‘FREEDOM’—Chapter 2 The Threat of Terminal Alienation from Science’s Denial

Chapter 2:3 Our near total resistance to analysis of the human condition post-Resignation

It is a measure of just how unbearable the issue of the human condition has been that while Resignation has been the most important psychological event in human life the process is never spoken of and has virtually gone unacknowledged in the public realm, with only a rare few of our most accomplished writers even managing to write about the suicidally depressing experience of engaging the subject of the human condition itself. To this end, many ‘philosophers and psychologists’ consider that the great Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard’s ‘analysis on the nature of despair is one of the best accounts on the subject’ (Wikipedia; see <www.wtmsources.com/137>)—with the ‘nature of despair’ being as close as the reviewer could go in referring to the worse-than-death, suicidal depression that the human condition has caused humans, but which Kierkegaard managed to give such an honest account of in his aptly titled 1849 book, The Sickness Unto Death: ‘the torment of despair is precisely the inability to die [and end the torture of our unexplained human condition]…that despair is the sickness unto death, this tormenting contradiction [of our ‘good and evil’, human condition-afflicted lives], this sickness in the self; eternally to die, to die and yet not to die’ (tr. A. Hannay, 1989, p.48 of 179). Kierkegaard went on to include these unnervingly truthful words about how, even when the blocks were in place in our minds against recognising the existence of the issue of the human condition, the terrifying ‘anxiety’ it caused us still occasionally surfaced: ‘there is not a single [adult] human being who does not despair at least a little, in whose innermost being there doesn’t dwell an uneasiness, an unquiet, a discordance, an anxiety in the face of an unknown something, or a something he doesn’t even dare strike up acquaintance with…he goes about with a sickness, goes about weighed down with a sickness of the spirit, which only now and then reveals its presence within, in glimpses, and with what is for him an inexplicable anxiety’ (p.52).

Another great philosopher, the Russian Nikolai Berdyaev, gave this extraordinarily forthright description of how trying to address and solve the sickeningly depressing issue of the human condition and, by so doing, make sense of human behaviour, has been a nightmare: ‘Knowledge requires great daring. It means victory over ancient, primeval terror. Fear makes the search for truth and the knowledge of it impossible…it must also be said of knowledge that it is bitter, and there is no escaping that bitterness…Particularly bitter is moral knowledge, the knowledge of good and evil. But the bitterness is due to the fallen state of the world, and in no way undermines the value of knowledge…it must be said that the very distinction between good and evil is a bitter distinction, the bitterest thing in the world…There is a deadly pain in the very distinction of good and evil, of the valuable and the worthless’ (The Destiny of Man, 1931; tr. N. Duddington, 1960, pp.14-15 of 310). Yes, trying to think about our corrupted, ‘fallen’, seemingly ‘evil’ and ‘worthless’ state has been an ‘ancient, primeval terror’, a ‘deadly pain’, ‘the bitterest thing in the world’ for virtually all humans. As one of the key figures of the Enlightenment, the philosopher Immanuel Kant, said: we have to ‘Dare to know!’ (What is Enlightenment?, 1784).

