Freedom Expanded: Book 1—The New Biology

Part 8:4B Love-Indoctrination

As stated in Part 8:2, while the integrative limitation of genes of having to always selfishly ensure their own reproduction was the normal situation, Negative Entropy did find one way to overcome this limitation, which was through nurturing—a mother’s maternal instinct to care for her offspring. Throughout this Part it will be shown that evidence, from the anthropological record as well as that provided by living non-human primates, overwhelmingly indicates that it was this nurturing path to integration that our distant ape ancestors took.

Genetic traits for nurturing are selfish (which, as stated, genetic traits normally have to be), for through the nurturing and fostering of offspring who carry her genes the mother’s genetic traits for nurturing are selfishly ensuring their reproduction into the next generation. However, while nurturing is a genetically selfish trait, from an observer’s point of view it appears to be unconditionally selfless behaviour—the mother is giving her offspring food, warmth, shelter, support and protection for apparently nothing in return. This point is most significant because it means from the infant’s perspective, its mother is treating it with real love, which, as explained in Part 8:1, is unconditional selflessness. The infant’s brain is therefore being trained or conditioned or indoctrinated with unconditional selflessness and so, with enough training in unconditional selflessness, that infant will grow into an adult who behaves unconditionally selflessly. Apply this training across all the members of that infant’s group and the result is a fully integrated society.

The ‘trick’ in this ‘love-indoctrination’ process lies in the fact that the traits for nurturing are encouraged, or selected for genetically, because the better infants are cared for, the greater are their, and the nurturing traits’, chances of survival. This process does, however, have an integrative side effect in that the more infants are nurtured, the more their brains are trained in unconditional selflessness. There are very few situations in biology where animals appear to behave unconditionally selflessly towards other members of their species—normally, they each selfishly compete for food, shelter, territory and mating opportunities. Maternalism, a mother’s nurturing of her infant, is one of the few situations where an animal appears to behave selflessly towards another animal and it was precisely this appearance of selflessness that provided the opportunity for the development of love-indoctrination or training in unconditional selflessness in our ape ancestors.

I would now like to explain in more detail how the process of ‘love-indoctrination’ overcame the inability of genes to develop love or selflessness.

In Part 8:2 it was pointed out that the most amount of selflessness that can as a rule or normally develop genetically (that is, not taking into account the love-indoctrination opportunity) is reciprocity, where one individual ‘selflessly’ helps another on the proviso that they are ‘selflessly’ helped in return, which in effect means that both parties are behaving selfishly with their own benefit in mind—so far from being selfless, reciprocity is actually entirely driven by selfish behaviour.

Normally, only traits that are selfish—that is, traits that tend to reproduce—can become established in a species. Whenever a selfless genetic mutation, a selfless trait, appears in a species it undermines its chances of reproducing, that being what selflessness means—putting others before yourself, advantaging others at your own expense. Apart from the opportunity presented by love-indoctrination, the only way selflessness could develop would be if all members of a group have the selfless gene/trait because as soon as one member doesn’t have it they will be advantaged by the selfless treatment it would receive from the others, prospering to their detriment. For example, imagine if a mother was born with a mutation that meant all her offspring were born with an inclination to behave selflessly. If she were to live isolated from others it is feasible that she could produce a small group of offspring who all behaved selflessly. So, in such circumstances it would be possible to develop a group where every member had the selfless trait, BUT the problem then would be how to maintain that delicate equation against outside influences—for any pressure from limited food, shelter or territory would inevitably result in a breakout of competition for those limited resources, thus threatening that selfless behaviour. The greater the deficiency in needed resources, the harder it would be for selflessness to be maintained. Since ideal conditions of there being ample food, shelter and territory are going to be rare, and if or when they do occur are unlikely to last, the reality is that even this scenario for establishing a selflessly behaved fully integrated new species is not going to be sustainable. The fact is, selfless behaviour cannot become established except through love-indoctrination. (Again, by ‘selfless behaviour’ I mean ‘unconditionally selfless behaviour’ because, as explained, the conditional selflessness involved in reciprocity, where others are selflessly helped on the proviso that the selfless favour is returned, is in truth selfish behaviour because it is only done on the basis of mutual benefit.)

