Griffith Tablecraft

Written by WTM founding member Genevieve Salter

Prior to and during Jeremy Griffith’s university studies, in which he gained a Bachelor of Science degree in Zoology from Sydney University in 1971, he undertook what is considered to be the most thorough search ever undertaken for the remarkable Thylacine, a marsupial wolf known as the Tasmanian Tiger—the last captive thylacine having died only 30 years before Jeremy’s search (see www.humancondition.com/tasmanian-tiger-search). While this search very sadly concluded that this astonishing animal had become extinct, during the search Jeremy was inspired by the occasional giant logs which the timber men called ‘single riders’ (one to a truck) that he saw while he was in the wilds of Tasmania. These immensely impressive giant logs led Jeremy to think, in his usual wonderfully enthusiastic way, how spectacular it would be to have table tops made from bark to bark slabs from these giant logs. While such complete bark to bark slabs or ‘flitches’ are now commonly seen in table and bar tops, no one was using such pure, unadulterated slabs of wood in furniture design in those days. Indeed, on his return from his final expedition to Tasmania in 1972 at the age of 26, Jeremy went to speak to specialists at the Wood Technology Centre in Sydney to seek their advice on his slab furniture idea and they laughed, saying that slabs of that width would warp. However, while sitting in their waiting room, Jeremy saw in one of their wood working journals pictures of a unique saw mill named Standard Sawmills located on the far north coast of New South Wales that was seasoning (drying) timber in slabs rather than in the usual cut down state. Undeterred by the Sydney experts, in December 1972 Jeremy hitch-hiked the 800 kilometres (500 miles) to the sawmill and spoke to the timber seasoning expert there, Peter Marshall, who it turned out was the world authority on the seasoning of hardwoods. Peter told Jeremy that as long as the seasoned slabs from their drying kilns were dressed the same on both sides he thought they would stay reasonably flat. So Jeremy walked across their timber yard and using a block and tackle pulled out the biggest slab he could see, purchased it, and transported it four kilometres (over 2 miles) on a wheelbarrow to a joinery shop where he had it planed and dressed. From this slab he made his first table in an abandoned truck shelter.

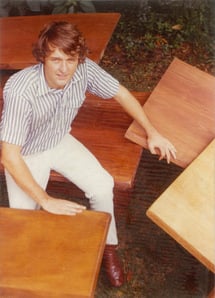

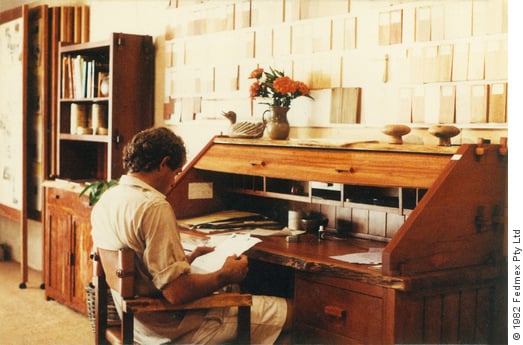

Jeremy in Sydney in Feb. 1973 with his first collection of

Griffith Tablecraft tables that he took to Sydney to sell

Over the next four years Jeremy worked on his simple, unadulterated designs and in 1976 he and one of his younger brothers Gervase, who came to help him in late 1973 after completing his journalist cadetship, had saved enough money to purchase a very beautiful 54 hectare property in the foothills near Murwillumbah in the Tweed Valley in northern New South Wales, where they established Griffith Tablecraft.

