarity that would later allow him to look into the most confronting of all subjects: our seemingly highly imperfect human condition.

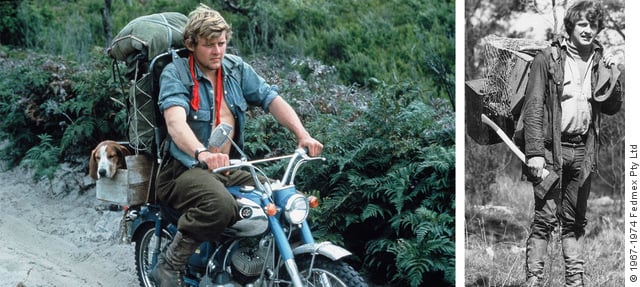

From early on, Griffith displayed the hallmarks of a force to be reckoned with. Along with first-class honours in biology, he also trialled for the national rugby team, the Wallabies, before taking leave to launch his first great project: an attempt to save Australia’s extraordinary marsupial wolf, the so-called Tasmanian Tiger or Thylacine, from extinction; the last captive one having died only thirty years before Griffith began his search in 1967.

The Quest to Save a Species

Forgoing a post-graduate scholarship at Stanford University, Griffith set out with little more than a trail bike and a hound dog he had trained to follow scent trails. Ingeniously, he built and deployed trail camera monitors throughout the Tasmanian wilderness to aid the search—pioneering a technique now common in wildlife research. His search became the most comprehensive field study of the animal, attracting international and Australian media coverage and backing.

Although he ultimately concluded the Thylacine was extinct, the project revealed classic entrepreneurial traits: innovation and resilience. Like inventors prototyping in garages before their ideas become mainstream, Griffith showed how self-sufficiency, vision and determination can push the boundaries that drive progress.

Starting Up

That same pioneering spirit found expression in commerce.

In late 1972, after returning from his Tiger expedition, Griffith began manufacturing furniture from natural bark-to-bark timber slabs—a design idea he pioneered that is now widely seen around the world. Starting with just a wheelbarrow to haul his first slab, he founded and grew Griffith Tablecraft into a thriving enterprise. By 1976, the business employed more than 40 people, operating from a 54-hectare property with a large pole-frame workshop that became a well-known tourist attraction in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales.

Jeremy Griffith established Griffith Tablecraft,

a thriving enterprise that became a well-known tourist attraction

What set Griffith’s furniture apart was its integrity. He insisted on designs that were free from nails, screws, glue, stain, or ornate embellishment—allowing the natural beauty of the timber to speak for itself. This uncompromising approach reflected what colleagues called his ‘clean thinking’, a quality that would also underpin his later biological work.

It was an entrepreneurial success story that demonstrated Griffith’s ability to spot opportunity, innovate, build a team, and scale a business—hallmarks of a bold mindset. For Griffith, however, independence and creativity were more than business ‘tools’; they were a way of life.

Even as Tablecraft flourished, Griffith’s attention was turning elsewhere. The clarity of thought that inspired his search for the Tiger and his uncompromising designs also drew him toward a larger challenge: making sense of humanity’s exploitative and excessive nature. Why do humans drive animals to extinction? Why do humans need excessive material comforts?

If he could strip away the embellishment in furniture to reveal the raw truth of the timber, why not strip away evasions in science to confront the raw truth about ourselves? That conviction and his training as a biologist set him on his most ambitious undertaking yet—explaining the human condition.

The Outsider’s Advantage

In pursuing a scientific explanation of the human condition, Griffith chose not to climb the academic ladder. Like a startup founder who forgoes corporate safety to pursue a risky idea, he struck out on his own. He believed that by attributing our destructive behaviour to ‘selfish instincts’, mainstream evolutionary science was avoiding the underlying truth: humanity’s original cooperative, selfless and loving moral sense and our now psychologically disturbed, or, as he terms it, ‘upset’ state.

Using the process of inductive reasoning championed by thinkers such as Charles Darwin and John Stuart Mill, Griffith concluded that this ‘upset’ arose from a clash within us—a conflict between our instinctive orientations and our conscious intellect. He asserts that when humans developed a conscious mind some two million years ago and began carrying out experiments in understanding, our instincts—unable to comprehend this new independent process—effectively condemned it.

Griffith illustrates this with a thought experiment. Imagine migratory birds suddenly endowed with human-like consciousness. While their instincts would still direct them along a precise, naturally selected flight path, their newfound conscious mind would compel them to question and explore. Those divergences would feel condemned by their instincts, which had been selected to resist deviation. To cope, the birds would become defensive, trying to justify their behaviour.

Griffith says humans experienced this dynamic. Over millennia, the effort to defend ourselves against instinctive criticism burdened us with guilt and defensiveness that hardened into the anger, egocentricity and alienation we now call the human condition.

Crucially, Griffith’s breakthrough doesn’t just account for our psychological turmoil—it points to how we can finally move beyond it. With understanding of why the intellect had to defy our instincts, he argues that the insecure, defensive angry, egocentric and alienated behaviours we have relied on are no longer necessary; they become redundant, and we are freed from the weight of the human condition.