What is significant about the nurturing, love-indoctrination opportunity to develop selflessness is that it is not based on a selfless genetic mutation that, as just described, is in reality impossible to establish in a species, but rather nurturing, which is a behaviour favoured by genetics; in fact, nurturing is a well established behaviour, at least among mammals who suckle their young. As will become clear, this nurturing of selflessness or love does depend on, firstly, the ability to develop nurturing by selecting for more maternal mothers and longer infancy periods for the training of love, and, secondly, on there being ideal conditions: ample food, territory and shelter, including an absence of competition for resources from other species. A shortage of any of these factors will cause a breakout of selfish competition for the limited resource, with those who are inclined to be selfless losing out to those who are selfish. BUT—and this is most significant—nurturing is a behaviour that does keep occurring, which means it is not eliminated by a breakout of selfish opportunism like a selfless genetic mutation would be. The traits for nurturing don’t disappear when selfish competition occurs—they are always there to be developed if a species finds itself in a position to be able to develop love-indoctrination. As will become clear, while love-indoctrination is an extremely difficult and fragile process to develop, it can be developed; setbacks can be overcome and full integration finally achieved. As we are going to see, such integration occurred in our ape ancestor, the result being our fabulous unconditionally selfless instinctive moral self or soul, the expression or ‘voice’ of which within us is our ‘conscience’.

Yes, as we will see, love-indoctrination is a fragile, difficult development because it does depend on a species being both exceptionally able to develop nurturing and fortunate enough to live in ideal conditions—but it also has the advantage of being able to survive a breakout of selfishness. Certainly, if a species can develop this nurturing love-indoctrination ‘trick’, there is still the fundamental genetic difficulty that while the nurturing of infants is strongly encouraged genetically because it ensures greater infant survival, the side effect of training infants to behave selflessly as adults is that selflessly-behaving, and even self-sacrificing, adults tend not to reproduce their genes as successfully as selfishly-behaved adults. The genes for the exceptionally maternal mothers so necessary for the development of love-indoctrination tend not to endure because their offspring tend to be the most selflessly behaved—they are too ready to put others before themselves, leaving the more aggressive, competitive and selfish individuals to take advantage of their selflessness, with males in particular seizing any mating opportunities for themselves. Such break-outs of selfish opportunism can, however, be substantially countered by ensuring all members of the group are equally well nurtured with love, equally trained in selflessness—this situation being another of the delicate balances that has to be maintained if love-indoctrination is to develop. As emphasised, any breakdown in nurturing across a group that is in the midst of developing love-indoctrination would see the whole situation revert to the old state of the ‘each-for-his-own’, opportunistic, all-out-competition-where-only-dominance-hierarchy-can-bring-some-peace, selfish-genes-rule, ‘animal condition’. So, while the love-indoctrination process has some robustness, some ability to keep occurring and therefore to survive a breakout of selfish opportunism (a tenacity the selfless mutation didn’t have) it is certainly still a delicate and difficult development—but the whole point is that, delicate as it is, love-indoctrination did provide a way for Negative Entropy or ‘God’ or the integrative development of order of matter process to integrate sexually reproducing individuals and produce a fully integrated large multicellular animal species, which, as we will see, was our australopithecine ancestors. Negative Entropy or ‘God’ did find a way to develop the Specie Individual, the integration of the sexually reproducing individual members of a species into one fully integrated, cooperatively behaved, ordered species.

To now look more closely at how love-indoctrination developed. In order to foster nurturing—this ‘trick’ for overcoming the gene-based learning system’s seeming inability to develop unconditional selflessness—a species required the capacity to allow its offspring to remain in the infancy stage long enough for the infant’s brain to become trained or indoctrinated with unconditional selflessness or love.

