Video & Transcript of

‘Extracts of Jeremy Discussing Various Topics’.

This video is a collection of Jeremy Griffith discussing various

topics with focus groups in Sydney in November 2014

1. A Short Extract about the Snake Phobia Analogy

Jeremy Griffith: So, how do I reconnect the reader to this historic fear of the human condition, because unless I can do that, they’re not going to be in a position to follow the argument and make sense of human behaviour and reach this deeper understanding that, supposedly, is explained in chapter 3 of FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition [see also Video/Freedom Essay 3]. So that’s my dilemma, my problem in the presentation. [See also Video/F. Essay 11.]

Imagine a tribe of people who suffer from a phobia of snakes, but they’re not aware of that, and when I ask them, ‘Why you do live indoors all day long?’ they say, ‘Well, we like carpet, we like square walls and walking through doorways. And, in fact, walking through doorways is what made humans stand up and become bipedal in the first place’! They’ve got all these theories based on their denial of their phobia.

So, I write a book about snakes to try and reconnect them to the fact that they have this phobia in order to help them heal from it. I show it to them, they open it, see it’s about snakes, shut it and say, ‘I’m not going to read that!’ Psychologically, that’s what happens, it’s impenetrable and I’m left scratching my head thinking, how the hell am I ever going to get them to benefit from this insight? Because this whole insight into their behaviour is based on them becoming aware that their phobia actually exists and until I can do that I’m not going to make any progress.

If I can connect humans with the possibility that they do actually suffer from this fear of the human condition we can begin to look at all the issues about our human behaviour from this perspective, that we’re living in fearful denial of the subject. Then you can follow the argument because you’ve got some sense of the possibility that we actually do suffer from this horrific fear. In fact, that’s what I do, FREEDOM begins with the best way I know of to connect people to the existence of this terrifying fear that we’re obviously living in denial of and can’t face, which is by explaining the process of Resignation [see F. Essay 30].

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

2. A Short Extract about the Adam Stork Analogy

We must have had an instinctive orientation like other animals once, before we developed a conscious mind some two million years ago. Then we developed a conscious mind which is a different sort of information processing system [see F. Essay 24]. It needs to understand cause and effect. The gene-based learning system can give a species orientation but it can’t provide understandings.

I use the example of migrating storks. They learn not to fly across the Sahara, not through any understanding but because the storks whose genetic make-up inclined them to fly that path got frizzled. So now, through natural selection, they all fly around the coast. They’ve got an instinctive orientation but it’s not an understanding. So imagine we were to put a conscious mind on one of these storks, as I explain in chapter 3 [see also Video/F. Essay 3], and we’ll call him Adam Stork because it’s similar to the story of the Garden of Eden but with a different ending. In the story of the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve take the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge, meaning they become conscious. Our human ancestors once lived in a Garden-of-Eden-like, pre-human-condition, innocent state. Then we ‘took the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge’—became conscious—and then in that story it says we’re evil and we get chucked out of the Garden of Eden. [You can read a short history of some of the many thinkers who have recognised the true ‘instinct vs intellect’ elements involved in the human condition in Video/F. Essay 4.]

So we’re going to watch Adam Stork, we’re going to give him a conscious brain then see what happens. So he’s flying along with the other storks and thinking to himself that he might fly down to an island, why not? He has no understandings yet, he’s got to find understanding by experimenting. So he heads down towards the island and you can see him hesitate because his instincts are going to try to pull him back onto the flight path that goes over the island. He’s in a dilemma; either he gives into his instincts and never finds knowledge or he courageously defies his instincts and perseveres with his search for knowledge. He’s got to have the courage to persevere in spite of his instincts being intolerant of his need to search for knowledge.

So the only way old Adam Stork can cope with the criticism is to block it out, get angry with his instincts and try to prove them wrong, prove that he’s not bad. He becomes angry, eccentric and alienated which is the essential state of our corrupted human condition. But if you stand back and look at that story, who’s the hero? Old Adam Stork who had to have the guts, the courage to persevere. As it says in the song The Impossible Dream, which featured in the 1965 musical about Don Quixote, Man of La Mancha, we had to be prepared ‘to march into hell for a heavenly cause’ (Joe Darion, The Impossible Dream, 1965). The human condition is very paradoxical—we had to lose ourselves to find ourselves—we had to ‘march into hell’, suffer becoming corrupted in order to find the understanding that would end our corruption. Old Adam Stork was never going to free himself from this condemnation until he could sit down with his instincts and explain, using first principal biological explanation, why he had to fly off-course: ‘So, do you get it instincts? I’m good and not bad after all, get off my case, okay?’