So Carl Jung certainly exhibited ‘great daring’ in his thinking when he wrote the following words about the terrifying nature of the human condition: ‘When it [our shadow] appears…it is quite within the bounds of possibility for a man to recognize the relative evil of his nature, but it is a rare and shattering experience for him to gaze into the face of absolute evil’ (Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self, 1959; tr. R. Hull, The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol. 9/2, p.10). The ‘face of absolute evil’ is the ‘shattering’ possibility—if we allowed our minds to think about it—that we humans might indeed be a terrible mistake. And so to avoid that implication, humans have had to avoid almost all deep, penetrating, truthful thinking because almost any thinking at a deeper level brought us into contact with the unbearable issue of our seemingly horribly flawed condition: ‘There’s a tree with lovely autumn leaves; isn’t it amazing how beautiful nature can be, I wonder why some things are beautiful while others are not—I wonder why I’m not beautiful inside, in fact, so full of all manner of angst, selfish self-obsession, indifference and anger…aaahhhhh!!!!’ The very great English poet William Wordsworth was making this point when he wrote, ‘To me the meanest flower that blows can give thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears’ (Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood, 1807), for it is true that even the plainest flower can remind us of the unbearably depressing issue of our seemingly horrifically imperfect, ‘fallen’, apparently ‘worthless’ condition. Yes, as the comedian Rod Quantock once said, ‘Thinking can get you into terrible downwards spirals of doubt’ (‘Sayings of the Week’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 Jul. 1986). The Nobel Laureate Albert Camus wasn’t overstating the issue either when he wrote that ‘Beginning to think is beginning to be undermined’ (The Myth of Sisyphus, 1942); nor was another Nobel Prize winner in Literature, Bertrand Russell, when he said, ‘Many people would sooner die than think’ (Antony Flew, Thinking About Thinking, 1975, p.5 of 127). And nor was the equally acclaimed poet T.S. Eliot when he wrote that ‘human kind cannot bear very much reality’ (Burnt Norton, 1936). ‘The sleep of reason’, letting down our mental guard, does indeed ‘bring forth monsters’. I might mention that the rock band U2’s 1992 song Staring At The Sun contains these revealing lyrics about how afraid we have been of encountering the human condition: ‘It’s been a long hot summer, let’s get under cover, don’t try too hard to think, don’t think at all. I’m not the only one staring at the sun, afraid of what you’d find if you take a look inside. Not just deaf and dumb, I’m staring at the sun, not the only one who’s happy to go blind.’

Already we can see the truth of the initial point made in this chapter—that to understand human behaviour requires bottoming out on the fact that almost all of our behaviour is a product of, even driven by, our fear of the human condition, for we can appreciate here how our fear of the human condition has limited, indeed relegated, us to an extremely superficial existence. As this book progresses, it will become increasingly clear that making sense of human behaviour and finding the answers to all the mysteries about human life depends on recognising humans’ immense fear of the human condition. Moreover, recognising this underlying fear will enable you to see through our behaviour, see what is behind it, what is causing it—to such an extent, in fact, that our behaviour becomes transparent. You can get a feeling for this concept of transparency in the comment by Professor Karen Riley included earlier (see par. 94).

The fact is, the human race has lived a haunted existence, dogged by the dark shadow of its imperfect human condition, forever trying to escape it—the result of which is that we have become immensely superficial and artificial; ‘phony’ and ‘fake’, as the resigning adolescents so truthfully described it, and living on the absolute meniscus of life in terms of what we are prepared to look at, feel and consider. We are a profoundly estranged or alienated species, completely blocked-off from the amazing and wonderful real world, and from the truth of our self-corruption that thinking about that beautiful, inspired, natural, soulful world unbearably connects us to—as the absolutely ‘fear’-lessly honest Scottish psychiatrist R.D. Laing has written: ‘Our alienation goes to the roots. The realization of this is the essential springboard for any serious reflection on any aspect of present inter-human life…We are born into a world where alienation awaits us. We are potentially men, but are in an alienated state [p.12 of 156] …the ordinary person is a shrivelled, desiccated fragment of what a person can be. As adults, we have forgotten most of our childhood, not only its contents but its flavour; as men of the world, we hardly know of the existence of the inner world [p.22] …The condition of alienation, of being asleep, of being unconscious, of being out of one’s mind, is the condition of the normal man [p.24] …between us and It [our true selves or soul] there is a veil which is more like fifty feet of solid concrete. Deus absconditus [God has absconded]. Or [more precisely] we have absconded [from God/the integrative ideals] [p.118] …The outer divorced from any illumination from the inner is in a state of darkness. We are in an age of darkness. The state of outer darkness is a state of sin—i.e. alienation or estrangement from the inner light [p.116] …We are all murderers and prostitutes…We are bemused and crazed creatures, strangers to our true selves, to one another’ [pp.11-12] (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, 1967). ‘We are dead, but think we are alive. We are asleep, but think we are awake. We are dreaming, but take our dreams to be reality. We are the halt, lame, blind, deaf, the sick. But we are doubly unconscious. We are so ill that we no longer feel ill, as in many terminal illnesses. We are mad, but have no insight [into the fact of our madness]’ (Self and Others, 1961, p.38 of 192). ‘We are so out of touch with this realm [where the issue of the human condition lies] that many people can now argue seriously that it does not exist’ (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, p.105).