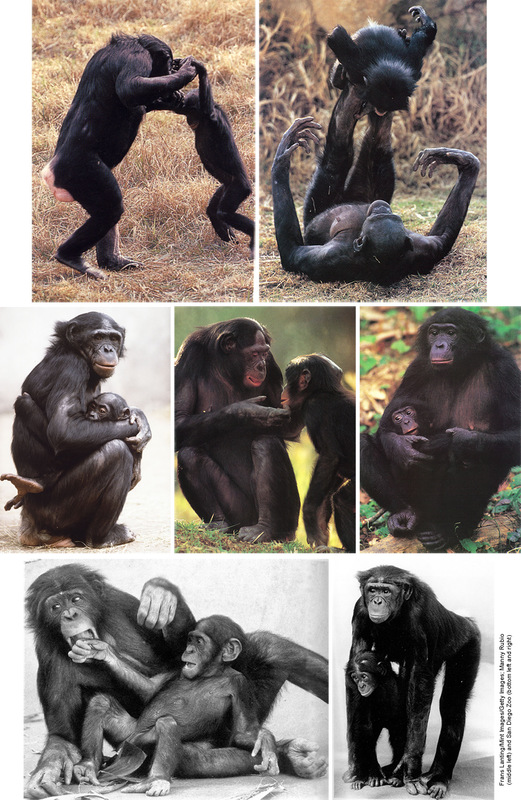

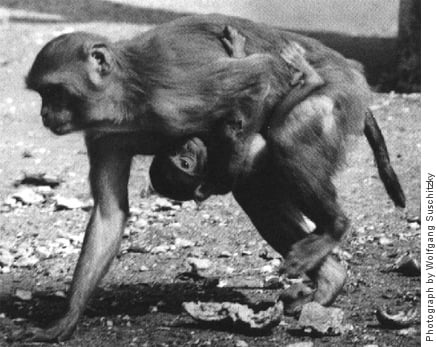

Rhesus monkey with infant. This picture illustrates the difficulty

of carrying an infant and suggests the reason for bipedalism.

In most species, infancy has to be kept as brief as possible because of the infant’s extreme vulnerability to predators. Zebra foals, for example, have to be capable of independent flight almost as soon as they are born, which gives them little opportunity to be trained in selflessness. As the above photo of a rhesus monkey trying to carry its infant illustrates, being semi-upright as a result of their tree-living, swinging-from-branch-to-branch, arboreal heritage meant primates’ arms were largely freed from walking and thus available to hold dependents. Infants similarly had the capacity to latch onto their mothers’ bodies. This freedom of the upper body meant primates were especially facilitated for prolonging their offspring’s infancy and thus developing love-indoctrination. A species that cannot carry and thus easily look after its infants, and where infants can’t easily hold onto their mothers, cannot prolong infancy and thus develop love-indoctrination.

The exceptionally maternal, matriarchal, cooperatively behaved bonobo species (Pan paniscus) provide living evidence of a species in the final stages of developing this training-in-love process. Indeed, not only are bonobos extraordinarily loving and nurturing of their infants and the most cooperative and peaceful of all non-human primates, they are also the non-human primate that is most often seen walking upright, which, along with their peaceful cooperative nature, we can now explain. The longer infancy is delayed, the more and longer infants had to be held, and thus the greater selection for arms-freed, upright walking.

Humans’ bipedalism is, therefore, a direct result of the love-indoctrination process and, as such, must have developed early on in the emergence of humans. Indeed, when I first put forward this nurturing, ‘love indoctrination’ explanation for humans’ unconditionally selfless moral soul in my 1983 submission to Nature and New Scientist magazines (which can be read at <www.humancondition.com/nature>), I pointed out at the time that, contrary to prevailing views, it meant bipedalism must have developed early in this nurturing of love process, and in fact the early appearance of bipedalism in the fossil record of our ancestors is now being found. For example, in 2009 it was reported that a ‘4.4 million-year-old skeleton of a likely human ancestor known as Ardipithecus ramidus’, discovered in Ethiopia in 1994, has features that indicate it ‘walked upright on two legs’ (‘A Long-Lost Relative’, TIME mag. 12 Oct. 2009).

