Video & Transcript of Further Responses from the Public to FREEDOM from Focus Groups held in 2014

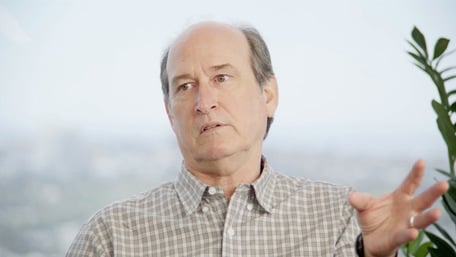

In November 2014 Jeremy Griffith gave a number of introductory presentations to focus groups in Sydney. This video is a collection of responses that were not included in the 2014 Focus Group Introductory Talk.

The context for these responses was that participants were first asked to read chapter 2 of FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition, then listen to an Introductory talk focusing on the problem of the ‘deaf-effect’ when reading about the human condition, before finally being asked to read chapter 2 again, but this time with chapter 3 as well.

Extracts

Nancy: It’s quite big, I feel. Like you can understand a lot of the things you could never understand back then [as an adolescent during Resignation—see Freedom Essay 30 for an explanation of Resignation].

Anna: It really gripped me, I didn’t expect it to.

Marvin: I was really interested. It really spoke to me.

Richard: It’s certainly confrontational. It’s material and ideas that I’ve not come across before, I’ll be honest, and it’s leading one to take a view of the world quite contrary to the one that I spent 50-odd years growing up with.

John: There’s a certain itch while I’m reading, because there’s something here. I can really see something here and that’s what I liked about it. It’s like when Socrates was asked, ‘What is the role of the philosopher?’ and he said it was ‘The gadfly for humanity’ in that it buzzes and pokes at them to annoy them, to make them think; that’s what this book is.

Tabatha: There hasn’t been books like that in a very long time, even the ones that are similarly thought-provoking. It’s been a long time, maybe 15 years, since I’ve really read something that inspired [me], that’s in this kind of vein of really wanting to get to the bottom and questioning human beings and their actions.

Jason: I find it quite easy to understand and really engaging, actually. I really like the book.

Bart: It’s good. I want to read more. I want to read more.

Please note, unless stated otherwise, the following discussions occurred after the focus group members had read chapter 2 of FREEDOM, but before they had heard the introductory talk by Jeremy and re-read chapter 2 and read chapter 3.

Tabatha

Tabatha: I’m actually kind of shocked by how, it’s like synchronicity, I feel like this is the kind of, the last few years especially, I’ve been really losing faith in people and humanity and it’s something that I’m personally struggling with. So to read this [makes me realise] I’m not the only one. I just feel a bit more validated; it’s okay to be confused.

Jeremy: Disenchanted with the world. Okay. Confused is a bloody good word. And did you get kind of bogged down and found it too difficult to keep going?

Tabatha: No, I definitely wanted to keep going and see this different kind of mirroring, you know, philosophers and artists through history, this has obviously been a human question that people ask but, sort of, within themselves, not really a public sort of thing.

Jeremy: Good description: ‘people ask within themselves’.

Tabatha: I don’t know if I’m making sense. Those doubts that people have but aren’t comfortable in sharing them. We feel like we have to feel like we know everything.

Jeremy: Good comment: ‘We have to feel like we know everything’. Yeah, so you found it reasonably accessible reading it?

Tabatha: There hasn’t been books like that in a very long time, even the ones that are similarly thought-provoking. It’s been a long time, maybe 15 years, since I’ve really read something that inspired, that’s in this kind of vein of really wanting to get to the bottom and questioning human beings and their actions.

Jeremy: [Questioning] what’s going on.

Tabatha: Yeah, yeah. It’s a good topic, you know. The world the way it is, I think more and more people need to reflect and not just go through life blindly.

Jeremy: You’re doing well.

Tabatha: I’m sorry, it’s a bit deep isn’t!

Jeremy: No, no. You’re doing wonderfully well. ‘The world the way it is, I think more and more people need to reflect.’ Nice.

Tabatha: But that’s a pressure in and of itself. People sort of steer, even people that want to [reflect], avoid it because it’s facing the unknown, it’s scary; it’s all those kind of…

Jeremy: Good on you Tabatha. Well done.

Bart

Jeremy: Did you find the subject interesting?

Bart: Definitely, yeah. Especially when he [the author] was talking about when you were an adolescent, I experienced it myself when I was 16–17 years old. Yeah, it’s pretty interesting to read from someone who’s definitely an expert in it.

Jeremy: Coming back [after having listened to Jeremy’s introductory talk and read chapter 3], what’s your feedback, what’s your thoughts?

Bart: I think when you’re going to sell the book make sure that you put a little DVD of this recording [of the introductory talk] from last Tuesday in it. It helps, it helped me, it definitely helped me. English is not my native language so some parts I was struggling with.

Jeremy: You’re Dutch, aren’t you?

Bart: I’m Dutch, yes. So your lecture, I thought it was a really good lecture, it helped me and I started reading it again and it was like, ‘Yeah, okay, you’re in denial’ [Video/F. Essay 10 explains why humans have had to live in denial of the human condition, and the resulting ‘deaf effect’]. It makes more sense, especially when I read chapter 3 after that with the bird [referring to the Adam Stork analogy]. Yeah it’s good. I want to read more. I want to read more.

Richard

Richard: [After having listened to Jeremy’s introductory talk and read chapter 3] Whereas my first reading, I was quite, in many respects, repelled by it because not only was it confronting but I didn’t understand how the material put together, whether all the references were relevant, and I think I used the language before that I thought they appeared selective. On a second reading, it became much clearer. I could see the coordination, I could see the logic between [the references], and I felt, perhaps, much more comfortable with the context even though the concept itself was still very challenging.

It’s certainly confrontational. It’s material and ideas that I’ve not come across before, I’ll be honest, and it’s leading one to take a view of the world quite contrary to the one that I spent 50-odd years growing up with so I’m not embarrassed that I’m saying that I don’t fully understand it still, and I’m not fully comfortable with it but I am very comfortable with the idea that it’s a very interesting read and one which is prompting me to explore some dark corners inside myself and from that point of view, that’s what I would call a good book because it’s challenged me in the right places. It’s a huge intellectual challenge and from that point of view very, very interesting to try to get to grips with it.