No longer does he have to get angry and block out these criticisms because he’s defended. That’s why chapter 3 of FREEDOM will transform you because it will provide the explanation that we’ve been in search of since we first became conscious beings. [See F. Essay 15 for more on the Transformation that is now possible.]

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

3. A Short Extract about Resignation

Just to go through Resignation, and there are lots of different examples of it in FREEDOM [see chapter 2:2, and also F. Essay 30]. The first example is from Robert Coles, the American Pulitzer Prize-winning child psychiatrist, who wrote about children going through Resignation. Once you resign and decide never to look at the subject again—and most adults have been through this tight corner when they’re around 15 years old—then you’re part of the problem, you’re on an escapist trip, you’re not going to go and look any deeper again. Kids start thinking about the human condition and they know adults can’t relate to them so they’re in their room with their earphones on going crazy, wrestling with the human condition. Their parents love them and they love their parents but they know, for some reason, no one is talking about this subject, it’s off limits. But they’re still looking at it, they can still see the imperfections of human life. So Robert Coles wrote this really powerful little piece. In my view, any great literature or poetry or music or art is only really great if it ventures near the truth of the human condition and I wouldn’t be surprised if Robert Coles didn’t receive the Pulitzer Prize for this one particular paragraph. The honesty in it is so beautiful and so precious. So I’ll just quickly go over it.

What happens to kids when they’re in their late childhood stage, about eight, is they’re actually starting to encounter the imperfections of life under the duress of the human condition and they’re starting to get frustrated by it. You get the ‘naughty nines’ when they start to lash out at the world in frustration at the imperfection, chaos and madness. But by around 12 years old something very significant happens psychologically. They actually change pace, they realise that flailing out at the world is getting them nowhere and they’re going to have to sit down and try to make sense of why the world is so imperfect. Why is there all this artificiality, madness, chaos, anger, frustration, selfishness and meanness? They can still see it because they haven’t resigned yet, haven’t committed themselves to blocking out the issue of the human condition. So for them, it’s right there and they can see it starkly.

So they change from being protesting, demonstrative, extroverted children to sobered, introspective, introverted adolescents. We actually change the description from ‘childhood’ to ‘adolescence’. Have you ever thought why? It’s because something big is happening psychologically. Teachers hate teaching nine and ten year olds, but when they get to 12 years old there’s a huge change. They’re easy to handle, they’re immensely manageable and there’s a reason for that which is that they change from protesting to trying to figure out why the world isn’t right.

So they start thinking deeply about the imperfections of human life and they keep thinking about it and it progresses from thinking about the imperfections in the world to gradually starting to focus, not only on the human condition without, but the human condition within—their own imperfection. Because they’ve entered into the world of the human condition and suffer all the same imperfections, so they’re full of anger and egocentricities, indifferences, meanness and selfishness. There’s a huge amount of imperfection in their own lives and when they try to face that, it’s suicidally depressing. It’s unbearable without the explanation of the human condition, which is what chapter 3 of FREEDOM presents [see Video/F. Essay 3]. If you haven’t got the answers what you’re facing is, ‘we’re a rotten species and I’m rotten as well. I’m a bad, evil person’, and that’s unbearable if you try to face it with honesty and without any defence system. If you’re still capable, the door’s still open and you’re truthful, that will lead to suicidal depression. That’s how terrible the issue of the human condition is if you don’t have any defences protecting you, and children haven’t learnt them yet, each generations has to go through this process.

Catherine Yeulet/iStockphoto; yamasan/AdobeStock; Al Troin/AdobeStock

So children lock themselves in their room grappling with all of this which is what Coles is talking about in the following: ‘I tell of the loneliness many young people feel…It’s a loneliness that has to do with a self-imposed judgment of sorts…[they’re starting to confront the human condition within themselves] I remember…a young man of fifteen who engaged in light banter, only to shut down, shake his head, refuse to talk at all when his own life and troubles became the subject at hand. He had stopped going to school…he sat in his room for hours listening to rock music, the door closed…I asked him about his head-shaking behavior: I wondered whom he was thereby addressing. He replied: “No one.” I hesitated, gulped a bit as I took a chance: “Not yourself?” He looked right at me now in a sustained stare, for the first time. “Why do you say that?” [he asked]…I decided not to answer the question in the manner that I was trained [basically, ‘trained’ in avoiding what the human condition really is]…Instead, with some unease…I heard myself saying this: “I’ve been there; I remember being there—remember when I felt I couldn’t say a word to anyone”…The young man kept staring at me, didn’t speak…When he took out his handkerchief and wiped his eyes, I realized they had begun to fill’ (The Moral Intelligence of Children, 1996, pp.143-144 of 218). What had happened was that Coles had reached him with some honesty about what he was wrestling with, when he’d given up on anyone ever recognising it, some honesty about what he could see which is the struggle, the horror of the utter hypocrisy of human behaviour, and that little bit of honesty saved his life. It was so precious to him that he started to cry.

