Jeremy Griffith’s Artwork

Written by WTM founding member Genevieve Salter

From simple, instinctive line drawings to visual masterpieces, this page is a small collection of the many artworks Jeremy has created over the years and describes where his creativity comes from. Jeremy is a biologist and naturalist, and the author of books, essays and videos explaining the human condition, but he is also a naturally talented and self-taught artist, designer and poet! Jeremy grew up in the sheltered environment of the Australian bush (you can read more about Jeremy’s background in his Biographical Profile) and his love of nature, our soul’s true instinctive world, fuels his creativity which in turn helps to preserve his soul. He has a truly unresigned, imaginative, enthusiastic, innocent approach to life (some of his school reports describe him as being ‘filled with a great zest for life’) which goes hand in hand with his selfless love for humanity and the determination that enabled him to get to the bottom of the problem of the human condition, humans’ contradictory nature, why we are capable of such great love and empathy on the one hand but are so ruthlessly competitive and selfish on the other.

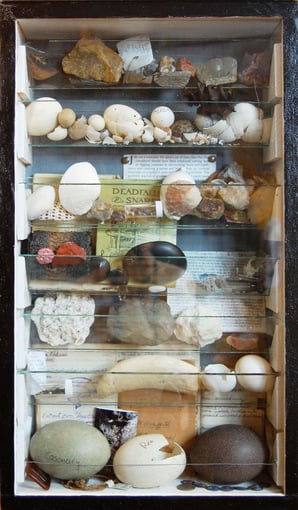

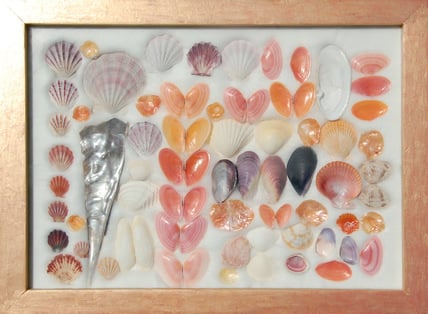

Jeremy is also an expert on birds and can imitate perfectly many of their calls. If you spend time with Jeremy talking about birds you find yourself suddenly aware of all the birds you can hear around you but for most of the time aren’t conscious of. He has wonderful collections of eggs, feathers, shells and butterflies among other artefacts and treasures collected in his boyhood and during his trips to Africa and throughout Australia. He has an extensive library of wildlife documentaries and loves to talk about and explain the behavioural traits of different animals, having made an exhaustive effort to save one of Australia’s most unique marsupials, the Tasmanian Tiger, from extinction, which he undertook when he was just 21 years old.

Jeremy’s time is never idle, he spends most of his days (and quite often nights) writing about the human condition, but on the rare occasions he is not working (and having no interest in the mind-numbing, artificial distractions of our resigned world—he can’t even type or text and he rarely watches films; as a young man, when he went to see Gone with the Wind at the cinema he had to get up and walk out because he was so upset by the main character, Scarlett O’Hara, using people to get what she wanted) he is thinking about a human-condition-free future for the human race, or creating useful tools for, and beautiful unpretentious, natural works of art to adorn, that wonderful new world.

To mark the awesomely exciting significance of 2013 for the WTM, and, in fact, for the whole world, with Jeremy having completed the first draft of his summa masterpiece book, FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition, and in celebration of the fabulous future for humanity that is now possible, Jeremy created this monumental sun from shells that he collected over a six month period from one small beach in Sydney. While cockle shells are found on sandy sheltered beaches throughout the world, Jeremy has never seen these pure gold-coloured ones on any other beach. Yellowish cockle shells are usually a rusty brownish-yellow colour, but on this particular beach some are a pure gold colour. Jeremy found the large white scallop shell on the same beach, and he’s never seen a large white one like this before or since. The white star limpet shells can be found on pretty well any beach. WTM founding members Tony Gowing and James West built and gilded the frame. If you look closely you can see the WTM initials made from shells at the top of the frame. The whole picture is positively bursting with excitement! To help fund the work of the World Transformation Movement, this artwork is for sale for $US5 million.

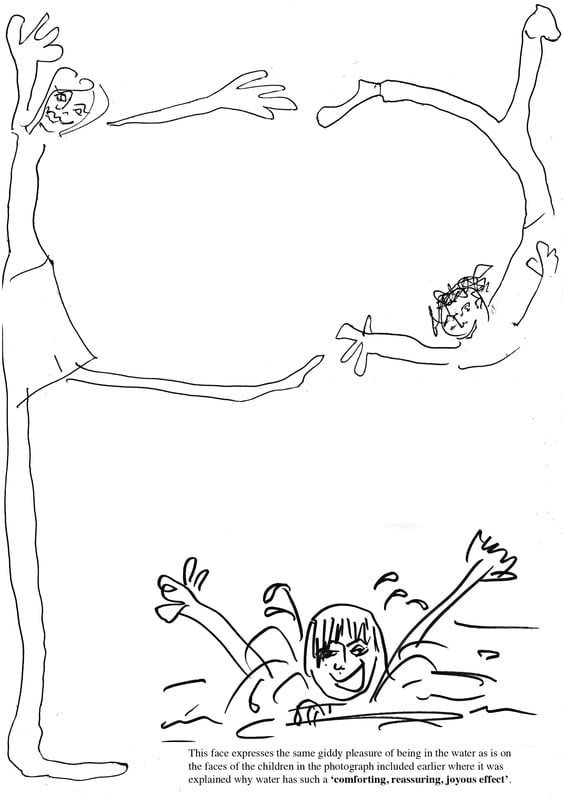

Incidentally, Jeremy believes that the lapping of water on the shoreline of sheltered beaches is especially therapeutic for humans. He explains that since we spend the first nine months of our lives in a fluid environment in the womb, the noise of moving fluid is something that for the rest of our lives we find comforting and soothing. He says that babies and children love playing in water because of this comforting, reassuring, joyous effect. To reduce the shock of being born into an air environment the practice of giving birth in the water is becoming increasingly popular. Jeremy has a plastic board on the wall of his shower and bath for writing on because so often good ideas come through when we’re in water. People often report that they came up with a great idea while in the shower or bath. Christians baptise their children in water, and there is a deeper reason for that, water is therapeutic. So Jeremy loves to walk along the shoreline to help him recover from the creative exertions of writing, hence one of the reasons for his fascination with shells.

Jeremy has long made these picture frames of objects he collected for presents by finding old frames and putting the objects on a layer of cotton wool. He also invented the box with V-shaped glass shelves for displaying items. Jeremy encourages parents to show their children how to make these display cases for all the wonderful things they find, although he now discourages collecting eggs and live butterflies!

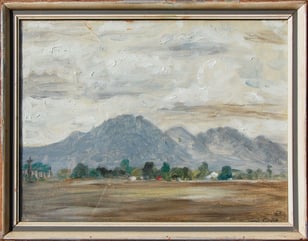

Paintings Jeremy did when he was at Geelong Grammar School (GGS) in 1963 when he was 17 years old. Left; watercolour painting of the golf course behind Cuthbertson House at GGS. Right; oil painting of the You Yangs mountains behind GGS. When Jeremy brought these paintings home from boarding school his mother had them beautifully mounted for the family living room.