Anna

Jeremy: So what’s your background? What are you trained in?

Anna: I am a headhunter. I have a communications and law degree, but I am not a practicing lawyer at this point.

Jeremy: So, why did you not practice law?

Anna: I did practice for a couple of years and it just drove me crazy. I was in corporate law and it wasn’t what I wanted to do.

[After having listened to Jeremy’s introductory talk and read chapter 3] To be honest, I really needed chapter 3, after re-reading chapter 2, as a bit of a soother because I think I’d obviously absorbed more than I had the first time that I’d read it and, you know, felt that I was almost descending into that depression which is discussed. So I’m very pleased that I read chapter 3. Thank you for providing that. I wondered what I’m supposed to do with this now and I feel that I need to sit with that question for a period of time before I would know the answer to that and I think that things are happening. I did the second reading yesterday and today there was a situation at work which I think I did respond to differently to how I may have a week ago and then I got all confused about my response basically. So I think I need to sit with it as it is, let things happen subconsciously and then perhaps read it a third, or maybe, even a fourth time before I’ll be able to comfortably read it.

Well, it’s partially self-preservation I think that I just don’t know what to do with it.

Jeremy: Well, you said perhaps you might have been reading it more superficially the first time.

Anna: Yeah.

Jeremy: Because if I immersed myself in what you’ve said there, you said, ‘So I started reading it after our meeting and I’m reading it more slowly and more deeply, so much so, in fact, that I’ve started to get depressed, it’s getting too close to the bone, sort of thing. Thank Goodness I got into chapter 3, which has the redeeming explanation at the end of it, to dig me out of the hole again’.

But in terms of what I was hoping for was that you would be able to go deeper with it because that’s what people do—they read it and the mind doesn’t allow them to go in there and they’re not aware that that’s happening, so they’re just skimming it. They’re getting bits out of it, they say, ‘Look, it’s a very interesting topic, it’s very meaningful, I should think about it sort of more and more’, but from the experience I’ve got I know that they’re not be really allowing their mind to be immersed in it.

So that will happen [you will start to go deeper and initially feel a bit depressed] if what I’m saying is true about getting familiarised with this forbidden realm. So that when you read it again you’re going to go very deep because you’ve suddenly had the ‘deaf effect’ eroded enough to start hearing what’s really being said and then that will get very scary.

Anna: Mmm.

Jeremy: So I would argue that it’s actually evidence that having the introductory talk did help you penetrate this stuff.

Anna: Yeah.

Jeremy: So much so that you’re seeing too much too quickly.

Anna: Possibly, yeah.

Jeremy: And you’re needing chapter 3 to bail you out of that depth, that nosedive.

Anna: Yes.

Jeremy: As to how to cope with it over time, obviously that’s the digestion process, so what are you supposed to do with this? Imagine when humans couldn’t explain lightning, how terrified were they? They must’ve thought they’d done something wrong that day and that the gods were trying to zap them! We forget just how much knowledge we have now and how hard it would’ve been to have a fully conscious mind living on this planet without any answers. I mean, the sun goes up and comes down, but then early humans would have been terrified that it’s not going to come back tomorrow morning, they really would’ve been! They sacrificed their kids and did terrible things because of their ignorance. It must have been so mysterious to be awake, thinking, but without any answers, it’s a terrifying affliction.

So we’ve accumulated a lot of knowledge now, but what happens with knowledge is that it takes time to filter through the absorption system. But already you said, ‘I’ve managed to go deeper, I’ve been watching my behaviour’. It was making everything clearer, so that’s what it’s supposed to do for you—it’s giving you greater understanding and peace of mind because you can make sense of experience.

So that’s what the book does, it transforms humans by bringing them understanding that makes sense of their world at last. The key passage in J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (in fact, it provides the meaning behind the book’s enigmatic title), is when Holden Caulfield says: ‘I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff—I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be’ (p. 156 of 192). So instead of being troubled and bewildered and confused, the time that Holden so yearned for when we will be able to ‘catch’ all children before ‘they start to go over the [excruciating] cliff’ of Resignation has finally come about [read more about Resignation and The Catcher in the Rye in F. Essay 30]. The real ‘catcher in the rye’ is the ability to explain the human condition and that would allow children to keep thinking and keep making sense of the world and not have to resort to mysticism or superstition or sacrificing their kids or the horrors that have gone on out of sheer ignorance. We need brain food not brain anaesthetic; we want answers and if you get them in this critical interface of the human condition, they’re massive, they’re going to ‘trickle-down’ and make sense of everything. There’s going to be a huge amount of digestion so you’ve got to be patient. At that point you’ve got to back off a little bit, just put it on the back burners, exactly as you said, leave it to filter through gradually and it should help you make sense of things. That’s the benefit of it, that’s what we’ve always wanted, we’ve wanted something to makes sense of all the madness and confusion. But this is based on love. It’s a compassionate understanding, which is what you discovered in chapter 3.

Anna: Yes.

Jeremy: You’re saying, ‘Gee whiz Jeremy, in chapter 2 you just bury me deeper into this hole, getting darker and darker, and in chapter 3 you bail me out. I’ve been thrown around like a rag doll, you know; good cop, bad cop—he comes in and belts the living daylights out of me, then gives me a big hug and says I’m a goody goody and I don’t know whether I’m coming or going at this point!’

Anna: Mmm!

Jeremy: But anyway that’s just wonderful Anna, so thank you for that.

Anna: Yeah, look, thank you actually. I’m not saying I agree with absolutely everything but who would say that.

Jeremy: Especially at this early stage.

Anna: Yes, but I feel that I’ve been presented with another perspective and I’m not at a stage yet where I can accept it in its entirety.

Jeremy: You shouldn’t.

Anna: But it’s definitely making me think and I will continue to do so I think.