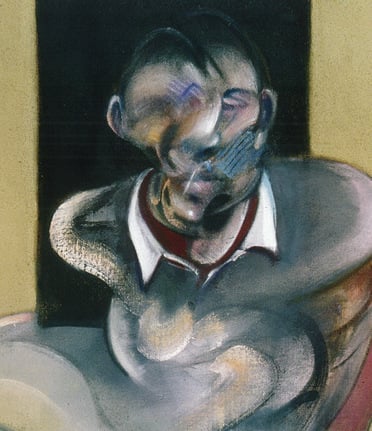

Laing’s honesty is astonishing. One other rare example from the twentieth century of someone who managed to depict and penetrate our ‘fifty feet of solid concrete’ wall of denial of the truth of our tortured, ‘good-and-evil’-stricken human condition was the Irish artist Francis Bacon. While people in their resigned state of denial of what the human condition actually is typically find his work ‘enigmatic’ and ‘obscene’ (The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 Apr. 1992), there is really no mistaking the agony of the human condition in Bacon’s death-mask-like, twisted, smudged, distorted, trodden-on—alienated—faces, and tortured, contorted, stomach-knotted, arms-pinned, psychologically strangled and imprisoned bodies; consider, for instance, his Study for self-portrait below. It is some recognition of the incredible integrity/honesty of Bacon’s work that in 2013 one of his triptychs sold for $US142.4 million, becoming (at the time) ‘the most expensive work of art ever sold at auction, breaking the previous record, set in May 2012, when a version of Edvard Munch’s The Scream [another exceptionally honest, human-condition-revealing painting] sold for $119.9 million’ (TIME, 25 Nov. 2013). (It may seem incongruous that people living in denial of the human condition should pay such exorbitant sums for such stark depictions of our psychologically upset state, but living in an almost completely ‘phony’, ‘fake’, ‘alienat[ed]…to the roots’ and truthless world, as this book reveals we have been, has meant that the honesty about our true state depicted by Bacon and Munch could be immensely valued for its cathartic, purging, purifying, relieving powers. This book, however, provides the ultimate form of this therapy, because in explaining the human condition it at last allows us to be completely honest without that honesty bringing with it any condemnation of our horrifically upset condition.)

Indeed, Laing’s words and Bacon’s images are so cathartically honest that if they don’t reconnect us with the human condition then nothing will!! But again, despite the contributions made by these great thinkers and artists, and the horror of the world around us, that reconnection is not easily achieved because what Laing wrote is true—resigned humans have learnt to live in such complete denial of the issue of the human condition that many people do now ‘seriously’ believe the issue ‘does not exist’, at least not in its true form as a profoundly disturbed and insecure, psychological affliction.

A further illustration of just how impenetrable the issue of the human condition has been is Plato’s aforementioned allegory of the cave (see par. 83) in which humans have been incarcerated, unable to face the glare of the sunlit ‘real’ world because it would make ‘visible’ the unbearably depressing issue of ‘the imperfections of human life’. Plato said that while ‘the sun…makes the things we see visible’, such that without it we can only ‘see dimly and appear to be almost blind’, having to hide in the ‘cave’ of ‘illusion’ and endure ‘almost blind’ alienation was infinitely preferable to facing the ‘painful’ issue of ‘our [seemingly imperfect] human condition’. Clearly, what enabled Plato to be such an effective and penetrating thinker was that he was able to ‘realiz[e]’ that ‘Our alienation goes to the roots’, which, as Laing wrote, is ‘the essential springboard for any serious reflection on any aspect of present inter-human life’. Plato was one of the rare few individuals in history who have been sound and secure enough in self to not have had to resign to living a life of denial of the human condition, because only by being unresigned could he have fully confronted, talked freely about and effortlessly described the human condition the way he did; you can’t think truthfully if you are living in a cave of denial.