When, in 2013, I rang Mr Gordon Griffiths who was the master who taught biology at Timbertop (the outward bound campus at GGS) when Jeremy was there in 1961, he said this: ‘I think of all the students that I ever had in my four years as a teacher at Timbertop that Jeremy would have been the one that I would have put as most outstanding, without a doubt [he said this with emphasis]…I can remember in the annual Up Timbertop and Back Race that he won the race, and in a record time, but he actually also collected a specimen, a lizard he hadn’t seen before, on the way back down! He was a brilliant bushwalker and a brilliant natural historian [Mr Griffiths also wrote in his school report for the year that Jeremy ‘has shown a very wide interest in natural history, more especially his interests are collecting butterflies and moths, identifying eucalypts and observing birds’]. And you know, he’s just one of these kids I would call a heart rebel [laughs]. I don’t mean that in a bad sense, that he was unpopular and a loner, because he wasn’t, he was very gregarious, but he had an independent spirit. Jeremy Griffith was sort of the cat that walked by himself, an independent type of person.’ Jeremy’s comment about this ‘independence’, which he said he wasn’t aware of, was that ‘when you resign you are not trying to think about the problem of the human condition, but when you haven’t resigned that is all you think about; you have a different agenda is how I would attempt to explain it.’ There is a similar comment in Jeremy’s 1958 report card from Tudor House School, a wonderful private boarding school that at the time was for boys near Sydney which Jeremy attended from 1955 to 1958. His house master (JM?) wrote that, ‘Jeremy sometimes tends to go his own way too much’. Jeremy was only 13 years old at the time so it’s evident that even at that young age his innocent mind had this ‘different agenda’ and was deeply engaged in trying to understand the resigned world.

As for Jeremy’s interest in nature, he had many collections to do with nature at Timbertop, one of which was of all the different animal scats/droppings so students could tell which animals were about. This extract from Australian author Steele Rudd’s On Our Selection reflects Jeremy’s love of the natural world, although, despite trapping a lot of rabbits and the liberal use of a catapult, he didn’t ever do anything as barbaric as Joe! ‘Joe was a naturalist. He spent a lot of time, time that Dad considered should have been employed cutting burr or digging potatoes, in ear-marking bears and bandicoots, and catching goannas and letting them go without their tails, or coupled in pairs with pieces of greenhide. The paddock was full of goannas in harness and slit-eared bears. They belonged to Joe’ (1899).

In 2021, when talking about his incredibly innocent, sheltered childhood and the possibility that he developed asthma as a child as a result of being so bewildered by the world when he first went away to boarding school at 9 years old, Jeremy recalled the amazing sensitivity of his parents, Jill and Norman Griffith, who always encouraged his interest in nature. As mentioned above, Jill had Jeremy’s landscape paintings from GGS framed for the living room wall, and when he had come home from Tudor House sick with asthma, Norman bought him a gold pan and an airgun. He also recalled his father taking the whole family out on the tractor with one of their workman, Harvey, who was part aboriginal, to find an eagle’s nest so that Jeremy could add an egg to his collection. Harvey climbed the tree and got right up under the nest but it was so big he couldn’t get around it to get to the top of the nest, about which Jeremy later said, ‘I’m pleased about now because it wouldn’t have been very nice to steal an eagle’s egg!’

I might mention that in 2014, despite the explanation of the human condition that is presented in Jeremy’s books being the fulfilment of the core vision of Geelong Grammar School of cultivating the sensitivity needed to achieve that specific, all-important-if-there-is-to-be-a-future-for-the-human-race task, the school chose not to include an essay on Jeremy’s life’s work that was commissioned by its publishers for possible inclusion in its Corio anniversary book 100 Exceptional Stories, which ‘celebrates the lives of 100 exceptional past students’. You can read the background to this at <www.humancondition.com/100-exceptional-stories>. Jeremy’s headmaster at GGS, Sir James Darling, who was described as ‘a prophet in the true biblical sense’ in his obituary in The Australian newspaper, would have been appalled at this omission—because as Jeremy has very clearly articulated in his various essays about Sir James’ life’s work, such as at <www.humancondition.com/darling>, Sir James’ great vision was specifically to nurture someone who could confront and solve the human condition, someone who ‘seeks truth at the bottom of the well’, and by so doing ‘saving the world’ (The Education of a Civilized Man, 1962, pp.64 and 140). This, as Professor Harry Prosen says in his praise of FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition, is precisely what Jeremy has achieved. Also, given how completely aware the school is of how horrifically persecuted Jeremy has been, they should have been amongst the first to promote his good work. Has there ever been a greater betrayal from people in the position of critical influence of a truly great life? Clearly, what needs to be added to what Christ said in the Bible, about ‘Only in his home town, among his relatives and in his own house is a prophet without honour’ should be the words ‘and in his school’!

Contrast these events with the comments from Mr Gordon Griffiths above. I should also include similar recognition of Jeremy’s character from Mr Eddie Coffey of Peribo Fine Books who distribute Jeremy’s books in Australia. Mr Coffey, who is regarded as a patriarch of the book industry in Australia, has known Jeremy for many years and in a letter to an overseas distributor in 2014, he described Jeremy as ‘one of the finest men I have ever met…with extraordinary ideals’. In correspondence with Sir Laurens van der Post’s daughter Lucia, who is herself a well-known writer, she also referred to Jeremy’s ‘wonderful enthusiasm’ and ‘wonderful, wonderful book’; and the highly esteemed ecologist Dr Stuart Hurlbert, who is Professor Emeritus of Biology at San Diego State University, has said about Jeremy and his work, ‘I am stunned & honored to have lived to see the coming of “Darwin II”’.

Sir Laurens suffered similar persecution of his life and work; this occurred despite King Charles choosing Sir Laurens to be godfather to his eldest son and future king, Prince William. There is ‘A bronze bust of van der Post…in Prince Charles’ garden at Highgrove’ (‘Post, Sir Laurens Jan van der (1906-1996)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Christopher Booker, 2004). Former British Prime Minister, Baroness Thatcher, once described Sir Laurens as ‘the most perfect man I have ever met’ (mentioned in J.D.F. Jones interview on Late Night Live, ABC Radio, 25 Feb. 2002), and Sir James Darling himself wrote that ‘In the world of books there are, for me, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, or Laurens van der Post’ (The Education of a Civilized Man, ed. Michael Persse, 1962, p.36 of 223).

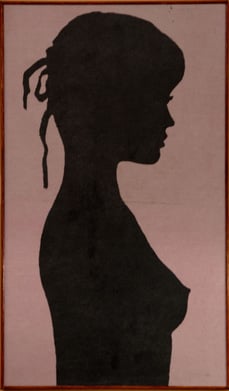

Carving of a young woman’s face Jeremy made with his pen knife on a piece of

stone he found in the back paddock of the family’s 3,500 acre sheep station called ‘Totnes’ near

Mumbil in Central West NSW in 1964 when he was 18 years old.