Jeremy: And the next generation coming, very soon [Anna was pregnant at the time].

Anna: Yes, I did think that actually.

Jeremy: Hopefully, will come into a more tranquil, more self-understood and peaceful world. And it actually should help you.

Anna: Parenting, yes, definitely. I tried to talk to my husband about it and he got very confused so he wanted to read it himself.

Craig

Jeremy: [After having listened to Jeremy’s introductory talk and read chapter 3] So, Craig, thanks for coming back and obviously we’re interested in your feedback and you’ve done your homework, I see, which is wonderful.

Craig: I have, I have.

Jeremy: So, what are your thoughts?

Craig: So, it [chapter 2] was easier on the second read through, like you said. I don’t know if that is just because I’ve already read the content or… I don’t know, it just felt easier to read, maybe I got used to your style with all your different things in it [referring to the use of bold quotes and quote references throughout the text etc.]. Basically, what I still have a problem with is that you say that there are universally accepted ideals of life and that is being cooperative, loving and selfless, but I don’t know why you say that these are universal. I mean, yeah, they’re good attributes but what makes them universally accepted ideals of life?

Jeremy: Yes, well, that is what chapter 5 is all about.

Craig: Right.

Jeremy: Okay, so you guys were only looking at chapters 2 and 3, but there is this question that has bewildered and troubled biologists, one of the big questions about the origins of consciousness [see F. Essay 24]. Understanding the human condition is the most important question to solve [see Video/F. Essay 3], but the other great mystery has been the origins of our moral nature [see F. Essay 21]. So humans do have a moral nature, sure they’ve got a propensity for enormous acts of violence and atrocities but there’s also a very sensitive, compassionate, loving side to humans and it’s instinctive, we’re born with it. It’s what we call our conscience.

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: So, in biology, as I talked to you about during my introductory talk, every second article in the science journals has the latest theory on the origin of our moral nature.

Craig: Right.

Jeremy: So it is an accepted universal thing and so how could we have acquired that biologically since genes are selfish and will only foster selfishness? How could a selfish system, namely genetics, which only fosters selfishness—because someone who’s unconditionally selfless will presumably go and give their life for others and will not pass on their genes because that trait would disappear—produce an unconditionally selfless, altruistic nature, how could that possibly emerge in the human make-up?

So there are all these theories to try and explain that and that’s what the latter part of chapter 2 talks about: Social Darwinism, Evolutionary Psychology and so on [see also Video/F. Essay 14]. There was a big flaw with Social Darwinism, the contrived excuse that ‘nature is selfish and that’s why we are’ because it didn’t account for instances in nature where selflessness does occur. And then Evolutionary Psychology, which says we’re just trying to foster the genes of others to reproduce our own genes indirectly, we’re not being selfless, we’re actually being selfish, was also flawed. If you look at ant and bee colonies where workers slave selflessly for the whole colony, like when a bee stings you, it dies.

Craig: Right.

Jeremy: So it’s giving its life. But Evolutionary Psychology explains, truthfully enough, that what the ants and bees are doing in their unconditionally selfless behaviour is actually fostering their own genes by looking after the queen that reproduces them. She is the breeder.

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: So, actually they are still being selfish, they’re still meeting the requirements of the genes to be selfish, right?

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: So, what they did then was they pulled the trick that says, this explains our altruistic nature too, that all we’re doing is being indirectly selfish, it’s a subtle form of selfishness. When we’re being kind to somebody, we’re just trying to make sure that our genes reproduce because they are related to us, as happens in an ant or bee colony, which is patently untrue because it doesn’t account for acts of selflessness towards those who aren’t related to us.

Craig: What about feeling good? What about altruistic behaviour because it feels good?

Jeremy: That is what we would say would be our conscience. We could all work out rationally that ideally it would be better if everyone was cooperative, loving and selfless. That is a fairly obvious ideal and so you could say we’ve got a conscience, a moral self just from rationally looking at the ideal situation which would be everyone being cooperative and loving. Like communism which says we should share everything. But it’s universally accepted that we’ve got an altruistic moral nature, an instinct which our conscience is the voice of, the expression of within us. So we are born with this instinctive propensity to be selfless, like the example I gave in FREEDOM, par. 380, of the professional footballer Joe Delaney who admitted that ‘I can’t swim good, but I’ve got to save those kids’, just moments before plunging into a Louisiana pond and drowning in an attempt to rescue three boys (‘Sometimes The Good Die Young’, Sports Illustrated, 7 Nov. 1983).

So, yeah, it is universally accepted that we’ve got this moral nature but how did we acquire it? That’s the great mystery, because all these biological theories are actually human-condition-avoiding theories. That’s why chapter 3 is so important because it presents the explanation of how we acquired our altruistic moral instincts without using a human-condition-avoiding explanation. That’s what I was trying to explain in my talk to you, that once you understand that humans are living in fear of the human condition, in this metaphorical cave of denial [see Video/F. Essay 11 for an explanation of Plato’s cave allegory], you can see why scientists developed all these theories that want to avoid the human condition, not confront it. They are dishonest theories, and I just gave you an example of Evolutionary Psychology which says that bees give their life because they’re fostering their own reproduction by fostering the queen.

Craig: Yep.

Jeremy: But then to extrapolate that and say that when we behave selflessly towards others, like the footballer who gave his life trying to save those kids, we’re trying to foster our genes in those that are related to us, doesn’t make sense because in that example, those kids obviously weren’t related to him. They would say that’s just an aberration of the basic idea but obviously there is a huge flaw in that argument. So what happened then, as you’ll read in chapter 2, is that they switched to another shonky theory which E.O. Wilson had come up with, saying, ‘We’ve used that Evolutionary Psychology lie long enough, it isn’t working, let’s find another one’. The Multilevel Selection theory for eusociality is even cleverer but it is still avoiding the human condition [again, see Video/F. Essay 14].

So if you go to chapter 5, supposedly it will explain the real reason for how we acquired our moral nature in a human-condition-confronting, truthful manner and that is the thesis of the whole book: to establish that humans are living in denial and can’t face the truth of the human condition so everything they are saying and all their theories are human-condition-avoiding, right?

