‘FREEDOM’—Chapter 3 The Real Explanation of The Human Condition

Chapter 3:4 The Story of Adam Stork

What distinguishes humans from other animals is our fully conscious mind, our ability to understand and thus manage the relationship between cause and effect. However, prior to becoming fully conscious and able to self-manage—consciously decide how to behave—our earliest ape ancestors were controlled by and obedient to their instincts, as other animals continue to be. (Of course, humans are still apes, so when I say ‘ape ancestor’, I mean when we were like existing non-human great apes.) Aldous Huxley, author of famous novels such as Brave New World, acknowledged how other animals live, and also how our distant ancestors would have lived, obedient to their instincts, when he wrote, ‘Non-rational creatures do not look before or after, but live in the animal eternity of a perpetual present; instinct is their animal grace and constant inspiration; and they are never tempted to live otherwise than in accord with their own…immanent law. Thanks to his reasoning powers and to the instrument of reason, language, man (in his merely human condition) lives nostalgically, apprehensively and hopefully in the past and future as well as in the present’ (The Perennial Philosophy, 1946, p.141 of 352). I have underlined part of this passage because it raises the important question of what would happen if a species was ‘tempted to live otherwise than in accord with their own’ instincts—to, in effect, break that ‘immanent law’—as Huxley infers humans must have done when we became fully conscious? The following analogy involving migrating storks provides an illustration of what would happen.

Many bird species are perfectly orientated to instinctive migratory flight paths. Each winter, without ever ‘learning’ where to go and without knowing why, they quit their established breeding grounds and migrate to warmer feeding grounds. They then return each summer and so the cycle continues. Over the course of thousands of generations and migratory movements, only those birds that happened to have a genetic make-up that inclined them to follow the right route survived. Thus, through natural selection, they acquired their instinctive orientation.

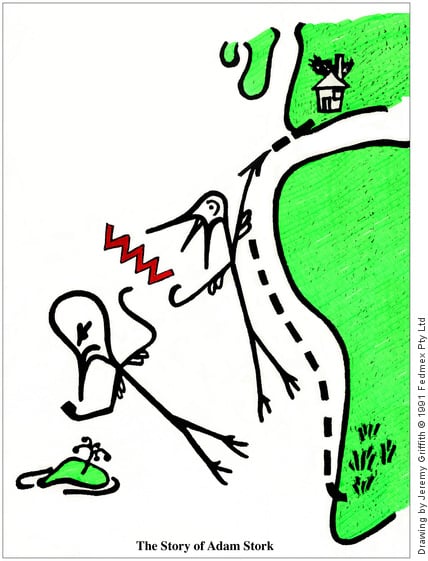

Consider a flock of migrating storks returning to their summer breeding nests on the rooftops of Europe from their winter feeding grounds in southern Africa. Suppose in the instinct-controlled brain of one of them we place a fully conscious mind (we call the stork Adam because we will soon see that, up to a point, this analogy parallels Moses’ pre-scientific account of the origin or genesis of the human condition in the Bible where Adam and Eve take the fruit from the tree of knowledge in the Garden of Eden). So, as Adam Stork flies north he spots an island off to the left with a tree laden with apples. Using his newly acquired conscious mind, Adam thinks, ‘I should fly down and eat some apples.’ It seems a reasonable thought but he can’t know if it is a good decision or not until he acts on it. For Adam’s new thinking mind to make sense of the world he has to learn by trial and error and so he decides to carry out his first grand experiment in self-management by flying down to the island and sampling the apples.

But it’s not that simple. As soon as Adam’s conscious thinking self (as depicted by the stork on the left) deviates from his established migratory path, his innocent instinctive self (as depicted by the wide-eyed stork on the right) tries to pull him back on course. In following the flight path past the island, the instinct-obedient self/stork is, in effect, criticising Adam’s decision to veer off course; it is condemning his search for understanding. All of a sudden Adam is in a dilemma: if he obeys his instinctive self and flies back on course, he will remain perfectly orientated but he’ll never learn if his deviation was the right decision or not. All the messages he’s receiving from within inform him that obeying his instincts is good, is right, but there’s also a new inclination to disobey, a defiance of instinct. Diverting from his course will result in apples and understanding, yet he already sees that doing so will make him feel bad.