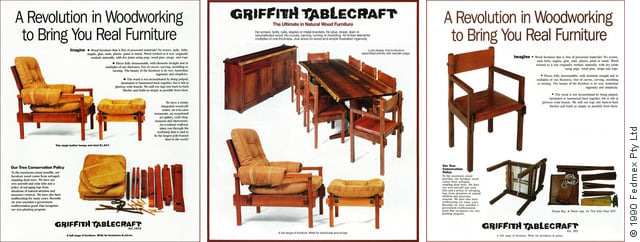

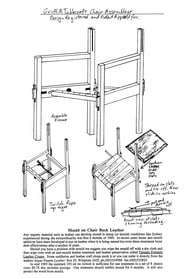

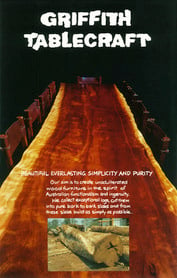

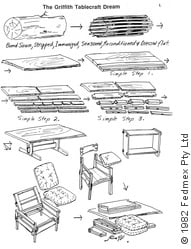

Jeremy’s vision was to create a range of furniture free from embellishment that highlighted the natural beauty and simplicity of the timber. The range was free of processed materials: no screws, nails or bolts, staples, glue, stain, plastic, paint or metal; no curves, moulding or turning; constructed using dry joints, wood pegs and pins, leather straps and twitched rope. All the pieces were fully demountable with all the elements in each piece being a multiple of the one thickness, which was the thickness of the slabs, as illustrated in the advertisements above.

4 minute video of Tim Macartney-Snape and Jeremy Griffith talking

about Jeremy’s furniture and demonstrating its simple construction

and the ease with which it can be demounted (taken from Part 2 of the

2009 Introductory Video titled ‘The World Transformation Movement’)

At the time that Jeremy was establishing the furniture business the Australian Government was offering grants to encourage people to create businesses, but when Jeremy applied they said he would have to locate the business in a conventional industrial estate. Jeremy wanted to be out with nature, so, fund-less, but with the help of a local bushman, Vic Bianchetti, who was proficient in using poles to build farm hay sheds, Jeremy designed a massive workshop with all the frame built out of timber poles, which was far less expensive to build than a conventional steel-framed shed. Since Australian eucalypt hardwoods are so strong, large all-pole-framed sheds have been built in Australia, but this one, when it was completed, was said to be the biggest ever (the roof poles all span 12.2 metres or 40 feet)! Vic and the other men building the shed, who you can see sitting on the rafters (there was no occupational health and safety in those days!) in the photo below (top left), were members of the Uki/Nimbin tug-of-war team (Uki and Nimbin are small towns near Murwillumbah) who were Australian National Champions for five consecutive years (see the bottom picture in the sequence of photos below), so they were very big men, which gives some idea of the immense scale of the workshop! Jeremy designed the building to be so large so there would be room for the huge flitches of timber to be stored. In time a solar kiln was built beside the workshop. A showroom and museum complex was also built nearby, and eventually an art gallery that Jeremy and Gervase’s mother Jill ran, and also a fully facilitated restaurant. From these buildings, which were also built from poles (centre left photo), a walkway extended up into the pole frame of the workshop so visitors could look down on the whole manufacturing process from the log to the finished furniture item (centre right photo).

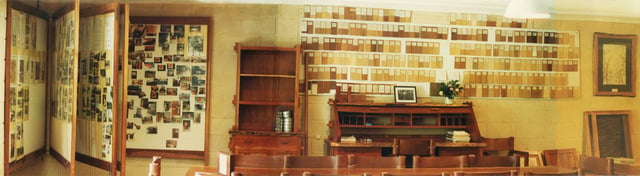

The showroom with display boards documenting each year’s progress and a wall of samples of all of Australia’s main sawmill timbers

The famous Uki/Nimbin tug-of-war team with some of their trophies. Vic Bianchetti, who was one of the finest and most loved men in the whole of the Tweed Valley, is second from the left in the bottom row. Vic was so admired that the Uki sportsground is named after him.

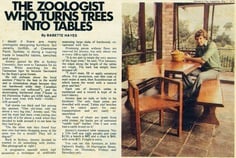

Jeremy’s ingenious designs were to gain much admiration and acclaim. Articles about the furniture featured in prominent Australian design magazines. Furniture was commissioned not only from private buyers but for commercial interiors, restaurant fit-outs, and even a chapel. Each table made was numbered and a piece of the wood kept as a record of these fabulously beautiful flitches of wood. By 1991, when Jeremy sold his share in the business to his brother Gervase, the Griffith Tablecraft Furniture Park had become a popular tourist destination with a staff of 45 people.

Read a selection of magazine articles in Women’s Day (7 May 1973); Craft Australia (1978); House and Garden (Nov 1983); and Belle: Interiors, Architecture, Decorating and Design (Jan/Feb 1985).