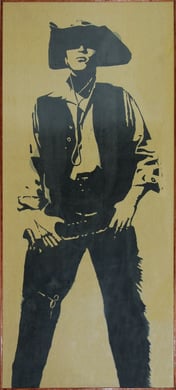

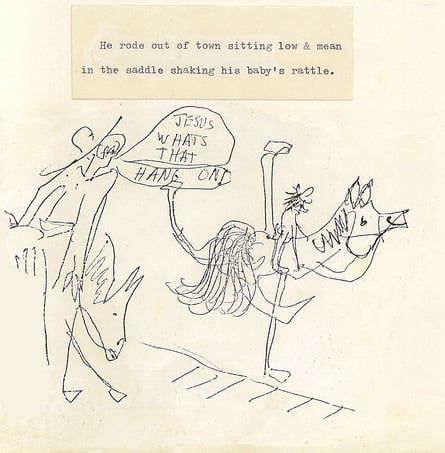

Screen prints made whilst at university in 1967. While Jeremy drew the print on the left,

the cowboy image on the right he copied from the cover of a book titled Born of the Sun.

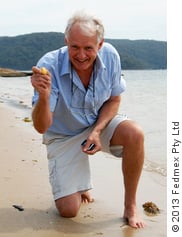

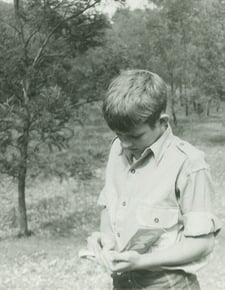

Jeremy in Dec. 1967 on his 22nd birthday, the day before setting off

for Tasmania with his hound dog Loafy to commence his Tiger search.

One of Jeremy’s favourite artists is the aboriginal painter Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Emily’s astonishing ability to express pure beauty comes from her unimpeded access to her soul (our species’ fully cooperative, all-loving and all-feeling original instinctive self). Emily lived in the desert country of central Australia and didn’t see a white person until she was 16, and only started painting when she was 80! Jeremy recreated one of Emily’s paintings because he loved them so much and couldn’t afford to buy one. He acknowledges this at the bottom of the painting by calling it a ‘Jemily’. It can be seen on the wall in the background of many of the videos on our website.

Watch the above short video of Jeremy painting his ‘Jemily’ and explaining the

beauty and significance of Emily Kngwarreye’s work in 2009.

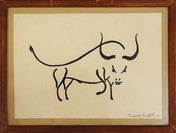

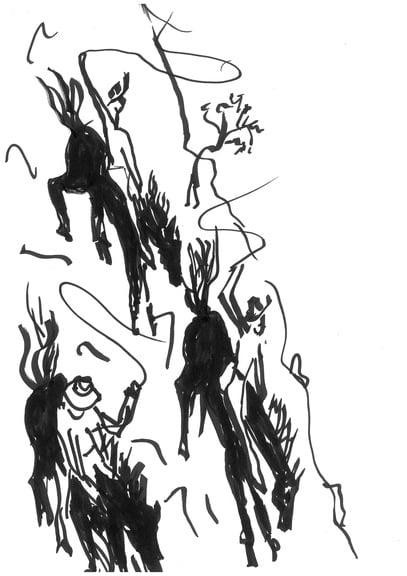

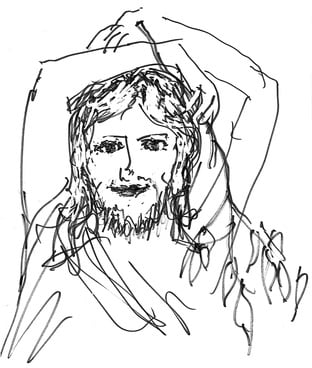

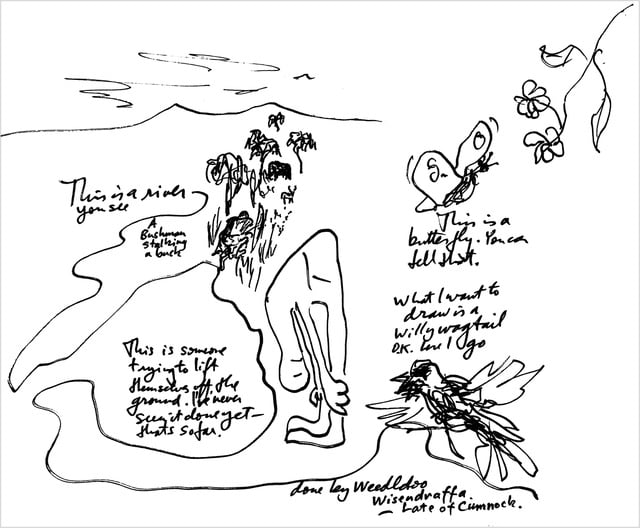

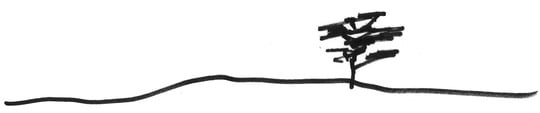

These are two of the many instinctive line drawings Jeremy uses throughout his books. You can see many more of Jeremy’s amazingly effective line drawings that he uses to illustrate aspects of the human condition in his 2022 book The Shock Of Change. The following extract from Freedom Expanded: Book 1 explains these drawings and where humans’ creative powers come from:

“I find the extreme sensitivity that is particularly apparent in the rock paintings of the Bushman of southern Africa and Australian Aborigines, and in the cave paintings of early humans in Europe, especially revealing of how much innocence the human race has lost in relatively recent times. In order to draw the little pictures that have been included throughout this written presentation, I learnt long ago that I have to disconnect my conscious mind and just let my instinctive sensitivity express itself, and that if I don’t do that I simply can’t draw at all. For example, the drawing of the three childmen happily embracing that I used to illustrate humanity’s Childhood stage earlier [shown above] was done so quickly I shocked myself because I could hardly believe that such an empathetic drawing could be produced from an almost instant scribble. At that moment I saw just how much sensitivity we once had, and how much alienation now exists within us two-million-years-embattled humans. The extraordinary empathy and accuracy of the paintings of animals in the rock and cave paintings I referred to above are similarly incredibly revealing of the amount of sensitivity we humans once had and have since lost. We are such an embattled species now, so worn out, so brutalised, so toughened. How extremely sensitive must early humans have been! Sir Laurens van der Post wasn’t exaggerating when he wrote that ‘He [the Bushman] and his needs were committed to the nature of Africa and the swing of its wide seasons as a fish to the sea. He and they all participated so deeply of one another’s being that the experience could almost be called mystical. For instance, he seemed to know what it actually felt like to be an elephant, a lion, an antelope, a steenbuck, a lizard, a striped mouse, mantis, baobab tree’ (The Lost World of the Kalahari, 1958, p.21 of 253)…It is truly an insight into how sensitive and loving we humans once were that our instinctive self or soul can’t relate to the way we humans are now. Consider the tenderness in the expression on the face of the Madonna in the drawing of the Madonna and child that was included at the beginning of the Infancy stage in Part 3:11A [shown above]. My soul drew that—I, my conscious self, had nothing to do with it. Truly, as William Wordsworth wrote, ‘trailing clouds of glory do we come, From God [the integrated, loving, all-sensitive state], who is our home’ (Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood, 1807). And people say we humans have brutish, aggressive instincts! It’s the world we humans currently live in that is mad. It is just so traumatised with upset that it hasn’t been able to deal with the fact that it is deeply, deeply dishonest, horrifically alienated. What did the great Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), one of the modern world’s most accomplished artists, famously say about his ability to paint: ‘It’s taken me a lifetime to learn to paint like a child.’ And what did R.D. Laing say, ‘between us and It [our true self or soul] there is a veil which is more like fifty feet of solid concrete’…Similar to what happens when I draw, in my writing I have also learnt to, as I describe it, ‘think like a stone’, or ‘think like a child’—say the simplest, most elementary thought—because I learnt that such a thought will be the most truthful and accurate and accountable and explanatory. Absolutely every time I encounter a problem I have to solve in my thinking about the human condition I go into a routine where I say to myself, ‘Just go into yourself and think like a stone, just let the truth come out that’s within and you will have the answer.’ Basically, I learnt to trust in and take guidance from my truthful instinctive self or soul. I learnt to think honestly, free of intellectual bullshit, and all the answers, all the insights that I have found, and there are many hundreds of them, were found this way. Indeed, I know every sentence I write is truth-laden, in complete contrast to the millions of sentences being churned out every second everywhere else on Earth. It is the innocent instinctive child in us that knows the truth. As usual, Christ put it perfectly when he said, ‘you have hidden these things from the wise and learned, and revealed them to little children’ (Matt. 11:25). Albert Einstein also recognised the mental integrity of the young when he famously said that ‘every child is born a genius’; the American architect and philosopher Richard Buckminster Fuller similarly said, ‘There is no such thing as genius, some children are just less damaged than others’ (NASA Speech, 1966), and ‘All children are born geniuses. 9999 out of every 10,000 are swiftly, inadvertently de-geniused by grown-ups’ (Education for Human Development: Understanding Montessori, by Mario M. Montessori Jr., Paula Polk Lillard & Buckminster Fuller, 1987, Foreword); while R.D. Laing noted that ‘Each child is a new beginning, a potential prophet [denial-free, honest, truthful, effective thinker]’ (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, 1967, p.26 of 156). Laing also pointed out that ‘Children are not yet fools, but [by our treatment of them] we shall turn them into imbeciles like ourselves, with high I.Q.’s if possible’ (ibid. p.49). Sigmund Freud was another who recognised the problem of the alienated adult/modern human mind, writing, ‘What a distressing contrast there is between the radiant intelligence of the child and the feeble mentality of the average adult’ (The Freud Reader, ed. P. Gay, 1995, p.715). Many exceptionally creative people have made statements to the effect that genius is the ability to think like a child. As just mentioned, one of the most accomplished artists of all time, Pablo Picasso, famously said (about his struggle to paint well) that ‘It’s taken me a lifetime to learn to paint like a child.’ Truly, our species’ original instinctive self or soul, which the innocence of children still has access to, is wonderfully orientated to the cooperative, integrative, ‘Godly’, loving, ideal, truthful state. We do indeed come ‘trailing clouds of glory…From God, who is our home’. Interestingly, a comment that was included earlier, by the biographer George Seaver on the theologian, missionary and physician Albert Schweitzer, reiterates what I have just said about natural thinking: ‘Naturalness. That is the keynote of Schweitzer’s thought, life, and personality. The ultimate thought, the thought which holds the clue to the riddle of life’s meaning and mystery, must be the simplest thought conceivable, the most natural, the most elemental, and therefore also the most profound’ (Albert Schweitzer The Man and His Mind, 1947, p.311). (Part 3:11C Adventurous Adolescentman of Freedom Expanded: Book 1)

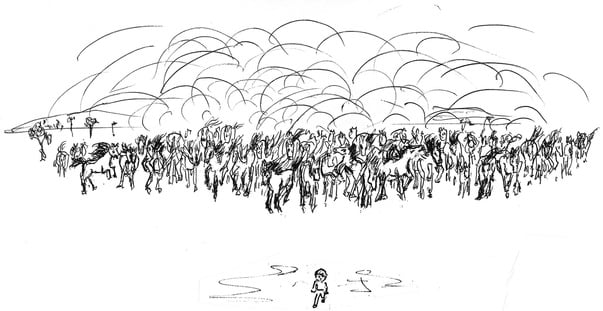

Jeremy’s 1995 drawing of horsemen galloping down a steep impasse, inspired by

revered Australian poet Banjo Paterson’s 1890 poem The Man from Snowy River.

An acacia tree on the horizon drawn in 1998. The simplicity of the drawing

evokes our instinctive memory of Africa—our soul’s home.

Jeremy’s 2004 drawing of Jesus Christ as someone completely free and natural.

In 1972, whilst still in Tasmania Jeremy wrote in a letter to a girlfriend these words: ‘Playing saying seeing dreaming you left me with a funny feeling! I won’t study so I will try and write to you. I feel like writing because it’s cloudy. There were a thousand wild horses out on that great plain and before them strode a boy and he was alone and hopelessly happy’. Accompanying the letter was the above drawing. In Freedom Expanded: Book 1 Jeremy writes: ‘I can understand now that this image of the horses and boy was a representation of my vision of my innocence being able to lead humanity home from its alienated state. In fact in every major document I have written I have included a phrase that has always summarised my vision, which is that “soon from one end of the horizon to the other will appear an army in its millions to do battle with human suffering and its weapon will be understanding”’.

Jeremy drew this picture in 1998 for a friend who was

starting an aged care business to use on a flyer.

Jeremy said of the drawing above, which he drew for Freedom Essay 60 about the world-destroying crime of ‘Ships At sea’ ‘Pocketing The Win’ when we desperately need to get these understandings to the world, ‘the person from the collapsed city is spread eagled on the ground, just like the tree is beside him, both humanity and nature dead as a result of our egocentricity, how good’s that for an intuitive little drawing!’