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: And then it goes through and looks at all these big questions and, by not avoiding the human condition, makes sense of them.

So, what happens when you get to chapter 5? It answers this massive question: How did we acquire our unconditionally selfless moral nature, that our conscience is the expression of, that we’re all born with? And the answer is through nurturing, and the bonobos provide us with a living example of this occurring [see F. Essay 21].

Craig: Right.

Jeremy: Now the reason this nurturing explanation has been human-condition-avoided and never been admitted, well, it was actually put forward as a developed theory by the philosopher John Fiske in his 1874 book, Outlines of Cosmic Philosophy: based on the Doctrine of Evolution about three years after Darwin’s work was published and it was actually described as a theory far more important than Darwin’s principal of natural selection (see par. 488 of FREEDOM). But Fiske’s theory was left to die due to our fear of the human condition, because if it’s true that nurturing made us human, and that nurturing is, therefore, the most important ingredient in what is making us human and our growing up and our development from infancy to adulthood; it confronts parents with their present inability to nurture their children as much as they were nurtured before the human condition emerged. So as I say in FREEDOM, parents would rather admit to being an axe-murderer than a bad parent.

Craig: Right.

Jeremy: So it’s an unbearable truth. First, we need to explain the human condition, the good reason for our upset corruption and then we can safely admit all these other truths. So chapter 3 explains the human condition, so now that we’re defended I can go and talk about nurturing being the prime mover in human development and in our individual lives because it’s at last safe to do so. We can now explain why all mothers and fathers are variously alienated and certainly when children come into the world they are hurt by that falseness. Parents do their best but they can’t hide their alienation from their children so children can see it and are very hurt by that. [See chapter 8:16C of FREEDOM: ‘The dire consequences of terminal levels of alienation destroying our ability to nurture our children’.]

Craig: What about morals as an invention of the rational mind as opposed to something intrinsic?

Jeremy: Well, as I said a little while ago, we can work out rationally that if a group of people cooperate they do a lot better. If everyone is loving, selfless, cooperative and considerate of others it will be a much more efficient system. So you can work it out rationally that there is a moral ideal, and that’s apparent even without a conscience, just from logical observation that things work better if everyone is selfless and cooperative. That’s the human condition—why aren’t we like that? As I talk about in FREEDOM there are three ways we can work it out: one is through understanding our instinctive conscience; two, from observing that selflessness is a more efficient way to cooperate and; three, because we recognise this integrative theme of existence, the development of order of matter, which is explained in chapter 4. So we can work it out from three directions that selflessness is better than selfishness, if you like.

Craig: But I’m not trying to say that selflessness isn’t better than selfishness, what I’m trying to say is, don’t you think morals might exist because of the societal pressure?

Jeremy: Yes.

Craig: Like, people want to live with people they can trust, that they can get along with, so that comes from a societal thing rather than, because I noticed in your book, you quote Rousseau when he says…

Jeremy: ‘nothing is more gentle than man in his primitive state’ (The Origin of Inequality, 1755; The Social Contract and Discourses, tr. G. Cole, 1913, p.198 of 269).

Craig: But what about the other philosophers, like Thomas Hobbes [‘His understanding of humans as being matter and motion, obeying the same physical laws as other matter and motion, remains influential; and his account of human nature as self-interested cooperation, and of political communities as being based upon a “social contract” remains one of the major topics of political philosophy.’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hobbes)], who says man is just a primitive savage who just follows his own, basically, utility maximizing: ‘I do what I want because it feels good’, what about that?

Jeremy: And, ‘because I’m trying to reproduce my genes, I’ve got to defend my territory and my family’—that’s what the latter part of chapter 2 deals with, all these reasons that we have used to deny this condemning truth that Rousseau admits to. You will see in chapter 2:10 where I explain Evolutionary Psychology, that E.O. Wilson, its main proponent, said that, ‘Morality has no other demonstrable function’ other than to ensure ‘human genetic material…will be kept intact’ (On Human Nature, 1978, p.167 of 260); even saying that ‘Rousseau claimed [that humanity] was originally a race of noble savages in a peaceful state of nature, who were later corrupted…[but what] Rousseau invented [was] a stunningly inaccurate form of anthropology’ (Consilience, 1998, p.37 of 374)!!

Craig: Yes, I saw that quote.

Jeremy: So again we’re talking about the human condition here because humans don’t want to admit that truth about our altruistic moral instincts because it’s so condemning, so they’re trying to find ways of escaping the condemning truth. So if a society gets too idealistic—say, by imposing socialism, that everyone should share and be cooperative—and we’re all sufferers of the human condition—aggressive, angry and competitive, the opposite of social—it falls apart because it’s too unrealistic, there’s too much social expectation on everyone being loving and cooperative without any recognition of the human condition. That’s why chapter 3 of FREEDOM is so good because it explains why we had to become selfish and aggressive, but in the cause of searching for knowledge. Chapter 3 provides the defence for our corrupted state and why socialism, along with other idealistic movements, was a false start to a utopian world because we hadn’t solved the human condition yet. We can’t fly back on course and be ideal until we’ve been understood. [See Video/F. Essay 14 and F. Essays 34 and 35 on why left wing philosophies represent a false start to a human condition reconciled world.]

Craig: You also say, with regard to the human condition, it comes about because what our instincts want to do goes against what our rational mind wants to do.

Jeremy: Yes.

Craig: Why do you think that is?