The Griffith Tablecraft showroom in the national trust gazetted building they owned at

201 Albion Street, Surry Hills in Sydney in 1982, with the natural carved solid brass sign

Jeremy made on the wall

Read or print

The Griffith Tablecraft Dream

As was explained about the idealism of the unresigned mind in the description of Jeremy’s search for the Tasmanian Tiger at www.humancondition.com/tasmanian-tiger-search, maintaining an uncompromised, honest, uncorrupted framework, as opposed to the compromised, artificial, dishonest framework of the ‘resigned’ world, was and has always been of paramount importance to every one of Jeremy’s unique undertakings (the psychological process of Resignation is explained in Freedom Essay 30). For Griffith Tablecraft that framework was encapsulated in a document Jeremy wrote in 1982 titled The Griffith Tablecraft Dream (shown on the right, which you can click on to read). This was a manifesto for the designs of the furniture and for the overall objective of the business, as this quote from it states: ‘at Griffith Tablecraft we want to bring in a new world, get the truth up, defy and help clean up the sea of denial, what Australians call bullshit, that surrounds humanity at present.’ It was displayed in the Griffith Tablecraft museum where it was bound in chains to emphasise the importance of maintaining Jeremy’s uncompromised philosophy at Griffith Tablecraft, as emphasised in the document’s last paragraph: ‘No one must be allowed to break these chains that hold our dream. In fact the reverse must happen—we must be helped and encouraged to hold onto our dream because then the truth, the world, and we, will truly win.’ It was only three years after starting Griffith Tablecraft that Jeremy realised that to be able to ‘defy and help clean up the [corrupt, artificial and superficial] sea of…bullshit that surrounds humanity’, and by so doing ‘bring in a new [soulful, sound, alienation-free, cooperative, selfless and loving, ideal] world’ he would have to solve the deeper issue of the human condition, find understanding of why we humans need to live in an artificial and superficial world that is so destructive of the natural world, and why we insensitively destroy animals like the Tasmanian Tiger—basically find understanding of why there is so much mad behaviour and human suffering in the world. And so in 1975 Jeremy began to enthusiastically write down his thoughts that he had long been having about what biologists refer to as ‘the human condition’ in the first fresh pre-dawn hours of every day before his furniture designing, manufacturing and marketing workday began—and this practice of writing in the early hours of the morning has continued to this day.

Incredibly, Jeremy eventually actually solved the human condition, ONE OF THE GREATEST FEATS IN THE HISTORY OF HUMANITY, thereby achieving the ‘Griffith Tablecraft Dream’ to ‘bring in a new world’ free of all the dishonest ‘denial’ ‘that surrounds humanity’—and thus ending the need for all the artificial and superficial embellishment and distraction that Jeremy was so committed to countering with his incredible, unadulterated furniture designs. He fulfilled the Griffith Tablecraft Dream of finding the means to fix the world, but appallingly, as will shortly be described, he was forced to continue the Griffith Tablecraft Dream without Griffith Tablecraft! You can read all about Jeremy’s fabulous resolution of the human condition at www.HumanCondition.com.

The following extract from paragraph 1227 of Jeremy’s 2016 book FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition sums up Jeremy’s vision for Griffith Tablecraft:

“Just to illustrate the change that is going to come to our old materialistic way of living, in front of me is a teaspoon—well, the monetary value of all the human-glorifying, egocentric content and effort that has gone into its ornate, embellished design, extravagant silver plating and competitive salesmanship and marketing to sell it to me, etc, etc, could feed a starving person for a week! Almost everything I see in front of me—my extravagant watch, my fancy shirt, my sophisticated pen—is in truth obscenely extravagant in a human-condition-free world. I should re-design all these items so they are not so extravagant, and it won’t be long before I and everyone else in the world will be doing just that. In fact, I idealistically once designed and manufactured a full range of wooden furniture that was free of embellishment and artificial content before realising that for such integrity to be tolerated the human condition needed to be explained. Imagine if all the car makers in the world were to sit down together to design one extremely simple, embellishment-free, functional car that was made from the most environmentally-sustainable materials, how cheap to buy and humanity-and-Earth-considerate that vehicle would be. And imagine all the money that would be saved by not having different car makers duplicating their efforts, competing and trying to out-sell each other, and overall how much time that would liberate for all those people involved in the car industry to help those less fortunate and suffering in the world. Likewise, imagine when each house is no longer designed to make an individualised, ego-reinforcing, status-symbol statement for its owners and all houses are constructed in a functionally satisfactory, simple way, how much energy, labour, time and expense will be freed up to care for the wellbeing of the less fortunate and the planet.” (FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition)