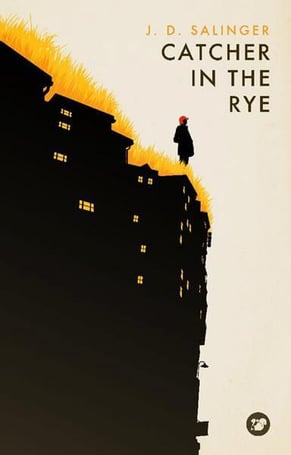

One of the most famous books in American literature is J.D. Salinger’s 1951 novel The Catcher in the Rye, which you’ve probably read when you were kids, it’s an absolutely wonderful book. It’s about a 16-year-old boy, Holden Caulfield, struggling against Resignation. He’s in total protest, saying he’s ‘surrounded by phonies’ (p.12 of 192) and ‘morons’ who ‘never want to discuss anything’ (p.39)—they’re artificial and dishonest, they’re pretending. Because when you resign you’re never going to go down that road again, even two days after someone has hit that corner they’ve decided never to revisit it because it’s so depressing. They can hardly remember that they were so terrified by that dark corner. So they’re on an escapist mission ever after—more parties, don’t think, just escape. So post-Resignation our whole attitude changes, instead of being honest and thoughtful and profound we become escapist, evasive, seeking power, fame, fortune and glory. Anything to prove our self-worth in the form of artificial reinforcement because we can’t get real reinforcement, we can’t understand ourselves. So I’m coming along now and presenting the actual understanding.

But you’ve got to remember that all the books we’ve got, and there are mountains of them, libraries of them at the universities just outside this window, they’re all written from inside the cave, in denial of the human condition, not wanting to face the human condition. [See Video/F. Essay 11 for a description of Plato’s Cave allegory.] So they’re going to be very artfully escapist and not really honest. [See Video/F. Essay 14 for a description of the dishonesty in mechanistic science.] When you’re unresigned you can tell that the world is all bullshit, that they’re not being fair dinkum, everyone’s on a mission to escape the human condition not confront it, they’re not really wanting to be honest at all. So you’ve got this perfect shit-detector when you’re an unresigned kid. You’ve got to get this book to pre-resigned adolescents because they’ll soak it up, they’re desperate to get some real answers.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

4. A Short Extract about Truth in the Arts

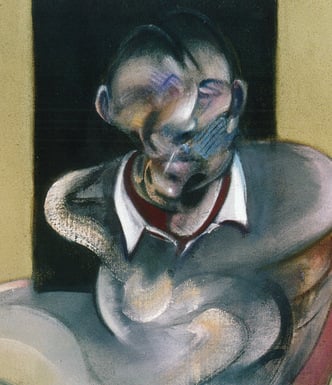

Great literature or art is where, I suggest, people have dared to go near the fire, this forbidden subject of the human condition and bring some truth to it, some relief and honesty to it [see F. Essay 44 and F. Essay 31]. So, as I said, this self-portrait by Francis Bacon, is a portrait of the human condition. It’s frightful, the face is running together, it’s unmistakable, the agony of the human condition. Bacon’s twisted, smudged, distorted and death-mask-like, alienated, trodden on, tortured, contorted, stomach-knotted, arms pinned, psychologically strangled and imprisoned bodies and that sold at auction for $US142.4 million, breaking the record set by Edvard Munch’s The Scream, which is obviously another picture of the human condition. So, the work of art that fetched the highest price ever at auction was by someone being truthful about the human condition.

People look at Bacon’s pictures and say they’re ‘enigmatic, he’s got a dark view of the world and I can’t relate to that, he must have had a really bad morning when he painted that’. But if you think deeply about that, why are people saying that this is worth so much money? Because underneath our denial we actually know what’s true and what isn’t and we know that what he’s done there is pretty accurate. That’s how messed up we are.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

5. A Short Extract about Communism and Capitalism

Adrianna: My son read The Communist Manifesto just two weeks ago because his older sister told him, you should read it if you want to know history. That if you really want to know history you have to start with this.

Jeremy: Yeah.

Adrianna: And he did, and then he came back talking like, ‘Oh my God, I’m glad you told me and I’m glad I read it!’ So yeah, that’s the age when they really actually read this stuff.