Jeremy: Okay, we’re looking for the explanation for the human condition, right? The thesis is, as I talk about in the latter part of chapter 2, that all the biological theories that have been put forward don’t cut it, they don’t genuinely explain it, they are actually trying to avoid the human condition not confront it, and what I also say is that if we look at the human condition truthfully, all these questions are very simple to answer. Let’s look at the first problem which is the biggest of all, the human condition itself. How do we explain that? To answer your question I begin, in chapter 3, with a quote from naturalist Eugène Marais who recognised that ‘As the…individual memory slowly emerges [in humans], the instinctive soul becomes just as slowly submerged…For a time it is almost as though there were a struggle between the two.’ (The Soul of the Ape, written between 1916–1936 and published posthumously in 1969, pp.77–79 of 171) The great philosopher, Nikolai Berdyaev was also approaching the truth when he wrote that ‘The human soul is divided, an agonizing conflict between opposing elements is going on in it…the distinction between the conscious and the subconscious mind is fundamental for the new psychology.’ (The Destiny of Man, 1931, tr. N. Duddington, 1960, pp.67–68 of 310) [See Video/F. Essay 4 for further evidence from history’s thinkers that the ‘instinct vs intellect’ is the obvious and real explanation of our condition.]

Craig: But I’m saying, why? Why do you think there is a clash between what our instincts are and what our mind is thinking?

Jeremy: Well, we’re trying to explain the human condition, that’s the destiny of the exercise right?

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: So we are trying to find some explanation that would make sense of that right?

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: That there would be this clash, so all I’m saying is that anybody thinking truthfully about it would recognise, as the first step of the argument, that when we became conscious, that being an insightful learning system, there had to be a clash with the already established orientating learning system, which is genetics. So there in is the roots of the explanation because if we think enough about that, it would produce the human condition. It would explain why we behave the way we do. If you look at chapter 8 of FREEDOM, it goes through and interprets the whole of human development from the time we were apes. Using that explanation, of the difference between the gene-based and the nerve-based learning system, everything starts to fall out, everything starts to make sense. Like in our talk earlier, we were talking about children and how, as they started to encounter the human condition, they become more and more frustrated and they start thinking about it more and more. That’s all based on some awareness that there is this problem, something going off the rails. If you interpret human behaviour using that explanation, it will make sense, and the fact that it makes sense is the evidence that it works, that it’s truthful. You can actually remember the day, the moment, the page number when finally realise that the Adam Stork story I told you about earlier [in chapter 3 of FREEDOM] really does explain the human condition because you can experience the truth of it, it really does make sense; and the more you look down into it if you’re really stridently cynical, which everyone should be, ideally, the more it will make sense.

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: And you’re good on that. You’re really good on that.

Craig: Right.

Jeremy: No, no, you are.

Craig: Yep.

Jeremy: You should be and you’re not going to be bulldozed, you’re a very rational bloke. So you want to know exactly, how do you know that it’s true? What is presented in chapter 3 is the explanation, but the more you study it and look into it, the more true it would be that a clash had to occur and the nature of that clash. I mean, even if you go right back into the mythologies, like Genesis in the Christian mythology, and Genesis is the basis of Judaism, Islam and Christianity. Genesis says we were living in the Garden of Eden which is the innocent, pre-human-condition state, then we took the fruit from the tree of knowledge, became conscious and then the shit hit the fan, so it has all the elements there and now we can explain the preconscious state, which is the gene-based orientating system.

Craig: Yep.

Jeremy: And we can explain that we became conscious. Already there is a recognition there. So that’s what Moses wrote down in 2000 B.C., a long time ago, it’s an obvious truth that these two factions exist in us [again, see Video/F. Essay 4 for other thinkers who have recognised the basic elements involved in creating the human condition].

Craig: So are you saying, as a practical example to that, if we were hungry and someone else has food that our genes would tell us to steal and our rational mind would feel bad about it, is that what you’re saying?

Jeremy: No, no, it’s the opposite. I’m saying, using the Adam Stork story, birds are instinctively orientated and that’s how they know where to fly and where not to fly?

Craig: Yeah, yeah.

Jeremy: But obviously we’re not birds. So our orientation wasn’t to a flight path. Our orientation, as is explained in chapter 5, is that we were once nurtured to acquire this unconditionally selfless, loving soul, that’s our instinctive self. So I’m saying, our instinctive self was to being cooperative, loving and selfless, right?

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: Okay, but it wouldn’t matter what sort of instinct you had. If you then become conscious, there’s going to be a clash between the instinctive way of learning that just wants you to behave obediently to these orientations, they’re not understandings, and the intellect or nerve-based learning system that needs to experiment in understanding and do things differently. A chook sits on her eggs for 28 days or however long it is because she’s instinctively selected to do that. But if the chook starts to think for herself, get off her eggs and carry out all these experiments, mayhem breaks out. But in our case, it was so much worse, It’s called the ‘double and triple whammy’ [see chapter 3:5 of FREEDOM].

Craig: Yeah, I’m just reading about that.

Jeremy: The double whammy is just that. In our case when we began searching for knowledge and became angry, egocentric and alienated, that response was extremely offensive to our particular instinctive orientation because our instinctive orientation isn’t to a flight path, or to any of the various instinctive orientations that other animals are obedient to; it is to behaving in the opposite way, namely lovingly, selflessly and honestly and cooperatively. So in our case, when we began experimenting in understanding and were criticised by our instincts and unavoidably responded in an angry, egocentric and alienated way, we had to endure a further round of criticism, a second hit, a ‘double whammy’, from our instinctive orientation. So it got really bad for us. And there’s a third whammy as well, which is explained in par. 263 [of FREEDOM], because we’re also defying integrative meaning [see F. Essay 23 on the integrative meaning of existence].

Craig: How is our conscience separate from our rational mind though? How can our conscience not like what our rational mind does? How do they develop as separate things?

Jeremy: Okay, well, you have instincts that make you want to go to the toilet or want to eat food.

Craig: Yeah, yeah.

Jeremy: You can consciously override that and say, I’m not going to go to the toilet now, or, I’m not going to go and get a feed now, you can override your instincts. We’ve got instincts that want us to behave cooperatively, lovingly and selflessly, but our conscious mind can defy those instinct, we do it all the time. So, yeah, our instincts ‘in effect’ criticised us. I always use the phrase ‘in effect’ because that’s not literally what happened, they just want us to, in effect, behave in a certain way, but when we’re conscious and self-adjusting, we often end up doing things a different way and at that point the instincts are ‘distressed’, if you like, and ‘in effect’ they criticise our conscious brain because they don’t want that to happen.