After Jeremy’s departure from Griffith Tablecraft, Gervase started introducing furniture designs that weren’t consistent with Jeremy’s unadulterated and uncompromised designs, and he completely changed the focus of Griffith Tablecraft from trying to end the corrupt state of the human condition to the hugely evasive, dishonest and pseudo idealistic goal of saving the environment, even changing the name to TreeTops Environment Centre! What a terrible betrayal of the Griffith Tablecraft Dream! (See Jeremy’s booklet Death by Dogma for a description of the deluded, escapist, human-condition-avoiding, extremely dangerous practice of pseudo idealism.)

Eventually, in 2002, Gervase sold the business and Griffith Tablecraft disappeared from the world!

The resurrection of Griffith Tablecraft

The above presentation mentions that Jeremy sold his share of Griffith Tablecraft in 1991. The reader may wonder why Jeremy would have sold his share in something that was so precious to him and so much part of his dream to ‘defy and help clean up the [corrupt, artificial and superficial] sea of…bullshit that surrounds humanity’, and by so doing ‘bring in a new [soulful, sound, alienation-and-suffering-free, cooperative, selfless and loving, human-condition-free, ideal] world’. Why were ‘the chains’ around ‘the Griffith Tablecraft Dream’ broken?

What happened was that Gervase, who had originally come to help support Jeremy’s inspired undertaking at Griffith Tablecraft, gradually started to try to take Griffith Tablecraft in his own directions, investing in real estate in the district, and even wanting to start a separate saw mill business, both of which had nothing really to do with the Griffith Tablecraft Dream; and, as mentioned, changing the focus of Griffith Tablecraft from trying to fix the corrupt state of the human condition to the utterly superficial, escapist and pseudo idealistic goal of saving the environment. Of course this hijacking of the Griffith Tablecraft vision distressed Jeremy immensely and he resisted it with all his might, writing reams of letters of appeal to all his family members to resist what Gervase was doing.

The problem that ultimately forced Jeremy to leave Griffith Tablecraft arose from their older brother John’s negotiation of the original partnership agreement between Jeremy and Gervase where Jeremy agreed he would not just give Gervase the 49% ownership of Griffith Tablecraft that Gervase asked for but an appreciative and encouraging full 50% half share on the basis, as John recorded in a 13 April 1975 document that summarised the agreement (see www.wtmsources.com/303), that Gervase ‘is quite prepared for final decisions in management to rest with you [Jeremy]’. What happened 15 years later in 1990 in a Griffith Tablecraft board meeting that John came down from Brisbane to participate in, was that John and Gervase ignored and violated the aspect of the agreement about the leadership of Griffith Tablecraft resting with Jeremy and instead focused on the fact that since Gervase owned 50% of the business Jeremy had no legal grounds to stop Gervase from what he was doing. Jeremy was utterly floored by their betrayal and emotionally shattered by what happened at that meeting.

And so Jeremy was shafted. He would not compromise his vision, and so he was forced to leave Griffith Tablecraft—although, as will be described shortly, he never really abandoned his Griffith Tablecraft Dream because he never stopped working to fix the world, and even the dream of making ideal furniture lives on.

The reader might wonder why John was so corrupt and brutal in his treatment of Jeremy, especially given his standing as a highly respected businessman having become Managing Director and CEO of the Australian Agricultural Company, one of the biggest agricultural companies in the world. The deeper reason for the ill-treatment of Jeremy by John and Gervase, and unfortunately also by their mother Jill who sided with them (this despite Jill’s incomparable core strength, soundness and idealism being the main source of Jeremy’s innocence and vision to defy the alienated world and end all the suffering of the human condition), is explained in WTM FAQ 2.5 where Jeremy describes how human-condition-confronting, truthful thinking prophets, which is what Jeremy obviously is (see FAQ 6.4 for more explanation of prophets), are typically initially rejected by not only the general public but even by their own family. In Jeremy’s case he experienced this rejection from almost all of the members of his family—his mother, his elder brother John and one of his younger brothers Gervase—but not from his youngest brother Simon who has always stood by Jeremy, basically starting the support movement for Jeremy’s undertaking of fixing the world, which is the World Transformation Movement. Jeremy’s father Norman had died in 1971 at the age of 57 in a tractor accident on the family farm near Guyra in northern New South Wales. You can read about how Jill’s wonderful core strength was Jeremy’s inspiration in Freedom Expanded in the part titled ‘How understanding of the human condition was found’, and Jeremy’s 2020 book How Laurens van der Post Saved The World contains further description of Jill’s inspiration for Jeremy’s work of solving the human condition.