Jeremy: Searching for some truth. So does The Communist Manifesto have some real truth in it, is that what you’re saying?

Adrianna: Well, I’m not very big on history but three of my kids, they like history a lot and he has two older sisters and he tries to learn from them, what they go through and how did they make it easier for themselves. I have read it for myself when I was in high school so.

Jeremy: Yeah, but is there something very authentic in that?

Adrianna: It is! It is very small but actually it has so much truth in there.

Jeremy: Well let’s imagine, I haven’t read it, but I can imagine what’s in it, which would be that if everyone cooperates and shares and is selfless and considerate of each other, the world will be a better place, right? And for an unresigned adolescent, that would be truthful. [See F. Essay 30 for an explanation of Resignation.] They are asking; why is the world so mean and selfish and brutal? So that would represent some idealism that they could identify with, you can understand that. But you’ll read in chapter 3 of FREEDOM [and Video/F. Essay 3] that we/Adam Stork had to fly off course to search for knowledge, suffer becoming angry, egocentric and alienated and then when we have become upset we’ve got to have something to sustain us while we’re living in that state of dishonesty. Adam Stork needs artificial reinforcement, he needs materialism, he needs to feel good about himself, he needs a nice cut suit, he needs some defiant, white Marlon Brando shirt, or nice jewellery or a lovely dress. We need our materialism to makes us feel better about ourselves while we couldn’t defend ourselves.

Adrianna: Definitely, yes.

Jeremy: So materialism has a very important role to play, and capitalism or money was needed to supply that materialism. So once you admit that we did have to fly off course, did have to suffer becoming angry, egocentric and alienated then we needed materialism. It’s justified that we had to have a few chandeliers in our lives. Sure, it caused inequality. I mean, this watch I’m wearing could probably feed a mob of starving Ethiopians, it’s only a Swatch watch but we’re full of dishonesty and fraudulence.

So you can imagine The Communist Manifesto would be very appealing to a pre-resigned adolescent who hasn’t yet bought into the whole need for escapism and materialism. However, chapter 3 explains that this is in defence of materialism because, while we couldn’t have real spiritualism, spiritualism, meaning mind nourishment, understanding of our condition, all we had was material forms of reinforcement; a big house, a big car, a good suit to make us feel better about ourselves. Chapter 3 defends humans and tells us we’re good and not bad, and makes sense of that. So movements like communism, socialism and Marxism, they were actually false starts to an ideal world [see F. Essays 34 and 35]. Adam Stork can’t fly back on course and give up the search for knowledge, he can’t stop ‘march[ing] into hell for a heavenly cause’. He had to find explanation of the ‘heavenly cause’ which is the understanding that would defend him and then, and only then, would it be legitimate to fly back on course and become ideally behaved, give up the corrupting search for knowledge. We had to suffer becoming upset in order to find sufficient knowledge to explain ourselves.

So materialism has a very important role to play. We can understand that about ourselves now, the need for some luxury, comfort and relief from the agony of the human condition. But when it got really extreme people like Marx are going to pop up saying, ‘Look, enough’s enough, there’s too much greed here, everyone share’ and everyone ticks that box and says, ‘yeah, we’ll all share, it’ll be great!’ But you haven’t gotten rid of the human condition so people are going to start sharing but they’re still going to be mean and twisted and unhappy and suffering with the human condition inside. So after a while they’re going to start ripping the system off and selling their potatoes behind the scenes in exchange for money and the whole communal system will collapse because they haven’t found the dignifying understanding that’ll allow it to end.

So these are false starts to the human-condition-free world; the only way we’re ever going to get there is through knowledge, understanding of ourselves. That’s why the ancients had emblazoned across their temples the phrase, ‘Man, know thyself.’ We need brain food, not brain anaesthetic. Stopping the brain from thinking is to deny what we are—human. We’ve got to find knowledge, we’ve got to get out of this cave by finding understanding. We want answers, we want brain food.

So that’s what this book is all about, supplying answers.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

6. A Short Extract about Heavy Metal Music

Jeremy: So this is the heavy metal band With Life In Mind and clearly these are the words of an unresigned adolescent who hasn’t given in yet and become fake and phony [see F. Essay 30: Resignation]. He’s seeing the world for real. So this is a real description of our world from someone who can still see it the way it really is. When we are resigned we can’t see it like it is. These are terrifying words but they are dead accurate, like R.D. Laing who rolled around drunk as a skunk rather than complying with the world of denial. He said, ‘look mate, I’m just going to tell the truth because someone’s got to tell some truth around here’. [See F. Essay 48 for more on R.D. Laing.]