Uncomfortable with the criticism his newly conscious mind or intellect is receiving from his instinctive self, Adam’s first response is to ignore the temptation the apples present and fly back on course. This ‘correction’ not only makes his instinctive self happy, it also wins back the approval of his fellow storks, for not having conscious minds they, like his instinctive self, are innocent, unaware or ignorant of the conscious mind’s need to search for knowledge. Furthermore, since Adam’s instinctive self developed alongside the natural world, it too reminds him of his instinctive orientation, thus contributing to the criticism of Adam for his rebellious decision.

Flying on, however, Adam realises he can’t deny his intellect. Sooner or later he must find the courage to master his conscious mind by carrying out experiments in understanding. This time he thinks, ‘Why not fly down to an island and rest?’ Again, not knowing any reason why he shouldn’t, he proceeds with his experiment. And again, his decision is met with the same chorus of criticism—from his instinctive self, from the other storks that were ignorant of the need to search for knowledge, and from the natural world. But this time Adam defies the criticism and perseveres with his experimentation in self-management. His decision, however, means he must now live with the criticism and immediately he is condemned to a state of upset. A battle has broken out between his instinctive self, which is perfectly orientated to the flight path, and his emerging conscious mind, which needs to understand why that flight path is the correct course to follow. His instinctive self is perfectly orientated, but Adam doesn’t understand that orientation.

In short, when the fully conscious mind emerged it wasn’t enough for it to be orientated by instincts. It had to find understanding to operate effectively and fulfil its great potential to manage life. Tragically, the instinctive self didn’t ‘appreciate’ that need and ‘tried to stop’ the mind’s necessary search for knowledge, as represented by the latter’s experiments in self-management—hence the ensuing battle between instinct and intellect. To refute the criticism from his instinctive self, Adam needed the understanding found by science of the difference in the way genes and nerves process information; he needed to be able to explain that the gene-based learning system can orientate species to situations but is incapable of insight into the nature of change. Genetic selection of one reproducing individual over another reproducing individual (the selection, in effect, of one idea over another idea, or one piece of information over another piece of information) gives species adaptations or orientations—instinctive programming—for managing life, but those genetic orientations, those instincts, are not understandings. This means that when the nerve-based learning system gave rise to consciousness and the ability to understand the world, it wasn’t sufficient to be orientated to the world—understanding of the world had to be found. The problem, of course, was that Adam had only just taken his first, tentative steps in the search for knowledge, and so had no ability to explain anything. It was a catch-22 situation for the fledgling thinker, because to explain himself he needed the very knowledge he was setting out to accumulate. He had to search for understanding, ultimately self-understanding, understanding of why he had to ‘fly off course’, without the ability to first explain why he needed to ‘fly off course’. And without that defence, he had to live with the criticism from his instinctive self and was INSECURE in its presence. (I should clarify that while instincts are hard-wired, genetic programming and as such cannot literally criticise our conscious mind, they can in effect do so. Our instincts let our conscious mind know when our body needs food, or, as our instinctive conscience clearly does, want us to behave in a cooperative, loving way, and certainly our conscious mind can defy those instinctive orientations if it chooses to. Our conscious mind can feel criticised by our instinctive conscience; it happens all the time.)