While bipedalism was the key factor in developing nurturing and thus love-indoctrination, other influences also played a pivotal role, most notably the presence of ideal nursery conditions. This of course entailed uninterrupted access to food, shelter and territory, for if any element was compromised, or other difficulties and threats from predators excessive, then we can assume that there would have been a strong inclination to revert to more selfish and competitive behaviour. The successful nurturing of infants therefore required ample food, comfortable conditions and security from external threats. However, it wasn’t enough to simply look after them—in addition to these practical factors, the infants had to be loved, and so maternalism became about much more than mothers simply protecting and providing for their young: it became about actively loving them. Significantly, we speak of ‘motherly love’, not ‘motherly protection’.

So, in addition to needing to select for the ability to prolong infancy periods to allow for the training of unconditionally selfless love, and requiring ideal nursery conditions to support this process, a further factor needed to occur—the selection for more maternal mothers. But as just pointed out, the difficulty with selecting for more maternal mothers is that their genes don’t tend to endure because their offspring tend to be the most selflessly behaved, too ready to put others before themselves, leaving the more aggressive, competitive and selfish individuals to take advantage of their selflessness—but, again, such selfish opportunism could be avoided if all members of the group were equally well nurtured with love, equally trained in selflessness—as tenuous as that was in itself.

Taking into account all of these considerations, love-indoctrination was obviously an extremely difficult development even for the advantageously-built primates. It also has to be remembered that delaying maturity, as love-indoctrination does, postpones the addition of new generations that are so vital for the maintenance of a species whose reproduction is limited mostly to single offspring births. New generations ensure variety. Indeed, the numerous and not incidental challenges involved would explain why almost all primate species have not been able to complete the development of love-indoctrination to the point of becoming fully integrated.

For instance, bonobos, or pygmy chimpanzees as they were once called, have lived in the food-rich, shelter-affording ideal nursery conditions of the rainforests south of the Congo River and are by far the most cooperative/harmonious/cohesive/social/selflessly behaved/integrated of the non-human primates. The comfort of the bonobos’ environment and their cooperativeness compared to that of their chimpanzee cousins (or Pan troglodytes) who live north and east of the Congo River, is apparent in this quote: ‘we may say that the pygmy chimpanzees historically have existed in a stable environment rich in sources of food. Pygmy chimpanzees appear conservative in their food habits and unlike common chimpanzees have developed a more cohesive social structure and elaborate inventory of sociosexual behavior. In contrast, common chimpanzees have gone further in developing their resource-exploiting techniques and strategy, and have the ability to survive in more varied environments. These differences suggest that the environments occupied by the two species since their separation by the Zaire [Congo] River has differed for some time. The vegetation to the south of the Zaire River, where Pan paniscus is found, has been less influenced by changes in climate and geography than the range of the common chimpanzee to the north. Prior to the Bantu (Mongo) agriculturists’ invasion into the central Zaire basin, the pygmy chimpanzees may have led a carefree life in a comparatively stable environment’ (The Pygmy Chimpanzee, ed. Randall L. Susman, ch.10 by Takayoshi Kano & Mbangi Mulavwa, 1984, p.271 of 435). It is an indication of just how difficult it is to develop love-indoctrination that even the bonobos, living as they do in their ideal conditions—and who ‘have developed a more cohesive social structure’ than their chimpanzee relatives—have found it necessary to employ sex as an appeasement device to help subside residual tension and aggression between individuals; this is the ‘elaborate inventory of sociosexual behavior’ referred to in this quote.