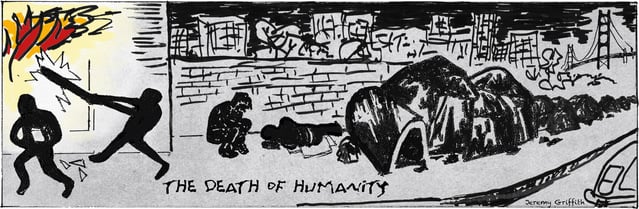

Jeremy’s drawing ‘Dogma leads to the dystopia of lawlessness, unbearable

psychosis and homelessness’, drawn for his 2021 book Death by Dogma

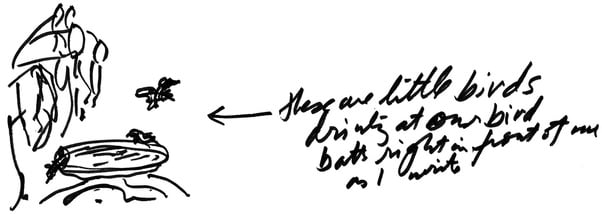

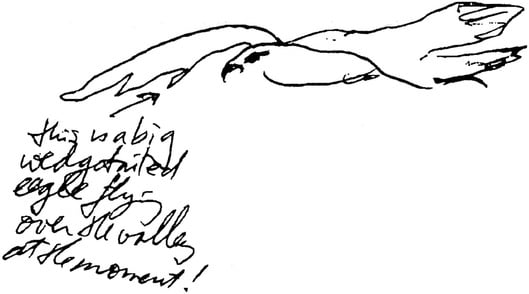

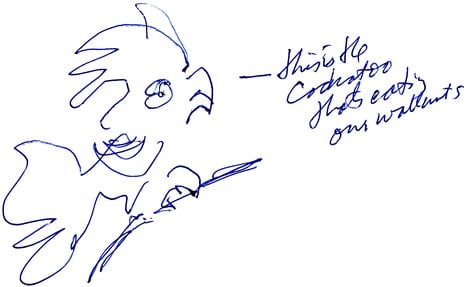

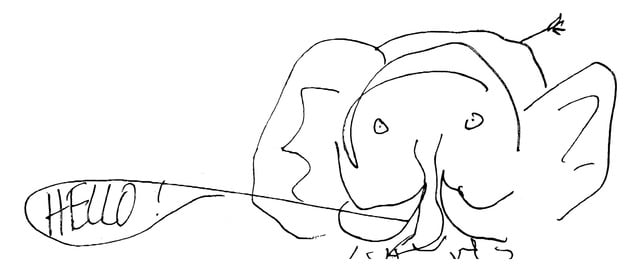

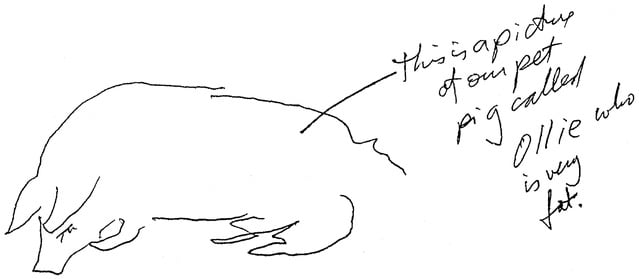

As mentioned above, Jeremy loves birds and can imitate many of their calls, so of course he loves to draw them too! Above and below are some examples that his partner Annie Williams collected over the years as often he would draw them on the bottom of letters to their friends.

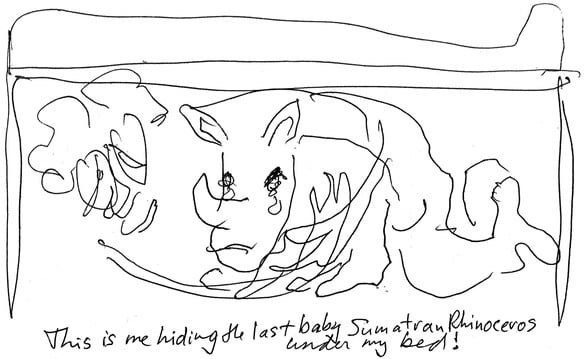

…and not only birds but other animals as well.