And so to resist the tirade of unjust criticism he was having to endure and mitigate that insecurity, Adam had to do something. But what could he do? If he abandoned the search and flew back on course, he’d gain some momentary relief, but the search would, nevertheless, remain to be undertaken. So all Adam could do was retaliate against and ATTACK the instincts’ unjust criticism, attempt to PROVE the instincts’ unjust criticism wrong, and try to DENY or block from his mind the instincts’ unjust criticism—and, as the stork on the left of the picture illustrates, he did all those things. He became angry towards the criticism. In every way he could he tried to demonstrate his self worth, prove that he is good and not bad—he shook his fist at the heavens in a gesture of defiance of the implication that he is bad. And he tried to block out the criticism—this block-out or denial including having to invent contrived excuses for his instinct-defying behaviour. In short, his ANGRY, EGOCENTRIC and ALIENATED state appeared. Adam’s intellect or ‘ego’ (which is just another word for the intellect since the Concise Oxford Dictionary defines ‘ego’ as ‘the conscious thinking self’ (5th edn, 1964)) became ‘centred’ or focused on the need to justify itself—selfishly preoccupied aggressively competing for opportunities to prove he is good and not bad, to validate his worth, to get a ‘win’; to essentially eke out any positive reinforcement that would bring him some relief from criticism and sense of worth. He unavoidably became angry, alienated and egocentrically SELFISH, AGGRESSIVE and COMPETITIVE.

Overall, it was a terrible predicament in which Adam became PSYCHOLOGICALLY UPSET—a sufferer of PSYCHOSIS and NEUROSIS. Yes, since, according to Dictionary.com, ‘osis’ means ‘abnormal state or condition’, and the Penguin Dictionary of Psychology’s entry for ‘psyche’ reads ‘The oldest and most general use of this term is by the early Greeks, who envisioned the psyche as the soul or the very essence of life’ (1985 edn), Adam developed a ‘psychosis’ or ‘soul-illness’, and a ‘neurosis’ or neuron or nerve or ‘intellect-illness’. His original gene-based, instinctive ‘essence of life’ soul or PSYCHE became repressed by his intellect for its unjust condemnation of his intellect, and, for its part, his nerve or NEURON-based intellect became preoccupied denying any implication that it is bad. Adam became psychotic and neurotic.

But, again, without the knowledge he was seeking, without self-understanding (specifically the understanding of the difference between the gene and nerve-based learning systems that science has given us), Adam Stork had no choice but to resign himself to living a psychologically upset life of anger, egocentricity and alienation as the only three responses available to him to cope with the horror of his situation. (And by alienation, it should be clear by now that I don’t mean alienation from society or some other group or individual, but the situation of being estranged or detached from our own instinctive self and any truthful thinking it inclines our conscious mind to pursue.) It was an extremely unfair and difficult, indeed tragic, position for Adam to find himself in, for we can see that while he was good he appeared to be bad and had to endure the horror of his psychologically distressed, upset condition until he found the real—as opposed to the invented or contrived not-psychosis-recognising—defence or reason for his ‘mistakes’. Basically, suffering upset was the price of his heroic search for understanding. Indeed, it is the tragic yet inevitable situation any animal would have to endure if it transitioned from an instinct-controlled state to an intellect-controlled state—its instincts would resist the intellect’s search for knowledge. Adam’s uncooperative and divisive competitive aggression—and his selfish, egocentric, self-preoccupied efforts to prove his worth; and his need to deny and evade criticism, essentially embrace a dishonest state—all became an unavoidable part of his personality. Such was Adam Stork’s predicament, and such has been the human condition, for it was within our species that the fully conscious mind emerged.

What now needs to be explained is how the situation faced by humans when we began searching for knowledge was so much worse than it was for our hypothetical Adam Stork. This is because, as was emphasised in chapters 2:5 to 2:7, our instinctive orientation wasn’t to a flight path but to behaving in an unconditionally selfless, all-loving, cooperative moral way, so when we started carrying out experiments in understanding and then unavoidably began reacting defensively in an angry, aggressive, competitive, selfish and evasive, dishonest way to combat the criticism from our instincts, that divisive response drew even more criticism from our particular cooperative, loving, ideal-behaviour-demanding, integrative, ‘very essence of life’-orientated moral instinctive self or soul or psyche—a vicious cycle that fuelled our upset immensely. (Chapter 5 will present the biological explanation of how humans acquired such unconditionally selfless, universally loving, moral instincts, the ‘voice’ of which is our conscience.)