Of the key resources animals need of food, shelter, territory and a mate, while a situation can be reached of there being sufficient food, shelter and territory, from a genetic point of view there can usually never be enough mates, simply because the more successfully an individual can breed, the more their genes can carry on and multiply. Since females are obviously limited in how often they can reproduce due to pregnancy and, in the case of mammals, lactation, it is the males who have the opportunity to breed continuously, and so it is the competition for mating opportunities by the males that is the most difficult form of genetic selfishness to overcome. Making mating opportunities available to everyone all the time, as bonobos do, would be one way of rendering competition for mating opportunities obsolete—after all, if everyone is regularly mating with everyone else then there really isn’t any competition. Further, what aggression and tension does still occur would be greatly appeased by making readily available the feelings of pleasure, excitement and fulfilment that have historically become biologically associated with mating to ensure and encourage its occurrence. Shortly, it will be explained that monogamy is an even more effective way of containing sexual opportunism, but for that to develop, and, as will be explained, it would have developed in our australopithecine forebears, selfishness had to already have been completely overcome, which, at the bonobo’s stage of developing integration, is not the case. Even making mating opportunities available to everyone, and concealing ovulation, which is also practiced by bonobos to reduce the aggression from males competing for mating opportunities, could not be developed until the typical fierce competition for mating opportunities that exists amongst mammal males had largely been brought under control by love-indoctrination. This is because whilst ever competition to mate is intense, if a female makes mating available to every male, and/or doesn’t advertise she is ready for fertilisation, she can’t ensure she mates with the strongest, most virile male and her offspring won’t be successful competitors. Making sex continually available and concealing ovulation could assist love-indoctrination but not initiate the development of love/unconditional selflessness.

I will continue this analysis of bonobo behaviour in further detail in Part 8:4F, but it should already be clear that although the process is not yet complete, this species has been able to develop a great deal of love-indoctrination, which means a great deal of training in unconditional selflessness. Like all primates, bonobos are exceptionally facilitated by their arms-free arboreal heritage to prolong the infancy period needed to develop love-indoctrination. They have also especially benefited from the ideal nursery conditions of their home in the food-rich Congo River basin. The result is that bonobos have been able to develop the nurturing that love-indoctrinated training in selflessness depends on to such a high degree that they have even been able to bring to an end that most difficult of all forms of selfish competitiveness, male competition for mating opportunities (although they still have to employ sex as a way of appeasing residual tension and aggression). In fact, bonobos have been so successful at reining in male competition for mating opportunities that within bonobo society there has been what could be described as a gender-role reversal, with bonobo females forming alliances and dominating social groups, both of which are distinctly male activities in chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan and other non-human primate societies. As will be explained more fully in Parts 8:4F and 8:4G, when further comparison is made between bonobos and chimpanzees, bonobo society is matriarchal, female-dominated, controlled and led. Further, in bonobo society, the entire focus of the social group does seem to be on the maternal or female role of nurturing infants. The following photographs of bonobos with infants reveal something of just how exceptionally nurturing bonobo females are—and even males, because the bottom left photo is of a male lovingly playing with an infant. Bonobos clearly have the environmental comfort and the freedom from fighting and tension in their world needed to develop the ability to love their infants.

This gender-role reversal in bonobo society is a stupendous achievement, a very great breakthrough in the development of integration. When watching wildlife documentaries or observing animals in nature, what is so very apparent is how the females of most animal species taunt the males—letting them fight with each other furiously, having them chase them endlessly, encouraging (in the case of birds) the growth of ever more exotic plumage, etc, etc—so that they can establish which is the strongest, most virile male to mate with, obviously to ensure their offspring will also inherit the strongest, most virile genetic make-up. So, to bring about a change where instead of the strongest and most aggressive males being successful in winning mating opportunities, the most gentle, least aggressive are the most successful and favoured is a truly extraordinary turnaround, but that is what the bonobos (and our own ape ancestors) achieved! As extremely difficult as it is to develop, such is the awesome power of the love-indoctrination tool for developing integration! Importantly, to achieve this amazing gender-role reversal, this incredible change from patriarchy to matriarchy, love-indoctrination was assisted by an emerging conscious mind. Just how love-indoctrination enabled consciousness to emerge and come to the assistance of the love-indoctrination process will be explained next in Parts 8:4C and 8:4D, but one of the other amazing attributes of bonobos is that they are the most conscious, the most intelligent of all animals next to humans.