Many argue that the reason Griffith could break such new ground is precisely because he worked outside established frameworks. As philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn observed in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, ‘Revolutions are often initiated by outsiders—people not committed to the dominant paradigm.’ Griffith’s independence, then, wasn’t a liability but one of the prerequisites that allowed him the freedom to ‘clean think’ humanity’s oldest riddle.

Ahead of the Curve

Griffith’s independence also gave him foresight. As early as 1983, he established the non-profit World Transformation Movement (WTM)—decades before the rise of today’s billion-dollar ‘Brain Initiatives’ and institutes for existential risk research. While governments and billionaire philanthropists continue to pour vast sums into mechanistic neuroscience, Prosen notes that Griffith was already building an independent, self-funded centre dedicated to explaining the true psychological nature of the problem of the human condition, further evidence of his self-reliance, tenacity and vision.

Persevering Through Adversity

But such independence came at a cost. Professor Prosen describes Griffith’s path in his introduction to Griffith’s main book, FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition:

‘Jeremy’s journey in bringing understanding to the human condition and protecting the integrity of that explanation—a 50-year saga—has certainly been a protracted and torturous one.’

Prosen explains that the resistance to Griffith’s work can be understood in psychological terms. For much of human history, the subject of the human condition has been too confronting for most humans to face. When a redeeming explanation is finally presented, it can trigger a deep, unconscious fear. Minds long protected by denial and defence mechanisms struggle to absorb the content, and people frequently misattribute their difficulty to flaws in the presentation, dismissing it as ‘dense’ or ‘confusing’. Supporters of Griffith’s work refer to this reaction as the ‘Deaf Effect’.

Prosen also notes that the fear triggered by confronting such a challenging subject often leads people to ‘fight back with a vengeance’, as they attempt to protect their denial-based defences. This dynamic helps explain why Griffith’s ideas, despite their biological accountability, liberating potential and growing scientific support, have faced vicious persecution—which in 1995 culminated in a defamatory media campaign against him and his supporters by two of Australia’s largest media organisations, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) and The Sydney Morning Herald. In an epic 15-year-long, ‘David and Goliath’ battle, Griffith, his eminent supporter, the twice-honoured order of Australia recipient Tim Macartney-Snape, and the WTM, sought redress—first from the Australian Broadcasting Authority, which censured the ABC and, ultimately, through the Australian Court systems in successful defamation actions against these two prominent media organisations.

Like Charles Darwin, who reportedly suffered from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) due to the strain of defending his theory of natural selection against entrenched opposition, Griffith endured CFS for a decade during his long battle against media persecution. Yet, off the back of his legal vindication, he and supporters of his work pressed on with the development and dissemination of what Prosen described as the ‘holy grail’ understanding of the human condition that enables ‘the psychological rehabilitation of the human race’.

Earning Scientific Respect

Although Griffith has faced fierce resistance from some quarters, over the years his work has also drawn striking endorsements across the scientific and academic communities. In addition to the psychiatrist Professor Prosen, who described Griffith’s explanation as ‘the holy grail of insight’, other distinguished voices have recognised the originality and profundity of his work including:

- Professor Stuart Hurlbert, the noted ecologist: ‘I am stunned & honored to have lived to see the coming of “Darwin II”.’

- Professor David J. Chivers, former president of the Primate Society of Britain: ‘FREEDOM is the necessary breakthrough in the critical issue of needing to understand ourselves.’

- Professor Scott D. Churchill, past president of the Society for Humanistic Psychology: ‘FREEDOM is the book all humans need to read for our collective wellbeing.’

- Professor Patricia Glazebrook, philosopher: ‘Frankly, I am blown away by the ground-breaking significance of this work.’

- Sir David Attenborough: ‘I’ve no doubt a fascinating television series could be made based upon this.’

Others have been equally emphatic. Clinical pharmacist Professor Karen Riley likened life without Griffith’s insights to living ‘back in the stone age’, while biologist Dr George Schaller judged the insights ‘fascinating and pertinent and must be disseminated.’

Together, these voices—spanning psychiatry, ecology, philosophy and public science—affirm that Griffith’s contribution is being taken seriously well beyond his outsider base.

The Entrepreneur of Understanding

Entrepreneurs create value by solving problems. Griffith has pursued a solution to the most challenging problem of all: rescuing humanity from its inner conflict. If his explanation is correct, the reward is far greater than any billion-dollar ‘unicorn’—it is the transformation of human life itself.

As Professor Prosen observed: ‘He is one of those incredibly rare individuals, a person of intellectual rigor and personal nobility who has the capacity to be completely honest without a personal bent…Jeremy is the most impressive person and courageous thinker I have ever met.’

For entrepreneurs, Griffith’s journey is a powerful reminder that the outsider’s path, though fraught, is often the one that changes the world.

(See https://www.entrepreneur.com/en-au/news-and-trends/the-outsider-entrepreneur-of-ideas/498087)