So these are some of the lyrics from With Life In Mind from their 2010 Grievances album: ‘It scares me to death to think of what I have become [so, he’s being very honest about himself]…I feel so lost in this world’, ‘Our innocence is lost’, ‘I scream to the sky but my words get lost along the way. I can’t express all the hate that’s led me here and all the filth that swallows us whole. I don’t want to be part of all this insanity. Famine and death. Pestilence and war. [Famine, death, pestilence and war are traditional interpretations of the ‘Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse’ described in Revelation 6 in the Bible. Christ referred to similar ‘Signs of the End of the Age’ (Matt. 24:6-8 and Luke 21:10-11).] A world shrouded in darkness…Fear is driven into our minds everywhere we look’, ‘Trying so hard for a life with such little purpose…Lost in oblivion’, ‘Everything you’ve been told has been a lie [just as R.D. Laing said]…We’ve all been asleep since the beginning of time. [again, almost the same as R.D. Laing] Why are we so scared to use our minds?’, ‘Keep pretending; soon enough things will crumble to the ground…If they could only see the truth they would coil in disgust’, ‘How do we save ourselves from this misery…So desperate for the answers…We’re straining on the last bit of hope we have left. No one hears our cries. And no one sees us screaming’, ‘This is the end.’

‘So desperate for the answers’. So that’s an unresigned mind talking to us about all that he could see about the madness of the world which we can no longer see, since we’re on the other side of Resignation.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

7. A Short Extract about our Conscience and Evolutionary Psychology

Jeremy: That is what we would say would be our conscience [see chapter 5 of FREEDOM, and F. Essay 21]. We could all work out rationally that ideally it would be better if everyone was cooperative, loving and selfless. That is a fairly obvious ideal and so you could say we’ve got a conscious, a moral self just from rationally looking at the ideal situation which would be everyone being cooperative and loving. Like communism which says we should share everything. But it’s universally accepted that we’ve got an altruistic moral nature, an instinct which our conscience is the voice of, the expression of within us. So we are born with this instinctive propensity to be selfless, like the example I gave in FREEDOM, par. 380, of the professional footballer Joe Delaney who admitted that ‘I can’t swim good, but I’ve got to save those kids’, just moments before plunging into a Louisiana pond and drowning in an attempt to rescue three boys (‘Sometimes The Good Die Young’, Sports Illustrated, 7 Nov. 1983).

So, yeah, it is universally accepted that we’ve got this moral nature but how did we acquire it? That’s the great mystery, because all these biological theories are actually human-condition-avoiding theories. That’s why chapter 5 is so important because it presents the explanation of how we acquired our altruistic moral instincts without using a human-condition-avoiding explanation [see also F. Essay 21]. That’s what I was trying to explain in my talk to you, that once you understand that humans are living in fear of the human condition, in this metaphorical cave of denial [see Video/F. Essay 11], you can see why they developed all these theories that want to avoid the human condition, not confront it. They are dishonest theories, and I just gave you an example of Evolutionary Psychology which says that bees give their life because they’re fostering their own reproduction by fostering the queen [see Video/F. Essay 14 for a description of dishonest biological theories purporting to explain our moral conscience].

Craig: Yep.

Jeremy: But then to extrapolate that and say that when we behave selflessly towards others, like the footballer who gave his life trying to save those kids, we’re trying to foster our genes in those that are related to us, doesn’t make sense because in that example, those kids obviously weren’t related to him. They would say that’s just an aberration of the basic idea but obviously there is a huge flaw in that argument. So what happened then, as you’ll read in chapter 2, is that they switched to another shonky theory which E.O. Wilson had come up with, saying, ‘we’ve used that Evolutionary Psychology lie long enough, it isn’t working, let’s find another one’. The Multilevel Selection theory for eusociality is even cleverer but it is still avoiding the human condition [again, see Video/F. Essay 14].

So if you go to chapter 5, supposedly it will explain the real reason for how we acquired our moral nature in a human-condition-confronting, truthful manner and that is the thesis of the whole book: to establish that humans are living in denial and can’t face the truth of the human condition so everything they are saying and all their theories are human-condition-avoiding, right?

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: And then it goes through and looks at all these big questions and, by not avoiding the human condition, makes sense of them.

So, what happens when you get to chapter 5? It answers this massive question: How did we acquire our unconditionally selfless moral nature, that our conscience is the expression of, that we’re all born with? And the answer is through nurturing, and the bonobos provide us with a living example of this occurring. [Again, see F. Essay 21.]

Craig: Right.