In that FAQ 2.5 Jeremy cites the very great truth-telling, denial-defying, human-condition-confronting-not-avoiding prophet Christ’s experience of the problem, referring to Christ saying that ‘Only in his home town, among his relatives and in his own house is a prophet without honour’ (Mark 6:1-6). Christ must have also gone to hell and back emotionally standing up to his family’s ill-treatment of him. Obviously a prophet’s greatest love—and the essence of a prophet is their great love—is for their own family, yet, as explained in that FAQ, they are tragically the people least able to appreciate him. You will see in that FAQ how it is recorded in the Bible that ‘When his [Christ’s] family heard about this [his ministry], they went to take charge of him, for they said, “He is out of his mind” [gone mad]’ (Mark 3:21), and ‘mad’ is what Gervase was describing Jeremy as just prior to and after their break-up, even telling one of Jeremy’s most ruthless persecutors, Tom Biggs, who had come down from Brisbane to see Gervase to try to get ‘dirt’ on Jeremy, that Jeremy was ‘mad’. Interestingly, Christ made the obvious point when he was accused of being ‘possessed by...demons’ (Mark 3:22) and ‘out of his mind’, mad, for his ability to confront and redress the human condition, ‘How can Satan drive out Satan?’ (Mark 3:23), and ‘A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, and a bad tree cannot bear good fruit’ (Matt. 7:18). The Bible further describes how ‘even his own brothers did not believe in him [Christ]’ (John 7:5); and how ‘his own did not receive him’ (John 1:11); and how Christ was so ‘amazed at their lack of faith’ (Mark 6:6) that when ‘Jesus’ mother and brothers arrived [at a gathering and were]. Standing outside, they sent someone in to call him [Christ]. A crowd was sitting around him, and they told him, “Your mother and brothers are outside looking for you.” [Christ replied] “Who are my mother and my brothers?” he asked. Then he looked at those seated in a circle around him and said “Here are my mother and my brothers! Whoever does God’s will is my brother and sister and mother”’ (Mark 3:31-35). How defiant of ill-treatment and strong was Christ, as he had to be to defend his human-race-saving vision (see Freedom Essay 39 for Jeremy’s amazing description and explanation of Christ’s life, and it is an amazing demystification of Christ’s life, with many people saying it is ‘the best account and explanation of Christ I have ever read’).

So being thrown out of Griffith Tablecraft was a horrible, horrible experience for Jeremy, and a very great tragedy for the world—but all was not lost because, as mentioned, Jeremy never stopped working on presenting the understanding of the human condition needed to fix the world, AND ALSO BECAUSE JEREMY AND TONY GOWING AT THE WTM ARE EVEN GOING TO RESURRECT GRIFFITH TABLECRAFT! Hip hip hooray, soul/truth/love prevails, as it must if the human race is to be saved from self-destruction!

Tony Gowing, who is one of the authors of the WTM booklet The Great Transformation, is the leader of the Transformed Way of Living that understanding of the human condition makes possible; he is the St Paul-like promoter of a human-condition-resolved new way of living for the human race, and Tony has always loved both the vision behind Griffith Tablecraft and the integrity and ingenuity of the furniture. So in 2022, Jeremy and Tony came up with the plan to one day buy back the Griffith Tablecraft property and resurrect Griffith Tablecraft there, or, failing that, buy the pole shed Vic Bianchetti and his tug-of-war team built and transport it to a new site, or, failing that, build another fabulous all-pole shed for a new Griffith Tablecraft workshop and start manufacturing Griffith Tablecraft furniture again!