I should mention that while there have been innumerable interpretations of Plato’s cave allegory, none that I am aware of has presented the interpretation that was given in par. 83, which was that Plato was describing humans as living in such immense fear of the human condition that they were having to hide from it in the equivalent of a deep, dark cave. However, if this interpretation is true and adult humans are living in terrifying fear of the human condition (and what has been described about Resignation evidences they are), then it makes complete sense that they wouldn’t want to acknowledge that interpretation, they wouldn’t want to admit that Plato was right about them wanting to hide from the human condition, and so they would have sought a different, less confronting interpretation. Admitting to having to hide from the human condition means acknowledging and having to confront the issue of the human condition, which humans haven’t wanted to do. And in addition to not wanting to be reconnected to the issue of the human condition and the terrible depression they experienced at Resignation, adults haven’t wanted to admit that they did resign to a life of lying—to living a completely superficial, ‘phony’, ‘fake’, ‘alienat[ed]…to the roots’, ‘asleep’, ‘unconscious’, ‘out of one’s mind’ existence. Such honesty would undermine their ability to operate; it would be self-negating: ‘I’m lying, so neither you nor I can trust me.’ No wonder humans have been so sensitive about being called liars. In the absence of understanding, denial and delusion have been the only means we have had to cope with the extreme imperfection of our lives. It is only now that we can properly explain the human condition and, by so doing, fully defend and understand our upset, corrupted, alienated state that we can afford to abandon that delusion and denial and be honest about Resignation and its consequences. Indeed, the only outright admissions of Resignation and its effects that I have found have come from exceptionally honest, unresigned, denial-free-thinking individuals we have termed ‘prophets’, namely Plato with his cave allegory, and, as will be described in par. 750, Moses with his Noah’s Ark metaphor.

We can therefore appreciate why every effort has been made to avoid the, in truth, obvious ‘we-are-hiding-from-the-human-condition’ interpretation of Plato’s cave allegory that was given in par. 83. And it is a very obvious interpretation, because, in Sir Desmond Lee’s translation of Plato’s own words, Plato wrote, ‘I want you to go on to picture the enlightenment or ignorance of our human conditions’, where the ‘fire’ that blocks the cave’s exit ‘corresponds…to the power of the sun’, which the ‘cave’ ‘prisoners’ have to hide from because its searing, ‘painful’ light would make ‘visible’ the unbearably depressing issue of ‘the imperfections of human life’—those imperfections being ‘our human condition’!

