Part 1.4 How we humans acquired our cooperative, selfless and loving moral instincts

So the first of the two instinct and intellect features of our lives that needs to be explained for the human condition to be fully understood and ended is how we humans acquired our cooperative, selfless and loving moral instincts. (The second—how we became fully conscious—will be explained in the next Part.)

A fundamental truth in biology is that genes normally can’t select for unconditionally selfless, fully cooperative instinctive traits, simply because such traits tend to be self-eliminating and so normally can’t become established in a species—‘By all means, you can be selfless and sacrifice your genes for me but I’m not about to be selfless and sacrifice my genes for you’ has been the reality of the process of natural selection. Yes, as the biologist Jerry Coyne pointed out (see paragraph 21), the idea that selfless traits can become established in a group is false biology because of ‘the tendency of each group to quickly lose its altruism through natural selection favoring cheaters [selfish, opportunistic individuals]’. So the question is: how could such a selfish process as natural selection have created loving selfless instincts in us?

As I describe in Part 3 of THE Interview, and more fully in chapter 5 of FREEDOM (and also summarise in Freedom Essay 21), we acquired our moral instincts through nurturing. To appreciate what is so significant about a mother’s nurturing of her offspring, it first needs to be explained that a mother’s maternal instinct to care for her offspring is selfish because she is ensuring the reproduction of her genes by ensuring the survival of offspring who carry her genes. So maternalism is a selfish trait, which, as I’ve said, genetic traits normally have to be for them to reproduce and carry on into the next generation. HOWEVER, and this is all-important, from the infant’s perspective maternalism does have the appearance of being selfless. From the infant’s perspective, it is being treated unconditionally selflessly—the mother is giving her offspring food, warmth, shelter, support and protection for apparently nothing in return. So it follows that if the infant can remain in infancy for an extended period and be treated with a lot of seemingly altruistic love, it will be indoctrinated with that selfless love and grow up to behave accordingly. So selfish maternalism can train an infant in altruistic selflessness.

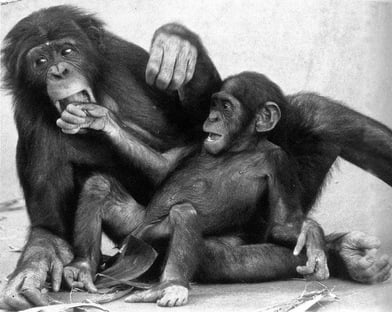

And primates, being semi-upright from living in trees (arboreal), swinging from branch to branch, and thus having their arms free to hold a dependent infant, are especially facilitated to support and prolong the mother-infant relationship, and so develop this nurtured, loving, cooperative behaviour. And in fact, bonobos, the ape species who live south of the Congo River in Africa, are extraordinarily matriarchal, or female role focused, and exceptionally nurturing of their offspring, and remarkably cooperative, selfless and loving—as these pictures of bonobos and quotes about their behaviour evidence.

Bonobo mothers holding their infants

Bonobos nurturing their infants

Bonobo zoo keeper Barbara Bell wrote that ‘Adult bonobos demonstrate tremendous compassion for each other…For example, Kitty, the eldest female, is completely blind and hard of hearing. Sometimes she gets lost and confused. They’ll just pick her up and take her to where she needs to go…They’re extremely intelligent…They understand a couple of hundred words…It’s like being with 9 two and a half year olds all day…They also love to tease me a lot…Like during training, if I were to ask for their left foot, they’ll give me their right, and laugh and laugh and laugh’ (‘The Bonobo: “Newest” apes are teaching us about ourselves’, Chicago Tribune, 11 Jun. 1998).

Researchers have also reported that ‘bonobos historically have existed in a stable environment rich in sources of food…and unlike chimpanzees have developed a more cohesive social structure’ (Takayoshi Kano & Mbangi Mulavwa, ‘Feeding ecology of the pygmy chimpanzees (Pan paniscus)’; The Pygmy Chimpanzee, ed. Randall Susman, 1984, p.271 of 435). For example, ‘up to 100 bonobos at a time from several groups spend their night together. That would not be possible with chimpanzees because there would be brutal fighting between rival groups’ (Paul Raffaele, ‘Bonobos: The apes who make love, not war’, Last Tribes on Earth.com, 2003; see www.wtmsources.com/143).