Already Jeremy and Tony have solved one of the design problems Jeremy was working on when he was thrown out of Griffith Tablecraft, which is the problem of the small wooden pegs that hold the front and back legs of the Griffith Tablecraft chairs coming loose and even breaking. Their solution, which they’re very excited about, is to extend the twitch rope method for holding the sides of the chairs together to also holding the legs onto the chair, as you can see in the two right-hand photos. Jeremy has sardonically said about the new design, ‘What a simple and obvious solution it is, and it only took 50 years to come up with!’

Left above and below: the previous peg and twitched rope design.

Right above and below: the new pegless twitched rope design

(cushion removed in the photo of the underneath of the chair).

So the ‘chains’ around the ‘Griffith Tablecraft Dream’ have been welded back together, and everyone should get hold of a ‘Sign Me Up Tony, Let’s Go’ to the new human-condition-resolved new world T-shirt!

What now needs to be documented is that the persecution of Jeremy didn’t stop after he was thrown out of Griffith Tablecraft. In fact, the persecution from the public at large of all his truthful, world-saving thinking began after he was dumped from Griffith Tablecraft, and those public media attacks were even more ferocious and brutal than the attacks from his family, if the utter horror of that can be imagined! But still Jeremy gave no ground to his attackers, and again prevailed against all those horrific attacks, winning condemnation of his attackers in what was described at the time as the biggest defamation case in Australia’s history, if the courage and brilliance of that can be imagined! You can read the summary of this other horrific saga in FAQ 3.17, and the more complete description in our Persecution of the WTM essay at www.humancondition.com/persecution.

To end this presentation, I should include another extraordinarily sound, denial-free, honest thinking prophet who, like Christ, recognised the problem of the resistance that anyone who dares to look into the human condition would receive, this time from the 360 writings of the great Greek philosopher Plato. Firstly, as to Plato’s greatness as a philosopher (philosophy being the study of ‘the truths underlying all reality’ (Macquarie Dictionary, 3rd edn, 1998)), A.N. Whitehead, himself one of the most highly regarded philosophers of the twentieth century, described the history of philosophy as being merely ‘a series of footnotes to Plato’ (Process and Reality [Gifford Lectures Delivered in the University of Edinburgh During the Session 1927-28], 1979, p.39 of 413). Yes, Plato, like Christ, was an extraordinarily honest, effective, prophetic thinker. Writing specifically about the all-important, human-race-saving challenge of ‘the enlightenment or ignorance of our human condition’ (and he used the term ‘human condition’), Plato warned that when someone tries to take humans out of the dark ‘cave’ where he said they have had to ‘take refuge’ from the ‘painful’ ‘light’ that makes ‘visible’ ‘the imperfections of human life’, that they ‘would much object’—even predicting that some ‘would say that his [the person who attempts to deliver understanding to the human condition] visit to the upper world had ruined his sight [they would treat him as mad], and that the ascent [out of the cave] was not worth even attempting.’ And I should mention that ‘not worth even attempting’ is what some of the WTM’s detractors have said projecting their own level of insecurity on the human journey to enlightenment, such as one of the architects of the media attacks on us, Charles Belfield, saying ‘You are encroaching on the personal unspeakable inside people and you won’t succeed’ (WTM records, 12 Feb. 1995). Plato continued, ‘And if anyone tried to release them and lead them up, they would kill him if they could lay hands on him’! (The Republic, c.360 BC; tr. H.D.P. Lee, 1955, or see the relevant section with quotes highlighted at www.wtmsources.com/227). Thankfully, we live in somewhat more civilised times, where truth-tellers now, unlike in Christ’s time, aren’t ‘kill[ed]’, but nevertheless the principle is clear: truth-tellers, even one like Jeremy who is presenting the redeeming, non-condemning, human-race-saving full truth about the human condition, are initially viciously persecuted, and so need to be extremely strong and determined to persevere, which is what Jeremy always is!

So, once again, you can read about this other horrific public persecution of Jeremy and the WTM in FAQ 3.17, and the Persecution of the WTM essay at www.humancondition.com/persecution. However, before reading those I do recommend you read FAQ 2.5’s more detailed and very interesting explanation for why prophets are not recognised in their own home.

See Jeremy’s remarkable search for the Tasmanian Tiger, and also

Jeremy Griffith’s artwork. For insights into Jeremy’s ability to grapple

with and solve the human condition, visit HumanCondition.com

and see for example Freedom Essays 49 to 51.