Storks are perfectly oriented to fly around Africa and their instinct take them around the north western ‘hook’. If they try to fly east across the Sahara their instincts are going to pull them back on course. Instincts are really powerful and can influence us and make us want to do things. But if we then become sufficiently conscious we’re able to wrest management of our lives from the instincts, take over control.

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: For a long time our instincts will still be in control and fully dominant, they’re going to be so powerful, so well entrenched but eventually if we become sufficiently conscious and able to understand cause and effect, then we’re going to challenge that control, and then we’re going to get ourselves into trouble, because we’re going to be at odds with our instincts.

So our instincts were to being cooperative and loving and now we’re getting aggressive and competitive, so we’re really in big, big trouble, and that’s why I say, if you really immerse yourself in that, where are these volcanic forces within us coming from? Sure, we are civilised and we try to restrain it but there are huge volcanic forces in humans, real, deep anger that is coming from somewhere. Capacity for extreme acts of violence and brutality and torture, really bad psychosis coming from somewhere. If you immerse yourself in that little struggle between those two factions and that we’ve been unfairly condemned and can’t explain why, we’re going to get really upset, really, and it’s a double and triple whammy because we are getting doubly and triply condemned.

So now old Adam Stork is absolutely furious, because we’re not storks, our instinctive orientation is to behaving cooperatively and lovingly and suddenly we become monsters. The burden of guilt is going to become astronomical, no wonder we are furious inside and it comes out in war and so on and people torture each other. There is horrifically volcanic anger within us. The more you immerse yourself in that theory and walk around with it, the experience has been that it becomes more and more accountable, and when it clicks and starts to make sense of what you’re looking at everywhere, it’s really powerful.

So it is a fair bit to get your head around and takes a bit of reading and you need to remain objective and keep questioning.

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: And you can send me an email anytime and I’ll try and help you, but just read and keep reading it and reserve your judgment as you should, and you’ll definitely do that because you’re very rigorous which is wonderful, until it does start to make sense of things. Either it will grow in its accountability or it won’t. So you’re on safe ground, especially if you’re a very rational person like you are, so that’s the best that I can explain it.

Craig: Okay, let’s just say, I finish the book—and I plan to finish it because it seems unfair to make a judgment without reading it in its entirety—and I don’t believe in it, doesn’t that mean that I have to admit to myself that I’m in denial? That I’m incapable of seeing the truth?

Jeremy: No, no, no. That is what you were raising the other day. It’s called the ‘non-falsifiable principle’. There are certain situations like Freud’s ‘penis envy’ where if you say that you haven’t got it, that’s an indication that you have.

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: Now look, I didn’t create the dilemma of the human condition which creates this state of denial and alienation, so it has this aspect but I didn’t create it. It’s not a deliberate attempt by me to be devious.

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: And secondly, very importantly, these theories are testable. You can validate them or disprove them. So you’re on safe ground. Yes, superficially it’s a circular argument and you get condemned as being alienated but you’re on safe turf because you can keep thinking about it and try and find the holes in it and if there are serious holes you should sweat on them until they either validate themselves or they don’t. But you should keep in mind that the theory is that humans are deeply alienated and that there is this historic fear. So you do have to be very judgmental about this because these are frightful frontiers. Dr David Chivers at Cambridge loves my work and there’s a video of us talking.

Craig: On the website?

Jeremy: Yeah, and he said, ‘Jeremy, I’m running with everything but one thing I really can’t cope with, I need some help with, I’m not persuaded by is that autism is caused by lack of mother’s love and hasn’t got a genetic basis’, so I went to great lengths to try and explain that you’ve got to expect that after two million years humans are going to be horrifically upset and no mother is going to be sound and secure enough to give their child the amount of love their instincts expect [again, see chapter 8:16C: The dire consequences of terminal levels of alienation destroying our ability to nurture our children; see also F. Essay 55 on the endgame state that the human race has now arrived at]. Dr Chivers said ‘I think all parents genuinely want to be good parents’, and I agree. It’s not that, it’s that we’ve been two million years alienated and children come into the world still expecting us to be innocent and free of the human condition and we’re not and so of course they die a million deaths. But it’s not a lack of love in the sense of intended love, it’s just that we’re all alienated and kids can see the difference. That’s the significance of Resignation [again, see F. Essay 30], kids can see through the falseness but, unable to understand it, eventually they have to resign themselves to it.

So that’s a sticking point for Dr Chivers and he says, ‘Well, have a crack at that, Jeremy, and see if you can persuade me,’ and you’ll hear at the end of the conversation, he smiles and says, ‘Maybe I need to go and reflect on this’, which is good, I’m cool with that and he’s got to think about it and see if it doesn’t gel in his mind after a time, that this really does make sense of those things.

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: You also have to consider that humans have got this resistance to wanting to be honest about this part of themselves, so you’re going to have to be fiercely objective because it could be because you’re trying to block a truth.

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: It’s just amazing how powerful this denial is when it gets going and it can really be determined to not accept a truth.

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: Because our minds have learnt that the consequence of allowing this truth through is fearful depression and that’s the hard thing to differentiate.

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: You’ve got the woman who decided not to even participate in the focus group because she said, ‘The book is absolutely terrible, it’s incomprehensible and I’m very angry about it, I’m not coming to the meeting.’ Alright?

Craig: Yep.

Jeremy: And then a completely counter example would be the woman who wrote a review for Executive Woman’s Report magazine in which she said, ‘Was Jeremy Griffith struck by lightning on the road to Damascus…Such was my cynicism reading the summary…Then whack! Wham! Reading on I was increasingly impressed and then converted by his erudite explanation for society’s competitive and self-destructive behaviour. His is not a band-aid cure for mankind’s sickness but a profound thinking through to the biological cause of the illness.’ [See Reviews and Commendations for Beyond the Human Condition and Free.] So she just loved it.

Craig: Yeah.