Jeremy: Now the reason this nurturing explanation has been human-condition-avoided and never been admitted, well, it was actually put forward as a developed theory by the philosopher John Fiske in his 1874 book, Outlines of Cosmic Philosophy: based on the Doctrine of Evolution about three years after Darwin’s work was published and it was actually described as a theory far more important than Darwin’s principal of natural selection [see par. 488 of FREEDOM and F. Essay 20]. But Fiske’s theory was left to die due to our fear of the human condition, because if it’s true that nurturing made us human, and that nurturing is, therefore, the most important ingredient in our development from infancy to adulthood, it confronts parents with their present inability to nurture their children as much as they were nurtured before the human condition emerged. So as I say in FREEDOM, parents would rather admit to being an axe-murderer than a bad parent. So it’s an unbearable truth. First, we need to explain the human condition, the good reason for our upset corruption and then we can safely admit all these other truths.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

8. A Short Extract about the Honesty of R. D. Laing

Jeremy: This is how honest R.D. Laing is [see also F. Essay 48]. He’s this wild psychologist. Harry Prosen, who wrote the wonderful Introduction to FREEDOM was in charge of his university’s psychology department and Laing once came to give a talk. He was absolutely rotten drunk and he staggered around on the stage and fell over which was so embarrassing for everybody. But that’s how honest this guy was. I absolutely love him because he let the truth out, he was just fearless. [See also F. Essay 47 on swearing and humour.] He said, ‘look I just see so much suffering every day’ with all these people coming in and needing psychological help and he’s a brilliant psychologist. He used to get down on the floor and have these empathetic experiences with his patients because he shared their pain, they were crawling with pain and he could reach them. Harry Prosen is like that, you can read some stories in FREEDOM about how empathetic he is.

R.D. Laing was fearlessly honest but he was self-destructive because he was so honest, he just couldn’t care less. This is what he said about humans, ‘Our alienation goes to the roots. The realization of this is the essential springboard for any serious reflection on any aspect of present inter-human life [p.12 of 156] [He’s saying that if we don’t recognise this alienation, this state of denial, we’re not going to get anywhere. So he’s saying exactly what Plato said, that we’re living in a cave and you’ve got to live outside the cave to be able to see the truth] …the ordinary person is a shrivelled, desiccated fragment of what a person can be [p.22] …The condition of alienation, of being asleep, of being unconscious, of being out of one’s mind, is the condition of the normal man [p.24] …between us and It [our true selves or soul] there is a veil which is more like fifty feet of solid concrete. [p.118] [We’re not going to go near that subject ever again] The outer divorced from any illumination from the inner is in a state of darkness. We are in an age of darkness. The state of outer darkness is a state of sin—i.e. alienation or estrangement from the inner light [p.116] …We are all murderers and prostitutes…We are bemused and crazed creatures, strangers to our true selves, to one another’ [pp.11-12] (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, 1967). ‘We are dead, but think we are alive. We are asleep, but think we are awake. We are dreaming, but take our dreams to be reality. We are the halt, lame, blind, deaf, the sick. But we are doubly unconscious. We are so ill that we no longer feel ill, as in many terminal illnesses. We are mad, but have no insight [into the fact of our madness]’ (Self and Others, 1961, p.38 of 192). ‘We are so out of touch with this realm [where the issue of the human condition lies] that many people can now argue seriously that it does not exist’ The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, 1967, p.105)

That is what I’m trying to break through, the ‘fifty feet of solid concrete’ to this realm that everyone is living in denial even exists, and reconnect us because once I can do that then I can go through and unpack everything and you’ll be astonished. So I’ll take on all these great issues and I’ll explain them but from a non-denial, human-condition-confronting, honest perspective and it’ll all unravel.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

9. A Short Extract about ‘The Catcher in the Rye’ and Adolescence

Jeremy: The Catcher in the Rye is this amazing story, it’s the most wonderful story to read, so magically written because he takes this boy Holden Caulfield and gives him the voice of a frustrated, lonely teenager, it’s just unbelievable stuff [see also F. Essay 30].