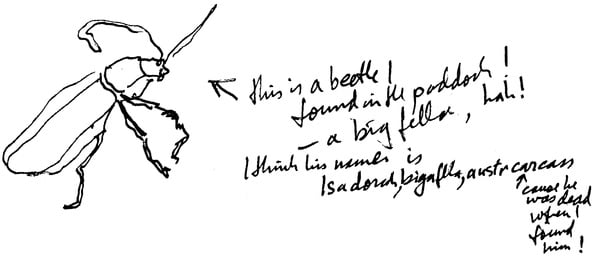

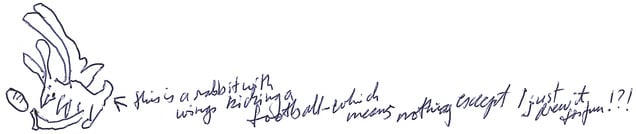

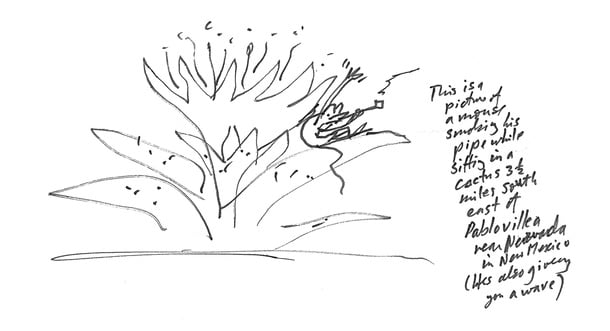

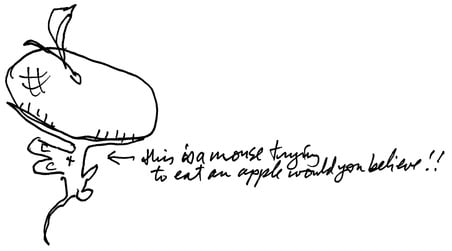

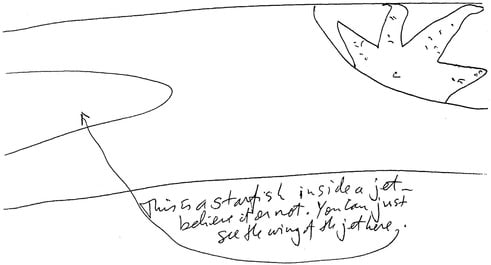

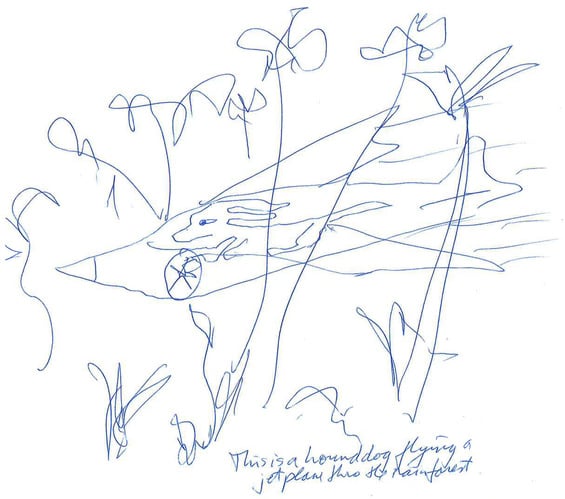

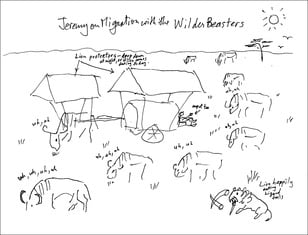

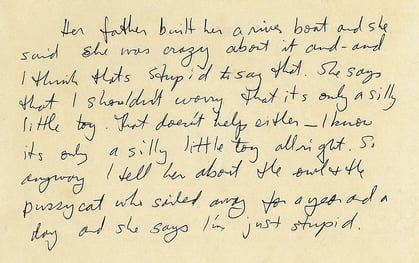

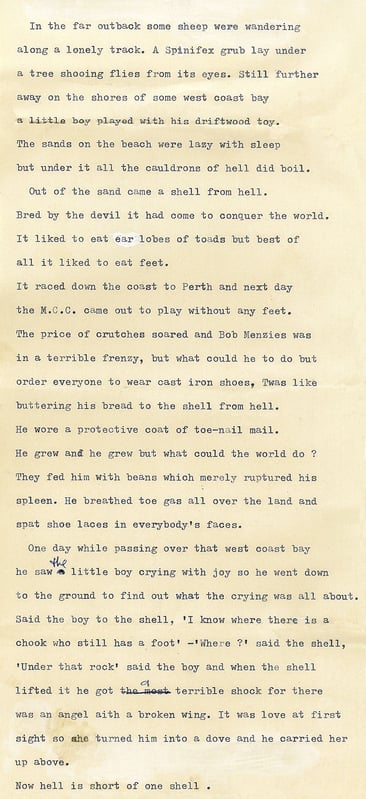

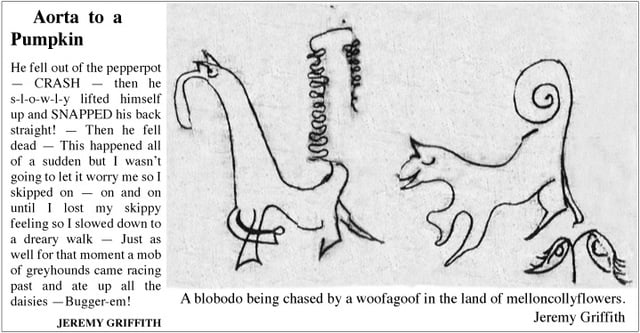

Another of Jeremy’s ingenious creations are his ‘Ultra Nothing’ drawings and poems—a way of giving the soul free reign to express itself in silly and imaginative ways. He began writing and drawing Ultra Nothings in his university days and he’s still doing them today! Rarely does he write a personal letter that does not include a drawing of some kind—a starfish inside a jet or a mouse trying to eat an apple as seen below! He refers to these Ultra Nothings in his 1967-68 document What I Reckon! which he carried with him whilst in Tasmania searching for the Tasmanian Tiger. John Lennon’s books In His Own Write (1964) and A Spaniard in the Works (1965) are marvellous examples of Ultra Nothings, and Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s wonderful (because of its honesty about the resigned adult world) children’s book The Little Prince contains similar Ultra Nothing sensibilities.

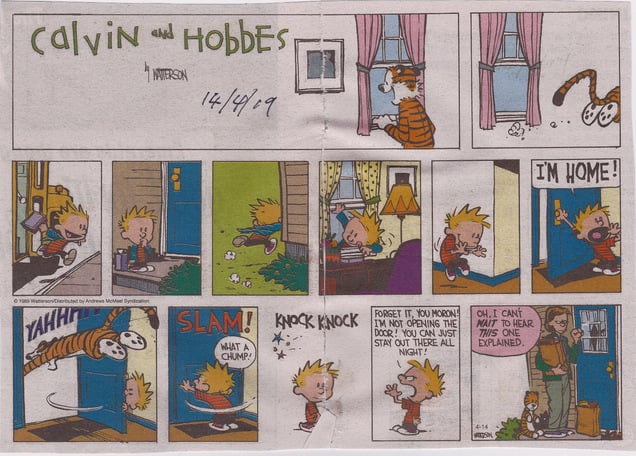

Jeremy also loves the famous Calvin and Hobbes cartoons drawn by Bill Watterson who Jeremy says “is like JD Salinger, people try to find him but they say he’s as elusive as ‘Bigfoot’!...He only did the cartoons from 1985 to 1995 and has refused to do any more since. You do get the feeling that it’s a bygone age, a time when homes were functional rather than dysfunctional, but they’re apparently so beautiful they’re still being syndicated everywhere around the world. Did you see the Calvin cartoon today, it was just so heartbreakingly beautiful how Calvin has this imaginary friend which is his tiger toy called Hobbes. Hobbes sees Calvin coming home from school and is so excited, and Calvin, when he gets to the front door, thinks ‘I’ll play a trick on him’, so he goes around and climbs in the window and then pretends he’s just arrived at the front door and says ‘I’m home!’ and when Hobbes comes hurtling to greet him, he lets him through and then shuts him out, as naughty six year old’s will do, and then his mum comes home and sees his stuffed tiger sitting on the front doorstep and says to herself, ‘oh dear, it’ll be very interesting to find out what’s happened in Calvin’s world to cause this excommunication’!!!!!!”

One of Jeremy’s ‘Ultra Nothings’ published in the

University of New England student newspaper, Nucleus, in 1967.

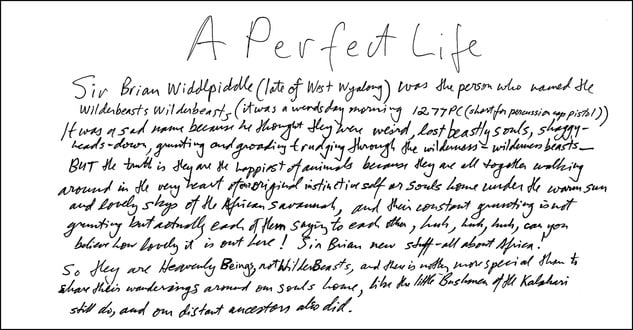

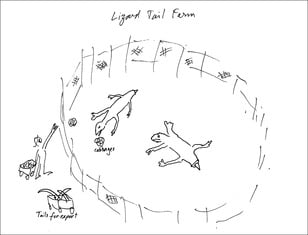

Jeremy’s 2011 book for children, A Perfect Life, describes the farming of giant lizards who can re-grow their tails so these tails can be fed to lions and other predators so they no longer have to kill their animal friends! You will note Jeremy can’t spell, he has never been able to spell and still can’t. He says he couldn’t care less about spelling. Academically, Jeremy says he was a train wreck, usually coming last or close to last in his class.

This is a very entertaining little video of Jeremy explaining A Perfect Life. It’s a funny story but provides an example of how sensitive our thinking will be in the human-condition-free new world and how we will put our minds to ways we can help each other and the natural world, like feeding cabbages to lizards and harvesting their tails to feed to the crocodiles so they don’t eat the wildebeests! There is a beautiful passage in paragraph 840 of FREEDOM about the conflicts that our sensitive soul knows exist in nature and how many animals, like crocodiles, struggle to be loving, and how magnanimous our soul’s world is towards this sometimes divisive behaviour and that we will want to find ways to help. A Perfect Life is also the subject of Freedom Essay 52.

With regard to Jeremy’s ability to draw, his great-grandfather on his father’s side was a church canon who came out from Ireland to Australia, and whose ancestors came from Wales in the latter half of the 1600s during The Plantations period. His surname was Bevan and he was known as ‘Canon Bevan’. Well, Canon Bevan was said to be a wonderful drawer and to have a very funny, entertaining sense of humour. So it could be that Jeremy got his ability to draw from his great-grandfather, although, as Jeremy described earlier, he attributes it to his relatively innocent access to our species’ instinctive self or soul. Jeremy can certainly draw and, as can be seen in his Ultra Nothing drawings, he has a wonderful sense of humour as well. Often, during breaks from his writing which requires incredibly intense focus, he is telling jokes and funny stories to make us all laugh and help relieve the pressure of our difficult job. He is quite a good yodeller as well which is very entertaining—and he can roll a coin through his fingers, and spin a coin right along a bar at the pub so that it goes around a glass of beer and comes back again! Jeremy has this extraordinary free, unresigned mind, the result of which is he is extremely imaginative, so his sense of humour, like his ability to draw, is probably a product of genes and nurturing. Jeremy’s great interest during his school years was nature and although he was a gifted sportsman he never won any academic prizes. When he was at Tudor House School, however, he did, on more than one occasion, win the prize for ‘Most Amusing’ (Jeremy explains that in the school’s annual fancy dress party, he twice went as ‘The World Famous Irish Tin Can Band’, which anyone who couldn’t think of what to go as could join, and the band marched around the room crashing together garbage lids and the like, making so much noise he was given this prize to shut him up!). Also, the 1958 edition of the school magazine published an imaginative story Jeremy wrote when he was 12 about a pet cockatoo who would blow rice bubbles through a straw and yell ‘stick ’em up’, and that one day a burglar entered the house and the cockatoo held him up until the police came! Anyone who was at the University of New England with Jeremy will tell you stories of Jeremy sitting at the back of the class drawing funny pictures, like ‘A person eating his forehead’, and passing them around the lecture theatre. It’s little wonder Jeremy loves the irreverent Irish stand-up comedian Tommy Tiernan. He says Tommy’s ‘childlike irrepressibility is such sweet, sweet relief, he’s got the laughingest eyes you’ve ever seen, they’re so clear and sparkly, they’re just like something out of heaven’.