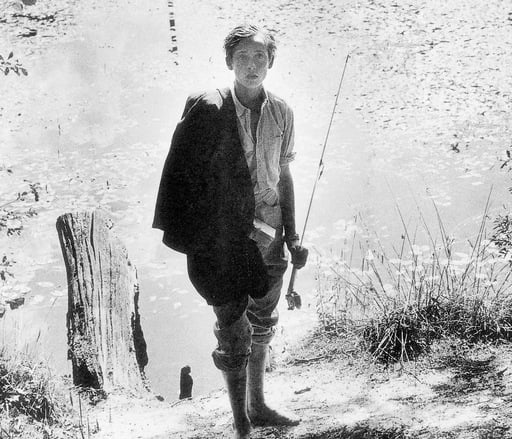

Jeremy: Not only that, she said that she read it all in one night. So she had no trouble and it went straight through. So I wrote to her and asked her how she was able to read it so easily because for most resigned adults it’s a struggle, and this is what she wrote back: ‘Our 12 year old son was killed in a bicycle accident eight years ago and God literally hammered on my soul and senses. Miracles, signs, phenomena were granted me because I kept open the communication lines and begged God to help me.’ Because she was absolutely desperate she could take it in. We call it ‘shattered defence’ when, at a certain point of despair, all the blocks and denials become meaningless and pointless. It’s like the photograph in FREEDOM of the boy who had, the previous day, lost all his classmates in a plane crash—you can see in his expression that all the artificialities of human life have been rendered meaningless and ineffectual by the horror of losing all his friends (see par. 115 of FREEDOM). As she said, ‘I kept open the communication lines’ so she could hear it all.

‘Too poor to go on school trip, boy fishes the day after classmates perish in plane crash’

LIFE magazine, Fall Special Edition, 1991

So one person says the book is terrible, incomprehensible, totally impenetrable and I’m very angry about it and the other says she loves it. So something funny’s going on, they are polar opposite views. So you have to immerse yourself in it and work your way through it by all means. What normally happens with people who are fair-minded is they go through the book but they’re still holding a lot of reservations, like Dr Chivers, and that’s fine, he should be rigorous about it. But that’s the response: Jeremy is getting in behind the human condition, that’s not a bad effort, there’s a lot of things that are making sense so his track record is growing. But at a certain point you might say, but I disagree that autism is caused by a lack of mother’s love. And Dr Chivers is hung up on that and good on him and he said he’d take it on notice so let’s see if it doesn’t start to make sense.

At the end of the day, I’m suggesting that what will happen is that this whole thing will boil down in your mind to a wrestling match between whether humans want to come clean or whether they want to stay in denial forever. Do you want to just stay living in denial because confronting the truth is too frightening, even though we now know the truth defends us?

Craig: Yeah.

Jeremy: That is why it’s historically been called ‘Judgment Day’. You can read about it in chapter 9:3 [and in F. Essay 40], this is ‘shake-down day’, ‘draw-the-blinds day’, ‘come-clean day’, it’s a terrifying time, it’s the biggest paradigm shift the human race has ever had to face and there’s going to be a lot of resistance. Very deep and angry resistance. Well, as Plato said, ‘And if he were forcibly dragged up the steep and rocky ascent [out of the cave of denial by the person who has broken free of the cave] and not let go till he had been dragged out into the sunlight [shown the truthful all-liberating—but at the same time all-exposing and confronting—explanation of our human condition], the process would be a painful one, to which he would much object, and when he emerged into the light his eyes would be so overwhelmed by the brightness of it that he wouldn’t be able to see a single one of the things he was now told were real’. And he didn’t stop there, going on to say, ‘And if anyone tried to release them and lead them up, they would kill him if they could lay hands on him’ (see ch. 1:4 of FREEDOM). That’s how angry they will be that the blinds are being drawn on their world. Everyone is very comfortable living in their cave of denial with their theories and beliefs. Of course, what they will eventually realise is that it’s not a day of judgment but a day of compassion and understanding.

So anyway, you’ve just got to keep reading it, chuck it over your shoulder the moment you think it’s full of shit but if it’s not, do the opposite, that’s all I’m saying.

Craig: Okay. So I’ve just got two questions and a comment to go.

Jeremy: Okay.

Craig: So, why do people do good things, moral things now, do you think that’s their instincts overriding their mind?

Jeremy: I might answer that with the rest of the group.

Craig: Okay, yep sure, pass that one. How were you able to think of this?

Jeremy: Okay good one, I will answer that with the group too, what’s your last one?

Craig: The last one’s a comment and I’m just saying for the book, for your benefit, maybe you should ask people to read it a few pages at a time. Maybe you should ask them that in the book if they can just read it extra, extra slowly because as you said they’re going to be initially, and I think it’s true with me as well. I was initially more sceptical than I was on a reread, maybe if you can get them to read one or two or three pages at a time, think on it, come back tomorrow. If you could put that at the very front.

Jeremy: That’s really good, what I’ve got in there, what we’re adding to it is to be patient. The two tools were to watch the videos and be patient as all get out [see Video/F. Essay 11: The difficulty of reading FREEDOM and the solution].

Nancy

Nancy: Well at first I was a bit like, ‘Oh my god, I’m just a regular person, how am I supposed to read this?’ But as I’m kind of getting through it I actually realise that it’s not as complicated as it seems. I actually relate to what is being said and it really made me think of what I was studying and how I felt when I was younger, you know, you talk about adolescence a lot and how I was feeling. And how I’m feeling right now as well, because I’m a person who can be really frustrated in life, with other people, and can be a bit antisocial and it made me think, why am I like this? Maybe this is actually an explanation of all the things that I’ve been feeling. So it actually really interested me and as I was getting through it I wanted to know more and more and I’m quite looking forward to reading chapter 3 and getting the answers to this big introduction. So, yes, I understand that this is something we really need to consider and I want to know more.

Some paragraphs, I felt like I was reading it and then at the end I was like, ‘What, wait a minute’, I just had to reread it. But sometimes I actually chose to reread because I felt like it was a really important bit or because for example, you talked about The Catcher in the Rye and that was a book that I read in high school and I really liked it and I really want to understand what I understood back then compared to what your book would compare it to and understand a new perspective, and also something that the teacher obviously never talked about.