In the context of our own human origins, it follows from what has been said that for our ape ancestors to have become totally cooperative and integrated—to have developed an unconditionally selfless, altruistic, moral instinctive self or ‘soul’, as I am asserting occurred—they must have been blessed with all the conditions necessary to complete the love-indoctrination process; in particular, they must have lived in ideal nursery conditions in their home somewhere in Africa. (We know from fossil evidence that our original ancestors emerged in Africa—as we intuitively recognised, Africa was, as we say, ‘the cradle of mankind’—but we don’t as yet know the exact location of this original ‘nursery’.)

It has to be emphasised again that while the bonobos have almost completed the love-indoctrination process and become a fully integrated Specie Individual like our ape ancestors did, the fact that they still have to employ sex as an appeasement device to quell remaining tension and aggression indicates they haven’t quite succeeded. Similarly, while chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans and even baboons and some other monkeys have also been able to develop love-indoctrination to the point of achieving a high degree of integration, they too have failed to complete the love-indoctrination development of integration—indeed, as will be described more fully shortly, they have yet to overcome the problem of male mating opportunism because their societies are still male-led or patriarchal. The fact that all these primates are still unable to complete the love-indoctrination process demonstrates that it is an extremely difficult development. The reality is that developing love-indoctrination to the point where the indoctrinated love or unconditional selflessness or altruism or morality becomes instinctive (a process that will be explained shortly) was akin to trying to swim upstream to an island—any difficulty or breakdown in the nurturing process and you are invariably ‘swept back downstream’ once more to the old competitive, selfish, each-for-his-own, opportunistic situation. Powerful illustrations of how any disruption to the love-indoctrination process quickly can lead to a regression back to the more competitive, opportunistic, pre-love-indoctrination, animal-condition-afflicted situation will be provided shortly in Part 8:4G.

Thus, while the development of unconditional selflessness through the love-indoctrination process of a mother’s nurturing care of her infant was possible, it was a very difficult, and also a very slow, process. What the situation needed was a mechanism to assist, speed up and help maintain love-indoctrination’s development of integration—assistance that came from the emergence of a conscious mind. What began to occur was the conscious self-selection of integrativeness, especially the female sexual or mate selection of less competitive and aggressive, more integrative males with which to mate. (It might be mentioned that in his 1871 book The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, Charles Darwin suggested the role mate selection could have played in our human development, although he didn’t understand its significance in the context of the love-indoctrination process.)

Later, in Part 8:7B, ‘Why, how and when did consciousness emerge in humans?’, it will be fully explained how the nurturing, love-indoctrination process liberated consciousness in our ape ancestors and that it was the emerging conscious intellect in our forebears that began to support the development of selflessness, for when our ape ancestors became conscious they were able to recognise the importance of selflessness and, having realised that, begin to actively select for it.