A few of the recent (July 2019) funny text messages Jeremy regularly sends include this he sent to James Press after he’d added some more footage to one of the Introductory videos on our homepage, ‘I just watched it pretending I’d never seen it before and I thought “shit, that’s bloody amazing”, so that’s good objective feedback’; and to Tony Gowing to try to get him to look after himself as he works so hard and so selflessly for this project, ‘Tone, if you don’t put one of those air conditioners in your room I will never speak to you again, and I’ll send you nasty text messages every second day, or maybe every day, I haven’t worked that bit out yet’; and to Damon Isherwood and Fiona Cullen-Ward who are part of the WTM Publishing team, ‘Accepted your edits Damo & Fi…Your well intentioned and most appreciative friend, Calvin (you can see me in a comic strip in The Telegraph [see a Calvin cartoon included above] every day, where you will see that I’m very cute)’; and to Jοhn Bіggs and his partner Εmmα Cullen-Ward before a well-earned break, ‘Dear John and Em, Godallfuckingmighty I hope you guys have just the most wonderful adventure the world has ever seen, I hope you have just so much fun and see just so many wonderful things you will not even be tempted to scoff a whole bucket of ice cream even [John’s favourite food!], godallfuckingmighty I hope you have a good trip, yours sincerely Bert from Walgett’.

The caption that appears below this photograph in paragraph 835 of FREEDOM further illustrates Jeremy’s very funny and imaginative mind—and also his unresigned mind’s great preoccupation with trying to understand the world.

Annie Williams and I in Samburu National Park in Kenya in 1992. Those giraffes behind us

are just walking around as free as a daisy. In natural Africa, animals like giraffes and elephants

and rhinoceroses (well, terrifyingly, there are actually almost no rhinos left!) aren’t in cages; there

are no fences over there. Animals—and the place is teeming with them, all sorts of weird shapes

and sizes—just walk all around the place. It’s amazing. They can go wherever they want. They can

stop here for a while and then go over the hill if they want to. They just mooch about everywhere;

walk around a bush and there is another one, this time with great spiral horns coming out of the top of

its head, big eyes looking at you as if to say, ‘So, who are you, what’s your problem?’ ‘My problem!

Have you had a look at what’s coming out the top of your head!?’ It takes some getting used to I can

tell you. I don’t know who made them all, and was he just having fun making them all in such

weird and different shapes—and, more to the point, who let them all out!

I wanted to also include mention of Jeremy’s Welsh ancestry, which I touched on earlier. A 2023 documentary titled Who Are The Welsh? presented by YouTuber and author Kevin MacLean, ends by saying, ‘The need for [King] Arthur’s return couldn’t be greater, and I’ll be watching for him’, and a similar sentiment is expressed at the end of the classic 1941 film about a Welsh mining town, How Green Was My Valley, with the main character, whose name is Mr Gruffydd/Griffith, (‘Griffith’ being a Welsh name) saying, ‘I thought when I was a young man that I would conquer the world with truth. I thought I would lead an army greater than Alexander ever dreamed of, not to conquer nations, but to liberate mankind with truth.’ These quotes attest to the deep awareness in the world that, because of their remarkable historic resistance to, and isolation from, the on-rush of the exhausted human condition everywhere else in the world, that the Welsh have retained enough soundness and strength of self to look into the most difficult of all subjects of the human condition, and find the yearned-for redeeming ‘truth’ about our deeply troubled condition. They support a belief in the great druid prophesy that King Arthur, and Llywelyn ap Griffith (who was the most famous of all Welshmen and the only native King of Wales to be recognised by the English), will one day return to ‘liberate mankind with truth’. In solving the human condition, Jeremy’s work undoubtably represents such a return—you could say, the return of the true King from Wales! Griffith is a common name, and while the unconditional love Jeremy received from his mother and the saintly character of his father would, in large measure, account for his soundness and courage, there does appear to be evidence of this Welsh bold and adventurous strength in Jeremy’s genetic heritage which must have also been influential. You can read more about the Welsh Arthurian mythology, and Jeremy’s ancestry in paragraphs 1036-1037 of FREEDOM.

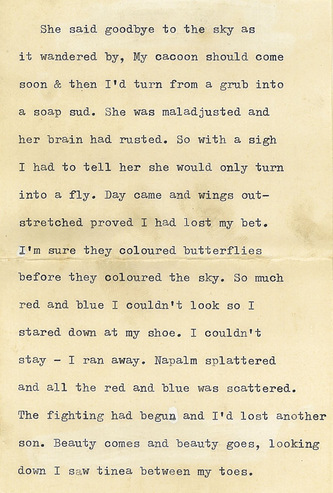

This poem of Jeremy’s, written in about 1969 when he was 23 years old, is a powerful anticipation of our species’ liberation from the human condition and reveals how alive and irrepressible his soulful world is. It also shows how strong Jeremy’s vision has always been of being able to solve the human condition and by so doing bring about a fabulous human-condition-free new world for humans. It is reproduced in FREEDOM, chapter 9:11 The ‘pathway of the sun’:

‘This is a story you see, just a story—but for you / Um—I remember a long time ago in the distant future a timeless day / a sunlit cloudless day when all things were fine / when we all slow-danced our way to breakfast in the sun // You see the day awoke with music / Can you imagine one thousand horses slow galloping towards you across a vast plain / and we loved that day so much / We all danced like Isadora Duncan through the morning light // We skipped and twirled and spun about / Fairies were there like dragonflies over a pool / Little girls with wings they hovered and flew about / their small voices you could hear / You see it was that kind of morning // When the afternoon arrived it was big and bold and beautiful / In worn out jeans and bouncing breasts we began / to fight—our way—into another day / into something new—to jive our way into the night / from sunshine into a thunderstorm // We all took our place, rank upon rank we came / as an army with Hendrix out in front / and the music busted the horizon into shreds / By God we broke the world apart / The pieces were of different colours and there were so many people / We danced in coloured dust, we left in sweat no room at all / We had a ball in gowns of grey and red / There were things that happened that nobody knew / Bigger and better, I had written on my sweater / Where there was sky there was music, huge clouds of it / and there were storms of gold with coloured lights / It was so good we cried tears into our eyes / In a tug of war of love we had no strength left at all / Dear God we cried but he only sighed and / whispered strength through leaves of laughter // On and on we came in bold ranks of silvered gold / to lead a world that didn’t know to somewhere it didn’t care / It couldn’t last, it had to end and yet it had an endless end / We were so happy in balloons of coloured bubbles that wouldn’t bust / and we couldn’t, couldn’t quench our lust / There we were all together for ever and ever / and tomorrow had better beware because / when we’ve wept and slept we will be there to shake its bloody neck.’