We talked about The Catcher in the Rye for a long time and it actually struck a chord with me because I was going through adolescence reading that book and I was going to this really exclusive high school with all the ‘phonies’ and I felt like I could really relate to the character and understand what he was going through but without knowing what it was. I just assumed that it was the adolescence crisis, like everybody calls it, but what is it? Who knows? You’re just going through something so, it felt like I could understand a bit more of what happened back then and it’s quite big, I feel. Like you can understand a lot of the things you could never understand back then. Yeah, I think it’s pretty powerful. [Read about Resignation and The Catcher in the Rye in F. Essay 30.]

John

John: Initially I was pretty stimulated by it, I thought it was quite interesting. It’s been a while since I’ve read a philosophy book so it drew me back into the books I’ve read over the years, and that was the first thing I enjoyed. I liked the concepts, the good and evil argument, everything from Nietzsche and so forth. I did like it up to around page 15–16 or so of the second chapter. I was really enjoying it, all the mixing of the relatively modern references like The Catcher in the Rye, The Beatles and making it all stand out a little more to the more modern reader and I like that, that was bringing me back to base with it.

It sort of lost me a little bit towards the second half [of chapter 2] mostly because I found that the argument that was being put forward was being put forward for humanity, for the general public, whereas, it seemed to be more for the pessimistic person. For example, when they said that at the age of 14 or 15 we have this sort of realisation about the human condition. At that point I thought, I don’t really feel like I had that, I feel like that is a pessimistic view and I do know people who would experience that and not just at that age but in general but I couldn’t quite relate to it and even when it was referring back to Plato’s cave, things like that, there were certain assumptions that were made by the author and I’m not so sure, there was a little bit of A plus B equals C when I think it was too big a jump to make, basically. So he was sort of cherry picking, a little bit, of the facts but for the most part, all the way through, I felt quite stimulated by it and by the end it made you question yourself a little bit about just daily life and, you know, maybe I should make a couple of changes in my own life, so that got to be a positive thing.

Elysse

Elysse: [After having listened to Jeremy’s introductory talk and read chapter 3] Yeah, chapter 3, it makes sense. I’m not 100% sold yet but I think I need to read further chapters because I really want to [understand], mostly, the explanation of why we do have this instinct to be good people, like I know there was…

Jeremy: The instinctive what?

Elysse: The instinct to be like, that we are good, loving people.

Jeremy: Yeah, our moral nature.

Elysse: Yeah, because you did briefly talk about that in the second chapter but I would just like more background on that which I’m sure is…

Jeremy: Yeah that’s really interesting stuff, when you get to chapter 5 it’s all about bonobos and nurturing and stuff like that and being a biologist you’ll be jumping out of your skin, I think, when you get there!

Elysse: Yeah?

Jeremy: And there’s some big questions still, so you should be taking it on notice and it’s biology but you said you didn’t study any of this! You must have found it pretty fascinating.

Elysse: Yeah, I did, it is kind of disappointing that we don’t ever talk about those kinds of things.

Jeremy: Yeah, well that’s right, because it’s scary.

Elysse: Yeah.

Jeremy: It’s a core issue and we’ve never been able to make sense of it and we come up with all these false theories from living in the cave. So it is the question but, as I said, even Darwin didn’t address it.

Elysse: Yeah.

Jeremy: I mean, The Origin of Species, the most interesting species to know the origin of is ourselves, but humans aren’t addressed at all in The Origin of Species. 12 years later, Darwin made some references to human behaviour but it was still only a tentative step in that all-important exploration. The stark emission is amazing, well, it’s not amazing because the next frontier is the human condition and that is this horrifically scary subject.

Good on you Elysse.

Adrianna

Adrianna: Personally, I liked it and I didn’t find it difficult to read. Maybe because I belong to science, I don’t know, but the first pages I found, in a moment I felt like, are we talking here [about] seeing the human being like a negative thing only? Up to page six if I remember it right, but then when I started to read in further all the explanations, I actually got the figure [idea].

Jeremy: Right.

Adrianna: Yeah. Well, it’s my personal…

Jeremy: Interest.

Adrianna: Well, I thought while reading it…

Jeremy: You were in education, in agriculture?

Adrianna: Yes, I’m in agricultural environment, University of Sydney.

Jeremy: So, this subject of the human condition, have you encountered that before in any of your reading or studies?

Adrianna: As a term, yes, but that’s why at the start I thought, is this regarding only to the negative side of the human being or thinking? It seemed that I didn’t have a full understanding of it which I did find through reading the second chapter.

Jeremy: Yes, and was it interesting?

Adrianna: It was very interesting but to understand it 100% I think people have to know all the artworks you have included, which is beautiful, I like that, and [the work] you have referred to because a few of them I didn’t know so I had to research, but then you get the full picture.

[After having listened to Jeremy’s introductory talk and read chapter 3] The talk actually helped me a lot, I could reach understanding of some points that I couldn’t in the first reading I had. It did [help me], you explained it very good. I was happy, that’s why I got interfering [speaking up during the introductory talk].

I actually like it as I said. I find myself in there, so not only for my son’s case but for myself as well. I have kind of been in a bit of depression once for circumstances so I do find that yes, you’re right, that human condition is kind of forgotten and we don’t get to think of it. We just think of the cause of our problem that is something physical that happened or something spiritual in the case of losing someone, a loved one or something, that was my case. So yes, but we forget that actually it’s there, that we are human and this condition exists, we have to refer to it. That’s how I understand it.

Torin

Torin: I found parts of it very easy to read and smooth flowing, other parts I really had to labour with because some of the sentences were really quite long and complex. I mean, if you’ve got an interest in a subject and you have an interest in philosophy and know something about it then you can work your way through it and obviously what’s being offered is a new perception of an answer to this question that all of humanity has been wrestling with. So it is a profound subject that some people would have an interest in and just do the work to get through it.