Some might question whether Lee took liberties in translating Plato’s original Greek words as meaning ‘our human condition’. The first point I would make is that Lee’s translation is held in very high regard; it is, for instance, the translation the publishing house Penguin chose for its very popular paperback edition of The Republic. And the second point I would make is that the most literal interpretation of Plato’s original Greek text, by the philosopher Allan Bloom, carries the same meaning. In his preface to his 1968 translation of The Republic, Bloom (the author of the renowned and exceptionally honest book, The Closing of the American Mind) explains why he went to such pains to be literal: ‘Such a translation is intended to be useful to the serious student, the one who wishes and is able to arrive at his own understanding of the work…The only way to provide the reader with this independence is by a slavish…literalness—insofar as possible always using the same English equivalent for the same Greek word’ (The Republic of Plato, tr. Allan Bloom, 1968, Preface, p.xi of 512). So what is Bloom’s ‘slavish[ly]’ ‘literal’ translation of the passage Lee translated as ‘picture the enlightenment or ignorance of our human conditions’?—it is ‘make an image of our nature in its education and want of education, likening it to a condition of the following kind’ (ibid. 514a). ‘Our nature’ or ‘condition’ is ‘our human condition’! I might include more of Bloom’s rendition of the passage Lee translated, on how the ‘fire’ that blocks the cave’s exit ‘corresponds…to the power of the sun’, which the cave prisoners have to hide from because its searing, ‘painful’ light would make ‘visible’ the unbearably depressing issue of ‘the imperfections of human life’, those imperfections being ‘our human condition’. Bloom’s translation of these key words and phrases is that we should ‘liken’ the ‘fire’ that blocks the cave’s exit ‘to the sun’s power’ (ibid. 517b), which the cave prisoners have to hide from because its searing, ‘distress[ing]’ (ibid. 516e) light would make ‘visible’ the unbearably depressing issue of ‘human evils’ (ibid. 517c-d), that propensity for evil being ‘our nature’. So Lee’s translation of those other key words is equally accurate.

So, despite the human condition being the all-important issue that had to be solved if we were to understand and ameliorate human behaviour, it has been, for all but a very rare few individuals like Plato and Moses, the one issue humans couldn’t face. It has been the great unacknowledged ‘elephant in the living room’ of our lives, THE absolutely critical and yet completely unconfrontable and virtually unmentionable subject in life.

With this in mind, we can now finally understand the resigned mind’s inability to make sense of human behaviour, and the problem posed by the ‘deaf effect’ when reading about the human condition, and why humans resigned to a life in denial of the human condition. And with this appreciation, it is not difficult to see the connection between our species’ denial of our condition and the following account of one woman’s reaction to being told she had cancer; her ‘block out’ or denial of her condition is palpable: ‘She said, “I thought I was cool, calm and collected but I must have been in a state of shock because the words just seemed to flood over me and I remembered almost nothing from what the doctor said in the initial consultation”’ (The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 Aug. 1995). And, since discussion of the human condition involves re-connecting with Resignation, an experience worse than death (a ‘horrible’ ‘shattering’ ‘deadly pain’ of such depressing ‘despair’, ‘doubts and night terrors’ that it was like a ‘sickness unto death’ where you ‘just keep falling and falling’, ‘eternally to die, to die and yet not to die’, as Hughes, Salinger, Kierkegaard, Berdyaev and Jung variously described it), it should be clear to the reader that even though you will think you are ‘cool, calm and collected’ and able to absorb what is being explained here, your mind will actually be in ‘shock’, so the words will ‘flood over’ you and you will ‘initial[ly]’ be, as Plato said, unable to take in or hear much of what is being said. Once you are resigned to living in denial of the issue of the human condition, as virtually every adult is, then you are living in denial of the issue of the human condition—so your mind will, at least ‘initial[ly]’, resist absorbing discussion of it. So while you may think you will be able to follow and take in discussion about what the human condition is, like you would expect when reading or learning about any new subject, this ‘deaf effect’ that ‘initial[ly]’ occurs when reading about the human condition is, in fact, very real.

The problem is that once humans resign and become mentally blocked out or alienated from any truth that brings the issue of the human condition into focus (which, as will be revealed in this book, is most truth), we aren’t then aware that we are blocking out anything; we aren’t then aware, as Laing said, that ‘there is a veil which is more like fifty feet of solid concrete’ between us and ‘our true selves’ or soul that is preventing our mind from accessing what is being said. As pointed out earlier, this inability to know we are blocking something out occurs because obviously we can’t block something out of our mind and know we have blocked it out because if we knew we had blocked it out we wouldn’t have blocked it out. The fact is, we aren’t aware that we are alienated!

So the ‘deaf effect’ is very real, and so, therefore, is the need to watch the introductory videos and have the willingness to patiently re-read the text and engage in interactive discussions about these understandings.