Primatologist Sue Savage-Rumbaugh said, ‘Bonobo life is centered around the offspring. Unlike what happens among chimpanzees, all members of the bonobo social group help with infant care and share food with infants. If you are a bonobo infant, you can do no wrong…Bonobo females and their infants form the core of the group’ (Sue Savage-Rumbaugh & Roger Lewin, Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind, 1994, p.108 of 299).

A filmmaker of the French documentary Bonobos observed that ‘They’re surely the most fascinating animals on the planet. They’re the closest animals to man [in that they share almost 99 percent of our genetic make-up]. They’re the only animals capable of creating the same “gaze” as a human…Once I got hit on the head with a branch that had a bonobo on it. I sat down and the bonobo noticed I was in a difficult situation and came and took me by the hand and moved my hair back, like they do. So they live on compassion, and that’s really interesting to experience’ (short accompanying film to the 2011 French documentary Bonobos).

And bonobo researcher Vanessa Woods gave this first-hand account of bonobos’ unlimited capacity for love from her study of them in their home in the Congo basin: ‘Bonobo love is like a laser beam. They stop. They stare at you as though they have been waiting their whole lives for you to walk into their jungle. And then they love you with such helpless abandon that you love them back. You have to love them back’ (‘A moment that changed me – my husband fell in love with a bonobo’, The Guardian, 1 Oct. 2015).

I should point out, as I did in Part 3 of THE Interview, that we couldn’t admit how nurturing was able to create cooperative, selfless and loving behaviour while we couldn’t explain how our conscious thinking mind became so upset and angry, egocentric and alienated, and as a result, so competitively, selfishly and aggressively behaved (which is what is all about to be explained), and as a result of that development lost the ability to adequately nurture our offspring with unconditional love. As I said in THE Interview about this situation, citing the lauded Australian writer and school teacher John Marsden, ‘parents would rather admit to being an axe murderer than a bad mother or father’! (Sunday Life, The Sun-Herald, 7 Jul. 2002). So, how nurturing gave us our cooperative, selfless and loving moral instincts is another of the critically important truths we couldn’t admit while we couldn’t present the explanation that is about to be given for our psychologically distressed, competitive, selfish and aggressive human condition—which, as I said in Part 3 of THE Interview, is why philosopher John Fiske’s 1874 recognition of how nurturing created our moral instincts has been ignored by human-condition-avoiding Reductionist Mechanistic science.

With regard to our own species’ time living in a cooperative, selfless and loving innocent state, as I also mentioned in Part 3 of THE Interview, way back in about 800 , the Greek poet Hesiod acknowledged this time in his epic poem Works and Days (the underlinings in quotes are my emphasis): ‘When gods alike and mortals rose to birth / A golden race the immortals formed on earth…Like gods they lived, with calm untroubled mind / Free from the toils and anguish of our kind / Nor e’er decrepit age misshaped their frame…Strangers to ill, their lives in feasts flowed by…Dying they sank in sleep, nor seemed to die / Theirs was each good; the life-sustaining soil / Yielded its copious fruits, unbribed by toil / They with abundant goods ’midst quiet lands / All willing shared the gathering of their hands’ (The Remains of Hesiod the Ascræan, tr. C.A. Elton, pp.17-18).

As I also included in Part 3 of THE Interview, Hesiod’s Greek compatriot Plato gave this similar description of our species’ time in innocence. In 360 , which is also a very long time ago, Plato wrote that ‘there was a time when…we beheld the beatific vision and were initiated into a mystery which may be truly called most blessed, celebrated by us in our state of innocence, before we had any experience of evils to come, when we were admitted to the sight of apparitions innocent and simple and calm and happy, which we beheld shining in pure light, pure ourselves and not yet enshrined in that living tomb which we carry about, now’ (Phaedrus; tr. B. Jowett, 1871, 250). I also included Plato’s other description of the innocent ‘‘Golden’ Age’ in our species’ past, where he wrote of a time when we lived a ‘blessed and spontaneous life…[where] neither was there any violence, or devouring of one another, or war or quarrel among them…In those days God himself was their shepherd, and ruled over them [in other words, our original instinctive self was orientated to living in an ideal, godly, cooperative, selfless and loving way]…Under him there were no forms of government or separate possession of women and children; for all men rose again from the earth, having no memory of the past [in other words, we lived in a pre-conscious state]. And…the earth gave them fruits in abundance, which grew on trees and shrubs unbidden, and were not planted by the hand of man. And they dwelt naked, and mostly in the open air, for the temperature of their seasons was mild; and they had no beds, but lay on soft couches of grass, which grew plentifully out of the earth’ (The Statesman, c.350 BC; tr. B. Jowett, 1871, 271-272).