Some more of Jeremy’s Ultra Nothing poetry written when he was at the University of New England in 1965 and 1966, aged 19 and 20.

Those of us who know Jeremy personally are all beneficiaries of his rare soul-guided generosity and nurturing nature. Some evidence of this can be found in the beautiful and thoughtful handmade gifts and drawings Jeremy has created for many people over the years, even those he barely knows, to thank them for some help they have given him or as a way to help them in their particular life’s struggles. These collages set in cotton wool of gem-like shells he collected at Henley Beach in Adelaide, South Australia in 2007 when he and Annie were there getting special acupuncture treatment for Jeremy’s chronic fatigue are examples of such gifts. Regarding his chronic fatigue, we eventually discovered an incredible Russian device called SCENAR that effectively cured Jeremy. He now uses daily for on average one hour a more advanced German designed device called ‘Physiokey’ and this is what has kept him well and able to continue his world-saving writing. So thank heavens for Physiokey!

It was the very pink pipi shells that Jeremy found occasionally on Henley beach that he thought were especially beautiful. Jeremy has written about the colours of sea shells that ‘the harmony of the colours of sea shells comes from the fact that all the different colours are from the one colour spectrum—indeed they could be regarded as all shades of the one mauve colour. It is as if Huey (God/Integrative Meaning) has one particular palette he uses for colouring sea shells. Possibly it’s the only variety of colour he could find that would stick to them in the tough environment of sea water! It starts from a deep purple that is virtually black that you see on mature mussels and grades through all shades of purple, then all shades of mauve, then all shades of pink, then all shades of yellow, then all shades of orange (even a greenish orange), then all shades of red and, of course, pure white. But all these shades are in the one family of colour type. If you put a true green or a true blue item for example in amongst them they all become unhappy and shy away from it; it just doesn’t belong in their family. Huey’s palette for colouring shells is very particular!’

Jeremy sorting through his shell collection from Henley beach on

one of his Griffith Tablecraft tables from his furniture factory.

Hanging shells and a sculpture of different items, including

a Baobab seed pod and Acacia thorns from Africa that

Jeremy’s great friend, Tim Macartney-Snape gave him.

Part of the shell and lure mural shown

below that Jeremy created in his car.

Jeremy said about this beautiful muscle shell that he found on a Sydney beach that because they usually get washed onto the beach facing down, people don’t see them, but he saw half of this one and turned it over to reveal it’s lustrous underside and then found the other half at the other end of the beach!

Going for a drive to a nearby beach where he collects these colourful shells is one of Jeremy’s distractions from the intensity of his work, so it’s just lovely that he can look at the beautiful natural shells (and all these colours are natural) every time he gets in the unnatural body of the car. Annie said about the shells, ‘even though Jeremy’s soul is more beautiful than all the shells in the whole world, these shell mosaics show all the wonder and vibrancy of the free world’ to which Jeremy replied, ‘Yeah, what’s coming is the most exciting time you could ever imagine, when this starts to catch on the biggest party you could ever dream of will begin, the weights are going to come off at last and people won’t be able to stop smiling and laughing and hugging each other, I can feel it coming, from moment to moment I can feel it, sometimes it’s so strong it almost stops me from breathing. Last night I didn’t get much sleep because I couldn’t stop listening to all our 50s and 60s music, and I could hear every word they were singing. This is Sam Cooke, “It’s been a long time coming but I know a change is going to come, Oh yes it will”.’ These words are so beautiful and precious they should be up in lights somewhere or on a T-shirt with the photo of the little joyous boy on his bike at the beginning of this document. As WTM founding member Susan Armstrong said when she read them, ‘My God Jeremy, I’m with Annie, what you wrote is what Emily would love most despite how incredible those shells are, they are just a small window into your soul and what it so deeply knows. I could dissolve into tears and fly at the same time after your words.’

Jeremy making the shell necklace present (shown below left) in September 2013.

Jeremy carved this walking stick as a gift for WTM founding member Sam Belfield in 1996. Sam is 6f 5in (197cm) tall so it was designed to cater for his very tall frame.

The chair hanging on the wall beside Jeremy’s collection of aboriginal artefacts in the picture below was a gift from Jeremy to Annie in 1983 for her 21st birthday. He found the chair, which was broken, and carved Tweeka, their pet possum, into a piece of wood which he used to repair the top of the chair. The wicker webbing in the seat was torn so Jeremy re-webbed it with thin wire which can’t tear, which was an innovative addition.

Jeremy and Annie in Sept. 1982. As mentioned above, Jeremy can’t type or text and in those days Annie typed up Jeremy’s writing on a ‘Vydec’, which was the world’s first word processor, later obsoleted by computers.

Jeremy’s mother loved trees, undertaking extensive tree planting programs wherever she went and founding, along with two other families in the district, the Althofer’s and the Harris’, the renowned Burrendong Dam Arboretum of Australian plants in Central NSW which Jeremy, when he was a young boy, was asked to design the logo for (it has now been updated but was used for some 30 years). Jeremy’s interest in designing and manufacturing a range of natural timber furniture—his acclaimed Griffith Tablecraft furniture—was a product of this shared love of trees and timber. Jeremy made the bush chair below as a gift in 1994, the design making up part of a range of very simply constructed stick furniture. In fact, Jeremy has invented a simple, practical design for almost every household item.

Jeremy, his younger brother Simon and Jeremy’s partner Annie held a memorial service for

Jeremy and Simon’s mother Jill when she passed away in 2008. Jeremy and Simon are seen here

just before the service planting a pink Western Australian Flowering Gum tree in her memory,

with a plaque describing her love of trees and the significance of her role in bringing about

Jeremy’s world-saving explanation of the human condition.

The plaque reads: ‘Jill loved trees, planting them everywhere she went, and this is such a lush and vibrant little tree that it is ongoing living energy to represent all the flowering beauty that is to come from this, the very centre of the world that, against all the falseness, Jill’s incomparable core strength protected into being.’ Jeremy, Simon, Annie and the WTM 4th Sept 2008.

Simon, Jeremy and Annie with their arms raised for the

sun-filled world full of ‘the flowering beauty that is to come’!

Jeremy’s gift to WTM founding member Susan Armstrong for her 21st birthday

and the birthday plaque complete with ‘quartz crystal’ jewel.

Jeremy’s range of stick furniture so everyone can make their own furniture!

Jeremy also designed the covers of all his books, established a style guide for the typesetting of all his publications, designed the studio set for the videos on our website, and designed all the WTM posters seen in those videos and in FREEDOM, including the one he is working on in the pictures below in 2008 titled, Humanity’s Situation: The Sunshine Highway to Freedom, The Abyss of Depression, Our Cave-like Dead Existence and The Spiralling Pit of Terminal Alienation.

See also Jeremy’s Griffith Tablecraft furniture and his remarkable search for the

Tasmanian Tiger. For insights into Jeremy’s ability to

grapple with and solve the human condition, see Freedom Essays 49 to 51.