Holden Caulfield, complains of feeling ‘surrounded by phonies’ (p.12 of 192) and ‘morons’ who ‘never want to discuss anything’ (p.39), of living on the ‘opposite sides of the pole’ (p.13) to most people, where he ‘just didn’t like anything that was happening’ (p.152), because it’s all so fraudulent and dishonest, to wanting to escape to ‘somewhere with a brook…[where] I could chop all our own wood in the winter time and all’ (p.119). He knows he is supposed to resign—in the novel he talks about being told that ‘Life…[is] a game…you should play it according to the rules’ (p.7), and to feeling ‘so damn lonesome’ (pp.42, 134) and ‘depressed’ (multiple references) that he felt like ‘committing suicide’ (p.94). As a result of all this despair and disenchantment with the world he keeps ‘failing’ (p.9) his subjects at school and is expelled from four for ‘making absolutely no effort at all’ (p.167). About his behaviour he says, ‘I swear to God I’m a madman’ (p.121) and ‘I know. I’m very hard to talk to’ (p.168), because he is living in a different paradigm to everybody else. He’s still saying, ‘you’re all fake and phony and no one is admitting it and you’re all laughing and making jokes, saying let’s go to a party, buy some more blue shoes, blah, blah, blah, blah, no one’s being fair dinkum here’.

But like the boy in Coles’ account [see Extract 3 above, and F. Essay 30], Holden finally encounters some rare honesty from an adult that, in Holden’s words, ‘really saved my life’ (p.172). This is what the adult said: ‘This fall I think you’re riding for—it’s a special kind of fall, a horrible kind…[where you] just keep falling and falling [utter depression]’ (p.169). The adult then spoke of men who ‘at some time or other in their lives, were looking for something their own environment couldn’t supply them with…So they gave up looking [they resigned]…[adding] you’ll find that you’re not the first person who was ever confused and frightened and even sickened by human behavior’ (pp.169-170). That’s the key line in the whole book because to be ‘confused and frightened’ to the point of being ‘sickened by human behavior’—including your own behaviour, indeed, to be ‘suicid[ally]’ ‘depressed’ by it—is the effect the human condition has if you haven’t resigned yourself to living a relieving but utterly dishonest and superficial life in denial of it. That adult saved Holden’s life, it made all the difference because every day he is running into adults, looking at them, and saying, ‘can’t you see what I can see?’ And they can’t and it’s driving him crazy, but one day somebody is a little bit honest with him and that damn well saves his life. The book is called The Catcher in the Rye because at the end of the book Holden has this vision: ‘I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff—I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be’ (p.156)

So he’s saying, ‘I just want to be the catcher in the rye who stops the kids from having to resign, having to die inside’, because when you resign you give up thinking truthfully, you’re going to be fake, artificial and superficial thereafter. There is a huge elephant in our living room which is this issue of the imperfection of life—the human condition—and no one is even admitting it but it’s filling the whole damn room. It’s the real subject which is what I said at the beginning, to explain human behaviour you have to talk about this bloody elephant, but no one is even aware that it’s there.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

10. A Short Extract about Where Thinking Can Lead Our Minds

Jeremy: This is what happens after Resignation [see also F. Essay 30] because any thinking is going to bring you into contact with the human condition. I used the example: There is a lovely tree or a wonderful sunrise, you start thinking about that and you think, ‘Gee, it’s amazing how beautiful nature can be’, the next thought is, ‘I wonder why I’m not beautiful inside but rather full of angst, indifference to others, meanness, frustration and anger’, which leads to ‘aarrrgggghhhhh!!!!’. Then you’re back confronting the human condition.

William Wordsworth was making this point when he wrote, ‘To me the meanest flower that blows can give thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears’ (Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood, 1807). [See F. Essay 31: Wordsworth’s majestic poem.] Those ‘thoughts’ are so profound and unsettling, it’s true that even the plainest flower can remind us of the unbearably depressing issue of our seemingly horribly imperfect human condition. As the comedian Rod Quantock once said, ‘Thinking can get you into terrible downwards spirals of doubt’ (‘Sayings of the Week’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 Jul. 1986).

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

11. A Short Extract about Religions and Pseudo-Idealism

Jeremy: One way to stop us from behaving so aggressively was for us to stop living through our upset conscious state and defer to something that was supposedly more honest than we were and live through that. So that was religion—you could defer to a great prophet who clearly wasn’t full of upset and through him you could find yourself at peace again because you’re not living out your upset [see F. Essays 34 & 39]. The criticism of people like Genghis Kahn or Hitler would be that they didn’t become deeply religious in that sense.

Sure, religions became fanatical and the whole thing got out of control again later on but religions have been the least dishonest form of pseudo idealism because of the honesty of the prophet that the religion was founded around. But religion did eventually become too condemning, too confronting because of the emphasis on guilt that resulted from that honesty. People got sick of that, and then we got into these even more pseudo-idealistic movements [see F. Essay 35]. They’re not genuinely idealistic because we’re still very upset. It’s like Ned Flanders from the cartoon series The Simpsons whose a born-again Christian, he’s a goody-goody but his neighbour Homer Simpson is still out there trying to conquer the world, he’s still in full flight. So Ned is actually even more upset than Homer but he’s found his faith that he lives through rather than living through himself, so he defers to that and finally he’s a force for good.