However, in the interim and for the purposes of explaining this conscious self-selection of selfless cooperativeness process, a brief summary of the full explanation that appears in Part 8:7B will be provided next, in Part 8:4C. But before doing so, I should quickly point out that with love-indoctrination and mate selection of cooperative integrativeness recurring over many generations, unconditional selflessness or love would have eventually become instinctive or innate. This is because once unconditionally selfless individuals were continually appearing, the genes ‘followed’ the whole process, reinforcing that selflessness. Similarly, when the conscious mind fully emerged within humans and went its own way—embarked on its course for knowledge—genetic adaptation followed, reinforcing that development. Generations of humans whose genetic make-up in some way helped them cope with the human condition were selected naturally—making, amongst other adjustments, humans’ alienated state somewhat instinctive today. We have been ‘bred’ to survive the pressures of the human condition; to block out or deny the issue of the human condition has been our main way of coping with the dilemma it represented. Genes inevitably follow and reinforce any development process—in this they are not selective. The difficulty lay in getting the development of unconditional selflessness to occur, for once it was regularly occurring it would naturally become instinctive over time. Thus, with unconditional selflessness or love occurring over many generations and becoming instinctive or innate, our instinctive moral self or soul, the ‘voice’ of which is our ‘conscience’, became established in our ape ancestors. A powerful illustration of this moral instinct in us that continues to guide us to behave in this all-loving way was given in a Sports Illustrated magazine article that reported how Joe Delaney, a professional footballer, acknowledged that ‘I can’t swim good, but I’ve got to save those kids’, just moments before plunging into a Louisiana pond and drowning in an attempt to rescue three boys (‘Sometimes The Good Die Young’, 7 Nov. 1983). This is but one example of our moral, altruistic nature in action, but no doubt we have all heard, seen, or read of similar situations.

In terms of developing love-indoctrination, obviously the more instinctive unconditional selflessness or love became, the more any regression to selfish behaviour was able to be resisted. Instincts have their own power, their own ability to ensure that what they expect happens, so as love became instinctive so love, unconditional selflessness, became a stronger force.

An important point that should also be made before presenting the summary of how consciousness emerged is how difficult it has been for denial-complying, human-condition-avoiding, mechanistic science to even consider, let alone accept, the love-indoctrination explanation for human origins; in fact, for what gave us our unique, unconditionally selfless moral instinctive self or soul. It turns out that I’m not the first person to realise and put forward the love-indoctrination explanation for our extraordinary unconditionally selfless moral sense. As will be described in Part 8:5B, when the American philosopher John Fiske first presented the idea only 15 years after Charles Darwin published his idea of natural selection in his 1859 book The Origin of Species, it prompted some very eminent scientists of that era to describe Fiske’s hypothesis of ‘the Struggle for the Life of Others’ or ‘altruistic Love’ (which was said to be ‘the real law of evolution’, and as having ‘developed in the course of evolution from the necessities of maternity’) as a ‘far more important’ ‘principle’ than Darwin’s selfish, ‘natural selection by means of the struggle for survival’; in fact, as ‘one of the most beautiful contributions ever made to the Evolution of Man’! However, in Part 8:5B I also record that despite this recognition of the immense importance of Fiske’s nurturing hypothesis for our altruistic moral nature, the idea also ‘attracted a good deal of opprobrium [abuse]’ at the time and was eventually totally ignored and left to die! Again, as pointed out in Parts 4:4D and 4:4F when the six great unconfrontable truths were described, the two truths that are being admitted in this whole nurturing, love-indoctrination explanation for our moral nature—that humans have selfless, loving instincts and that nurturing has been, and still is, so important in human development—have been unbearable to face and acknowledge. The problem is they beg the question, ‘Why aren’t we humans now loving and selflessly behaved, and why aren’t we capable of adequately nurturing our infants?’ The fact is, it is only now that we can explain our upset, corrupted, embattled, little-time-for-nurturing, human-condition-afflicted lives that we can afford to admit these truths. The truth that can now at last be admitted is that nurturing was the main influence or prime mover in human development—not tool use or bipedalism or language development or mastery of fire or any one of the other evasive explanations that denial-complying biologists have been putting forward in the mountain of books that have been published on human origins. The nurturing explanation for human origins is actually a reasonably obvious truth if you are thinking in a denial-free truthful way because in time it should occur to you that in the maternal situation there already exists an apparently unconditionally selfless relationship and thus the potential for true integration to develop. But as with so many historically unbearable truths, it is only now that the human condition has been explained that it finally becomes psychologically safe to admit all these unbearable truths, including the importance of nurturing and the existence of our moral soul.