These references from earlier times, when there wasn’t as much psychological upset in the world and thinkers were sounder and able to be more honest, do truthfully acknowledge the cooperative, selfless and loving innocence of our distant ancestors. They also recognised that these ancestors had a ‘calm and untroubled mind’ and ‘no memory of the past’; in other words, they weren’t yet conscious. As we are about to see, this development of a fully conscious mind in our distant ancestors (which, incidentally, the quotes about the bonobos evidence they are well on the way to developing) was immensely significant.

The following sequence of pictures and text summarise this truth that our ape ancestors, like bonobos, were cooperative, selfless and loving nurturers, not savage, barbaric brutes.

Our ape ancestors were innocent, loving, nurturers,

Paleoartist Jay H. Matternes’s unusually honest reconstruction of our ancestor, the 4.4 mya Ardipithecus ramidus, which appeared in the Dec. 2009 edition of Science, which the earlier mentioned report from C. Owen Lovejoy about our past ‘cooperative mutualism’ also appeared in. See Freedom Essay 22 for more on the fossil evidence of our nurtured past.

It is us humans now who are psychotic angry, egocentric and alienated, psychologically distressed, seemingly ‘evil’ monsters!

Detail from Jean-Michel Basquiat’s 1982 ‘Untitled’ painting which was sold in May 2017 for US$110.5 million, which, at the time was the sixth most expensive artwork ever sold at auction, no doubt because of its extraordinarily honest portrayal of the true nature of our present horrifically psychologically distressed human condition.

So nurturing is how we acquired our cooperative, selfless and loving instinctive self or soul, and, as I have said, these two truths of the importance of nurturing and of the existence of our cooperative, selfless and loving soul couldn’t be admitted while we couldn’t explain why we corrupted our soul—which is the explanation that is being given in this book.

Interestingly, the truth of the importance of nurturing in creating a sound, secure and well-adjusted human is recognised in Christianity’s description of Christ’s mother as being the ‘virgin mother’ (see Matt. 1:23 & Luke 1:26-34)—and it is also recognised in all the images in Christianity of the nurturing, loving ‘virgin mother and child’, like the drawing I have done below. To produce the extraordinarily innocent and sound Christ required an exceptionally innocent and sound nurturing mother, a metaphorically ‘un-fucked’ virgin mother. The explanation for why sex as humans have been practicing it under the duress of the human condition is actually an attack on women for their lack of empathy for men’s immensely heroic but immensely upsetting role in defying our instincts’ unjust condemnation in our species’ all-important search for knowledge (which is shortly going to be explained) is presented in chapter 8:11B of FREEDOM where the different roles of men and women in humanity’s journey is described. This underlying truth about sex was recognised by writer and activist Andrea Dworkin when she said, ‘All sex is abuse’ (Intercourse, 1987; reported in The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 Jul. 1987; see www.wtmsources.com/172). Importantly however, while sex has been an attack on the naivety of women, an act of aggression, it has also been one of the greatest distractions and releases of frustration and, on a nobler level, an inspirational act of love, an act of real affection derived from a shared faith in the ultimate meaning of the lives of men and women—which, as is going to be explained, has been to find the redeeming understanding of our corrupted human condition.

Jeremy’s 2006 tender drawing of the archetypal image of the Madonna and child. Jeremy has said about the image of the Madonna and child: “That this image is such a feature of Christian mythology is powerful recognition that it was the relatively alienation-free unconditional love Christ received from his mother that enabled him to be the exceptional denial-free, truthful thinking prophet that he was. When the great psychiatrist R.D. Laing wrote that ‘Each child is a new beginning, a potential prophet’ (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, 1967) he was recognising how much the upset, alienated world of humans today has corrupted our all-loving and all-sensitive instinctive self or soul. As the great playwright Samuel Beckett said about the brevity of innocence in the lives of most humans now: ‘They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more’ (Waiting for Godot, 1955)!”