Then we’ve got Environmentalism which doesn’t have the guilt involved and you can save a tree or a threatened species and feel good about that. We’ve become so desperate to find some relief from the guilt, from the human condition, that you get the situation where people are doing good for the ulterior motive of making themselves feel good, to relieve themselves of the human condition. So there’s a subtlety there that comes in later on but the fundamental situation is our goody-goody instincts condemned our conscious mind’s search for knowledge and we unavoidably have to become defensive and retaliatory and egocentric and so on. So our instincts are criticising us there but when you’re born again later on, at the very end of this horrific journey with ever increasing levels of upset, it gets so bad that people start doing good, not because their responding to their instincts telling them to be good but because they want to feel good to relieve their sense of guilt. They want relief from the human condition. It’s a very different equation. The whole thing gets compounded and one level of upset is happening on top of another. The last eleven thousand years, with agriculture and the domestication of animals which allowed people to settle and multiply and form towns and cities where closer interaction amongst humans had the effect of rapidly escalating upset, and then even more so in the last two hundred years which is the final section of chapter 8 [chapter 8:16 ‘The last 200 years during which pseudo idealism has taken humanity to the brink of terminal alienation’], is really where upset goes through the roof and everyone is on an absolute bender to try to find some escape from who they are, from the darkness inside themselves. They find enormous relief in taking up some moral cause that might make them feel some sense of goodness if they’re feeling that dark about themselves. If you find a cause, like saving the environment, the rush you get from being good at last is very relieving.

So the point is that there were false starts to the free world. In the Adam Stork situation, at anytime Adam could fly back on course, obey his instincts (in our case, our moral, cooperative and loving instincts) [see F. Essay 21] and feel good about himself, but that would actually be irresponsible because he would be giving up his search for knowledge. That is the problem with pseudo-idealism. In FREEDOM I argue that religion saved humanity because it gave us a way to defer to something greater than ourselves when we could no longer afford to live out who we were because we were so destructive, so upset, but it’s a false form of idealism because our real self hasn’t healed at all. We’re just giving up on letting it have its day.

So if Homer could explain himself to Ned, he’d say, ‘Listen Ned you’re a goody-two-shoes, God loves you and you love God but I’m not giving up. I’m going to Las Vegas next week, I’m going to party up. I’m giving Lisa a hard time and Bart an even worse time but I’m out there doing it, mate. I’m Adam Stork, flying off course, I’m still participating in the heroic search for knowledge.’ Interpreted with the understanding in chapter 3 of FREEDOM, you can see that old Homer is being driven crazy by Ned because he’s a goody-goody and he’s got this really conceited, moral high ground and he looks down on Homer. Homer borrows Ned’s lawnmower and smashes it up and doesn’t tell him, it’s all just crazy because there’s no reconciling understanding between them. Homer knows intuitively that Ned’s bullshitting, that he’s not really sound, it’s the opposite, he’s actually deferring to Christianity because he’s unsound and deluding himself, but Homer can’t explain it.

That’s what happens when you can finally explain the human condition, you can finally reveal the real game plans going on behind everything but it’s actually compassionate. Ned can respond to Homer now by saying, ‘well, that was the responsible thing for me to do when I became so upset. I had to find something that I could live through that would save me from myself, and you’re so destructive Homer that maybe you should give religion some decent thought.’ But what you’ll read in chapter 9 [see also F. Essay 15] is that there’s a new way of coping. We don’t have to resort to these false, pseudo-idealistic ways of feeling good about ourselves. We can actually ameliorate or heal the confusion in our mind and subside it, which is what Anna was saying is happening at a rapid rate for her, so much so she’s feeling that she needs to slow up and let it all go through the filters. And Bartholomew’s opening comment today was, ‘you’ve got to make this video available to everybody trying to read this book, it’ll help a lot.’

We’ve wanted a real form of relief from the pain in our brains, something that made sense. I was saying to Craig, he has a very rigorous mind, he’s not going to take a step that doesn’t stack up so he’s got these fundamental questions and they’re really good questions. And I said, you shouldn’t move one inch on anything until you’re totally satisfied that it actually works, but I’ve got no fear because he’s extremely rational and cautious and sceptical which is great. But this either stacks up or it doesn’t.

That was one question about people doing the right thing because they’re obeying their instincts but it’s complex because people do it now for a different reason, to feel good, so it can be hard to see through what they’re doing.